|

|

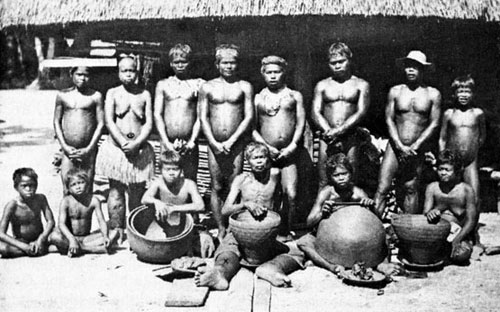

Figure 5.1. Inhabitants of Chowra and their pottery (ca. 1900). |

The Nicobar Islands

Nicobarese early history and prehistory

by Dr. Simron Jit Singh

|

Table of Contents

Early references to the Nicobar islands |

|

The following text was originally published as Chapter 5 (pp. 131-154) of Simron Jit Singh's In the Sea of Influence - a world system perspective of the Nicobar Islands, Lund Studies in Human Ecology 6, Lund University, Sweden, 2003, ISBN 91-628-5854-8, ISSN 1403-5022 Copyright ©2003 Simron Jit Singh Footnotes are marked in the text with square brackets [ ] and can be found at the end of the following paragraph. For references mentioned in the text consult the printed book. |

|

Virtually no archaeological work has been done in the Nicobar islands so far. For the possible antiquity and ancestry of the Nicobarese people see Kumarasamy Thangaraj et al Genetic affiliations of the Andaman and the Nicobar islanders I cannot let this opportunity pass to call for archaeological research in the islands, perhaps starting with the "pottery island" Chowra. George Weber |

The location of the Nicobar Islands on a prime trade route to the Far East, and in particular to the spice islands[1], I has had inevitable consequences for its inhabitants and its ecology; this more so with the beginning of the European colonisation of Asia. Even before the arrival of the Europeans, Asian seas were the scene of vibrant traffic. Sailing vessels connected the Indian sub-continent with the Far East on one hand and Persia and Arabia on the other. Linking the Indian peninsula with the Malay world and the Far East was the Bay of Bengal, with several horizontal sea lanes running across to unite ports on either side (Arasaratnam 1986 in Gupta 1994:39). Archaeological evidence suggests that there was trade between India and Thailand as early as 2,000 years ago (Glover 1996:138 in Cooper 2002:13), although indigenous populations of southeast Asia maintained loose contacts with other people much before foreign trade penetrated into this region (Whitmore 1977:140 in Cooper 2002:12). Maritime trade increased considerably in the Bay of Bengal in the course of the second century A.D. (Ray 1989 in Cooper 2002:13). In the first centuries of the Christian era, traders from India and Ceylon sailed across the Bay of Bengal to visit Indonesia for gold and medicinal herbs, an activity later pursued by the Arabs and the Persians (Gupta 1987:240).

1 The spice islands. in a broader sense, cover all those islands lying between the Celebes to the west and New Guinea to the east, with the open Pacific and western Carolines to the north, and Timor and the Arafura seas to the south (Furber 1976:17).

By virtue of their location right in the centre of the Bengal sea, early sailors navigating across could not have missed the Nicobar Islands (Gupta 1994:37, Syamchaudhuri 1977:11). Indian navigators followed two routes while travelling east. While some sailed across the Ten Degree Channel that separates the Andamans from the Nicobars, others passed between Sumatra and the Nicobars. These routes were chosen to avoid notorious pirates of the Strait of Malacca. Chinese travellers sailing from Canton usually halted at Palembang in Sumatra, where they changed ships leaving for Ceylon, the common route being via the Nicobars (Chandra 1977: 190-194, in Cooper 2002:13). Traversing across, it was rather common for sailors to use the Nicobar Islands as a resting place for the replenishment of food and water (Syamchaudhuri 1977:11). As a result, some barter trade took place between the islanders and the sailors. Though the islands were not of any commercial importance to the merchants, to the natives the bartering of food was the only source of certain commodities not available on their islands, such as iron and cloth (Chakravarti 1994:28-29).

Among the Asian seas, the Bay of Bengal has been most intensely traversed in pursuit of maritime commerce for a long time. Owing to the large population on both sides of the Bay of Bengal, there has been considerable trade along its coasts as well as horizontally across to connect any two segments of the two littorals. Given the short travelling time (two to three weeks from any one point to the other within the Bay of Bengal) and the volume of trade that crossed the sea, the returns would have been reasonably satisfactory. The interdependency, it is argued, between the different segments of both coasts had been such that often these segments had more to do with each other than with their hinterlands (Prakash 2002:93). With the discovery and consequent publication of Tome Pires's Suma Oriental in 1944 (written ca. 1514), a great deal has been learned about the maritime trade of Asia as it existed at the time of the arrival of the Portuguese in 1511. Pires, in this classic work, provides a graphic description of the port-to-port trade of Asia. There is now no doubt that besides the Arabs, the Bay of Bengal sea maintained a strong presence of traders from the Coromandel coast (southeast India), Gujarat in western India and Bengal (northeast India). These traders were well connected to the ports of east and far east Asia (the present-day Burma, Malaysia, and Indonesia). Trade lines ran horizontally from west to east, connecting ports on India's Coromandel coast with Pegu, Mergui and Tennaserim on the eastern side of the Bay of Bengal. Most ships crossing the Bay of Bengal horizontally visited the Nicobar Islands during their sojourns for food, or for shelter during storms. These horizontal trading lines were cut by north-south trading routes connecting the ports of Bengal with those of southeast Asia and the Maldives (Arasaratnam 1986 in Gupta 1994:39).

The cargo that was transported across the Bay of Bengal comprised a variety of articles. Indian textiles were in high demand for exchange for spices in the Moluccas and Bandas. Coromandel exported cotton, yam, indigo, tobacco, lac, hides and skins, sandalwood, timber, rattan, drugs, saltpetre, diamond, iron and steel, floor stones, baked bricks, cattle, paddy and slaves. In return, it imported spices, pepper, sandalwood, benzoin, camphor, lac, copper, lead, zinc, gold, silver, tin, drugs, dyestuff, horses, elephants, precious stones, rubies, emeralds and chinaware from southeast and east Asian countries (Gupta 1994:40-41). Apparently, Malacca's prominence as an international port in the fifteenth century had important consequences for the Nicobar Islands. The Nicobar Islands, located conveniently a short distance west of Malacca, provided one of the finest natural harbours in the world that could be used as a resting haven and for the replenishment of food and water for ships en route. The location in the vicinity of Malacca was also one of the reasons why the Danes chose to colonise the Nicobars, as we shall see later.

Among those who carried on the trade over the Bengal sea before 1500 A.D., the Tamils from the Coromandel coast played a predominant role. Next in importance were the Muslim traders from Gujarat. Later, these two groups were to have far-reaching influence on the trade of the Nicobar Islands that exists up to the present day. Already in the fourteenth century, Muslim traders from Gujarat were sailing past the west coast of Sumatra and through the Sunda Strait for trade with the ports of North Java. However, it is still unclear as to when exactly these traders entered the Bay of Bengal trade. Some historians are of the opinion that the Gujarati traders entered the Bengal sea following the void that was created by the withdrawal of Chinese naval expeditions of the Ming period in the second half of the fifteenth century (Gupta 1994:41). Active in the ports of Kedah, Tennaserim, Mergui and Pegu, the Gujarat traders were the biggest group in Malacca (all ports in present day Malaysia) at the time of the arrival of the Portuguese in the early sixteenth century (ibid.).

In this dynamic trade that criss-crossed the Bay of Bengal for centuries, the Nicobar Islands were not passive spectators but were also engaged to a certain degree. Located right in the centre of the sea of influence, they could not have remained insulated from what went on around them. The following sections attempt to describe the role of the Nicobars in the trade and navigation of the Bay of Bengal from early times up to the middle of the eighteenth century. However, a chronological approach to the discussion has to be set aside, since no coherent sources on the subject exist. The attempt here is to reconstruct the picture from the little information that we have. As with the early history of maritime Asia in general, the position of the Nicobars in the trade and navigation of the Bengal sea described here is a reconstruction from chronicles, diaries, travelogues of merchants and occasional travellers.

Early References to the Nicobar Islands

Although the islands must presumably have been known about or visited much earlier, the earliest probable reference to the Nicobars comes from the second century A.D. in the writings of the famous mathematician and astronomer, Claudius Ptolemy. Ptolemy calls these islands Barussae and places them after the Andamans (Kloss 1902:208). However, the first known documents that make a more definite reference to the Nicobars are from the seventh century. Travelling then, the Chinese pilgrim Yuan Chwang writes:

Over the sea some thousands of Ii to the south of the country was Na-lo-ki-lo-chou. The inhabitants of this island were dwarfs three feet high, with human bodies and bird beaks. They did not raise any crops and subsisted on cocoanuts... (Yuan Chwang A.D. 629-644, cited in Chakravarti 1994:20).[2]

2 All the islands south of the Andamans are referred to as the Nicobar Islands. Most of the early travellers while writing about the Nicobars, do not make a distinction between the different islands of the Nicobar archipelago. The same term is used for all of them. It is, therefore, difficult to know which islands were frequented most. In case reference to particular islands has been made in the sources, the same has been mentioned.

Some years later, I-Tsing, another Chinese pilgrim, takes note of these islands, and calls them Lo-jen-kuo or 'Country of the Naked People':

In the twelfth month he [I-Tsing] embarked on a royal ship from there [Ka-chai, i.e. Kedah] and set sail for Eastern India. From Kedah it was a little more than ten days' sail towards north to reach the land of the Naked People. Looking towards the east, the shore - one or two li in extent - contained nothing but yeh-tzu [coconut trees], dense. forests of betel nuts and betel palm. It was pleasant to look at (I-Tsing A.D. 671-695, cited in Chakravarti 1994:21).

In I-Tsing's account the nakedness of the inhabitants was attributed to the curse of Sakyamuni Buddha for stealing his clothes during his visit to the islands (Chakravarti 1994:27). From this time, consequent travellers to the Nicobars used different expressions to refer to the islands as the 'land of the naked people'. Some later Chinese pilgrims and travellers, for example, have called them Luo-Kuo (country of the naked people) and Tch'e-louan-wou (country of uncovered testicles).

The next records are those of the Arabs who frequented these seas in the ninth century. The earliest known Arab document to mention the Nicobars is the Akhabar ai-Sin wa'I-Hind (A.D. 851), formerly attributed to the merchant Sulaiman on his way to South China. In this work, the Nicobars are referred to as Langabalus and Alangabalus, both derived from Sanskrit meaning 'naked man' (Chakravarti 1994:23).

Nagabalus, which are pretty well peopled, both the men and women there go naked, except that the women conceal their private parts with leaves of trees (Pinkerton's collection of Travels, p. 183, cited in Kloss 1902:208).

The first evidence of the Nicobars being somehow "controlled" politically by an outside power comes from an inscription at Tanjore in southern-India, erected aroundA.D. 1030-31. The inscription was raised in connection with King Rajendra Chola's successful campaign to southeast Asia. The dedication refers to the Nicobar Islands as "Nakkavaram in whose extensive gardens honey was collecting". Nakkavaram in Tamil means "naked man" and comes closest to the modern "Nicobar". Besides the fact that the expedition stopped in the Nicobars on the way back to India, it is unclear to what extent such an expedition exerted political control and subjugation on these islands (Chakravarti 1994:31). Historian Tibbetts (1979) cites an Arab document by Rashid aI-din who reports the Nicobar Islands to be a dependency of China in A.D. 1318. It is also mentioned that in A.D. 1346 the Sultan of Bengal presented these islands to the ruler of Barahnakar through the legendary Moroccan traveller Ibn Battuta (Chakravarti 1994:30).

From the thirteenth century, Arab geographers and historians began to call these islands Nakawari, Necuveram and Nakawara, clearly derived from the Tamil Nakkavaram (Chakravarti 1994:23). Constant references to the Nicobars such as these are indicative of the fact that the travellers of those days viewed the inhabitants of the Nicobars as naked or scantily clad. In the same century, Marco Polo, the celebrated Venetian traveller, visited these islands around A.D. 1293. Marco Polo writes:

Concerning the island of Necuveran, when you leave the island of Java, the less (Sumatra) and the kingdom of Lambri, you sail north almost 150 miles and then you come to two islands, one of which (Great Nicobar) is called Necuveran. In this island they have no king nor chief, but live like beasts. And I tell you they all go naked, both men and women, and do not use the slightest covering of any kind. They are idolaters. Their woods are all of noble and valuable kinds of trees; such as Red Sanders, and Indian-nut, and cloves, and Brazil, and sundry other good spices. There is nothing else worth relating (Kloss 1902:209).

The accounts of Ma Huan, the Chinese interpreter who accompanied Cheng Ho, the famous Chinese envoy of the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), on three of his expeditions in the fifteenth century, provides a detailed description of the routes. Sailing towards Ceylon, the expedition crossed the Nicobars and at times halted there for three days. The Nicobars are here referred to as the Ts'uilan-shan or "kingfisher-blue mountain country". The inhabitants of this place were said to be naked and living in caves (Chakravarti 1994:22). Later in 1592, while leading the first English voyage to the spice islands via the Cape of Good Hope, Sir James Lancaster anchored for several days in the Nicobar Islands. One of the officers on board, Henry May, took a note on their appearance:

The people of these ilands goe naked, hauing only the priuities bound up in a peece of linen cloath, which commeth about their middles like a girdle, and so between their twist, a taile hanging downe. .. and upon their heads a paire of homes turning backward (cited in Markham 1877:72).[3]

3 The island that is being referred here is "Sombrero." Kloss (1902: 211 and 106) says it is the Portuguese name for Chowra but since it should be 10-12 leagues north of Little Nicobar it cannot be Chowra: Haensel (1812:25) thinks that "Sombrero" was another name for "Camarty", i.e. Kamorta.

Early Trade in the Nicobar Islands

Already in the early stages of the development of trade in the region, the Nicobar Islands are known to have practiced barter trade. The Nicobar Islands, in former times, offered no real economic advantage to passing sailors who halted primarily for replenishments of supplies. Perhaps this is one of the reasons that there is a paucity of sources to inform us about the ongoing trade in early times. We can even take this as evidence to suggest that the islands themselves did not have a significant role in the early Bay of Bengal trade until the late eighteenth century, when coconuts became even more important as a commercial export from these islands. However, based on a few scattered sources, this section attempts to reconstruct the trading pattern before the year 1750.

It is clear that the Nicobar Islands have been visited by passing vessels for a long period of time. Through this long tradition of contact, the Nicobars came to play their own modest part in the regional trade. Ideally located half-way between the ports of India and east Asia, the Nancowry harbour was constantly used during bad weather by passing ships. Ships that needed repair from damage incurred during their voyages also called upon these islands and used them as a halting place. In the long and arduous sea journeys of early times, which were highly dependent upon winds, the islands provided respite to the sailors who anchored off their coasts to replenish stocks of fresh food and water (Syamchaudhuri 1977:11). In exchange for food (yams, coconuts, chickens, pigs, bananas etc.), the natives received iron, and later cloth as well, from these ships. Besides food, early Arab records suggest that ambergris[4] was the most sought after commodity from the Nicobars, with large quantities of it being transported to Malacca and other places (Renaudot 1733 :4, Barbosa 1921:181, both cited in Cooper 2002:14)[5]. Over time, the occasional barter trade became an integral part of the economic activities of the natives. With the exception of perhaps ambergris, the Nicobar Islands were not commercially important to the merchants as a significant port.

4 Ambergris is an aromatic resin produced in the belly of the great sperm whale. When whales are caught in fast currents and turbulent waters, they vomit a yellowish substance known as ambergris that gathers around the coasts. Used as a fixative in rare perfumes, ambergris has the effect of making other fragrances last much longer than they would otherwise. Apart from this, the Arabs used ambergris as a medicine for the heart and brain, and it was used in the Orient, as an aphrodisiac and as a spice for food and wine. The product continues to fetch a huge price in international markets.

5 Ambergris collected in the Nicobars was used by the Burmese and Chinese for medicinal purposes and was valued highly (Barbe 1847:22), such that the Nicobarese adulterated it with wax and resin to make even higher profits (Dampier 1688 in Kloss 1902:256, Fontana 1799:150, Barbe 1847:21).

To the north of the Nicobars lay the densely clustered Andaman Islands. The Andamans were long avoided by vessels, owing to the belief that the inhabitants of these islands were "cannibals" and would "eat everybody they can catch not of their own race" (Marco Polo 1298, cited in Kloss 1902:177). Only those ships "which have been set back by contrary winds; and compelled to anchor for the sake of water" arrived there but generally "would lose some of their men on these barbarous coasts" (Pinkerton's Collection of Voyages, cited in Kloss 1902:177). With the Andamans strictly avoided, the Nicobars Islands remained a popular stopping-off place for sailors.

In the absence of proper documentation, it is difficult to comment on the exact period during which barter trade in the Nicobar Islands had its origins. There is a likelihood that the islands were visited even before the Christian era, as archaeological evidence suggests that India and Thailand were trading with each other some 2000 years ago (Glover 1996:138, in Cooper 2002:13). But the earliest known account to take note of any aspect of trade among the natives comes from the Chinese pilgrim I-Tsing, travelling in the seventh century:

As soon as the ship advanced towards the shore, the natives seeing the vessel came rushing in hundred small boats. They reached the ship with cocoanuts, bananas, articles made of cane and bamboo and wanted to barter their commodities... In exchange for five or ten cocoanuts they wished to get a piece of iron as long as two fingers (I-Tsing, A.D. 671-695, cited in Chakravarti 1994:28)... If the merchants offered them clothes, they wave their hands (to tell that) they do not use them (I-Tsing, A.D. 673, cited in Gupta 1994:44).

From this, it becomes apparent that the sight of ships and barter trade was nothing new to the natives of these islands. An exchange of goods - however infrequent - did take place between these islands and the outside world even before the seventh century. Apparently, iron was the most sought after commodity and cloth, the most important article in the Bay of Bengal trade, was categorically refused. According to I-Tsing, the native word for iron was lu-ho, derived from the Sanskrit word lauha. This indicates that perhaps the aboriginals received iron from Indian merchants of the Coromandel coast.

The Arab trader Sulaiman, on his way to South China in A.D. 851 was yet another traveller to write his observations during his sojourn on the Nicobars:

When shipping is among these islands, the inhabitants come off in embarkations, and bring with them ambergris and coconuts, which they truck for iron, for they want no clothing, being free from the inconveniences of heat or cold (Pinkerton's collection of Travels, p. 183, cited in Kloss 1902:208).

Later in the same century, a few Arab writers (such as Masudi and AIIdrisi) have mentioned that the natives received clothes from passing merchants. According to Masudi, the natives received clothes in lieu of their produce, and Al-Idrisi adds that the natives wore these clothes purchased from foreign merchants at certain times. Clearly, the acceptance of clothes by the natives - refused at the time of I-Tsing and Sulaiman - was a new development in the trade with the natives of the Nicobar Islands. Al-Idrisi further comments that the natives were open towards foreigners and had no hesitation to enter into commerce with the merchants. That they were open as well as ardent traders is exemplified from the following account of Ibn Babishad written in the Ajaib al-Hind (ca. A.D. 1000):

When a ship is shipwrecked off their coasts, and a man or woman is thrown up on the shore, if the shipwrecked man has saved something than that which he holds in his hand, they will not take for they will not take a thing that anyone who comes among them holds in his hand. They will take the stranger into their houses, seat him down, and give him to eat anything that he wishes and they will not act themselves until he had his fill. They continue to treat him so until the arrival of another ship. Then they will take on board a ship and will receive in exchange a gratuity which the captain of the ship cannot refuse to give if he wishes to save the stranger. Sometimes an ingenious man falls among them who is able to be of use to them in weaving ropes out of cocoanut fibre. They give in exchange for this ambergris. For this ambergris which he keeps until he can find a ship. In this way his stay can be of considerable profit to him (Tibbetts 1979, cited in Chakravarti 1994:29-30).

What is so clearly conveyed in the above narrative is not only the openness of the natives towards outsiders, but also their sharp business acumen that could have only been accumulated through a long tradition of exchange with the outside world.

From the early sixteenth century, with Europeans entering into the spice race, traffic in the Bay of Bengal and the number of vessels visiting the Nicobars increased considerably (Sankaran 1998:2). Besides Asians, the islands were now frequented by several European vessels as well (Kloss 1902:209). The Portuguese often came to these islands to buy food and perhaps even coconuts, which they traded in other places. The fact that the natives had a working knowledge of the Portuguese language[6] is a strong indication of a reasonable amount of contact between the two. By the end of the sixteenth century, the Nicobar Islands had been visited by several prominent European explorers and expedition leaders such as Albuquerque, Durante Barbosa, Jean de Barros, Caesar Frederike, Captain John Davis and Sir James Lancaster (Syamchaudhuri 1977: 13). Cresar Frederike, passing these islands in 1566, writes about the barter trade that went on with vessels that anchored there:

It was the Nicobar custom in 1566 that if any ship come near to that place or coast as they pass that way, as in my voyage it happened, as I came from Malacca through the channel Sombrero, there came two of their barques near our ship, laden with fruit, as with mances (which we call Adam's apples, which fruit is like to our turnips, but is very sweet and good to eat). They would not come into the ship for anything we could do, neither would they take any money for their fruit, but they wquld truck for old shirts or old linen breeches. These rags we let down with a rope into their barque unto them, and look what they thought their things to be worth; so much fruit they would make fast to the rope, and let us hale it in: and it was told me that sometimes a man shall have for an old shirt a good piece of amber (cited in Kloss 1902:209).

6 The use of Portuguese language among the Nicobarese was noted by: Dampier'in 1688 with respect to Great Nicobar (Kloss 1902:258); Hamilton (\799), Distant (\ 874), and Whitehead (1924) noted the same for Car Nicobar; and Hamilton (1739:71) observed the use of Portuguese in the Nancowry islands (Kloss 1902: 102).

Refusing to go on board a European vessel, when otherwise they did, indicates that the natives viewed the first Europeans with suspicion, or even fear. Duarte Barbosa in his Description of the coasts of East Africa and of Malabar (1866) refers briefly to the Nicobars:

In front of Sumatra, across the Gulf of the Ganges, are five or six islands, which have very good water and ports for ships: they are inhabited by Gentiles, poor people, they are called Niconbar; and they find in them very good amber, which they carry thence to Malacca and other ports (cited in Kloss 1902:210).

Stopping by the Nicobar Islands in 1592, Lt. Edmund Barker, the chronicler on board Sir James Lancaster's vessel writes:

And thence to the Hands of Nicubar, where we arriued and found them inhabited with Moores, and after wee came to an anker the people came aboord vs in their canoas, with hennes, cocos, plantans, and other fruits; and in two dayes they brought unto vs roials of plate, giving vs them for calicvut cloth; which roials they finde by diuing for them in the sea, which were lost not long before in two Portugall ships which were bound for China, and were cvast away there (Barker 1877).

And Lancaster himself writes:

Here we had fresh water and some coconuts, other refreshing had we none. Yet the people came aboard our ships in long canoes which would hold twenty men in one of them, and brought gums to sell instead of amber, and therewithal deceived divers of our men: for these people of the east are wholly given to deceit. They brought us hens and coconuts to sell, but held them very dear, so that we bought few of them. We stayed there ten days (cited in Kloss 1902:211).[7]7 Kloss (1902) believes the description to be for either Pulo Milo or Kondul island.

In 1599, John Davis (of Arctic fame) arrived on these islands on a Dutch ship. On arriving in the central Nicobars he writes:

.. . the people brought in great store of hens, oranges, lemons, and other fruit, and some ambergris which we bought for pieces of linen cloth and table napkins. These isles are pleasant and fruitful, lowland, and have good road for ships. The people are most base, only living upon fruits and fish, not manuring the ground, and therefore having no rice (cited in Kloss 1902:211).

The onset of the seventeenth century saw the rise of Dutch supremacy over Asian waters. The Dutch ambitions to monopolise the spice trade had no rival. With militant policies they succeeded in maintaining strong control over the Indonesian archipelago, leaving the English behind in the race. Although, for nearly a century, the Dutch had a strong presence in the Bay of Bengal, no serious effort was made to incorporate the Nicobar archipelago within the Dutch commercial empire, although the presence of some Dutch pirates in the eighteenth century is reported (Gupta 1994:47). There is, however, a story that the Dutch tried to conquer the islands with 800 men owing to a report that on the Nicobars there was a well "whose water converted iron into gold, and was the true philosopher's stone" (Francis Gemelli, ca. 1700, in A Voyage around the World by Dr. John Francis Gemelli Careri, cited in Kloss 1902:178). Whatever the possible reason, we do not know if the Dutch did actually attempt to occupy the Nicobar Islands; there exist no historical evidence or records confirming this (Missionaries' letters 1813).

In 1688, an Englishman by the name of Dampier arrived in Great Nicobar on an English vessel under the command of Captain Read. Dampier's intention had been to desert the ship and stay behind on the island with a "prospect of advancing a profitable trade for ambergris with these people [natives], and of gaining a considerable fortune.." (cited in Kloss 1902:261). After a lengthy altercation with Capt. Read, he succeeded in staying behind but later he barely survived the long illness that followed his long arduous return voyage to Achin by canoe. His original plans of making a fortune by engaging in a local trade of ambergris remained unfulfilled. However, his account of the islands that have survived are by far the fullest from that period. With respect to trade, he writes:

The inhabitants of these islands have no certain converse with any nation, but as ships pass them they will come aboard in their praus and offer their commodities to sale, never inquiring of what nation they are; for all white people are alike to them. Their chiefest commodities are ambergris and fruits. Ambergris is often found by the native Indians of these islands, who know it very well; as also know how to cheat ignorant strangers with a certain mixture like it. Several of our men bought such of them for a small purchase (Dampier 1668, cited in Kloss 1902:256).

Around 1700, another Englishman by the name of Capt. Alexander Hamilton passing through the central group notes:

Ning and Goury [probably referring to Nancowry and Kamorta] are two fine, smooth islands, well inhabited, and plentifully furnished with several sorts of good fish, hogs, and poultry; but they have no horses, cows, sheep, nor goats, nor wild beasts of any sort but monkeys... The people come thronging on board in their canoes, and bring fowl, cocks; fish, fresh, salted, and dried; yams, the best I ever tasted; potatoes, parrots, and monkeys, to barter for old hatchets, sword-blades, and pieces of iron hoops, to make defensive weapons against their common disturbers and implacable enemies the Andamaners; and tobacco they are very greedy for; for a leaf, if pretty large, they will give a cock; for 3 feet of an iron hoop a large hog, and for 1 foot in length, a pig. They all speak a little broken Portuguese... (Hamilton 1739:71, cited in Kloss 1902:102).

Apparently, the Nicobar Islands have since long been visited by the Malays and the Burmese, who visited nearly all islands in their prows[8] to collect ambergris and sea-cucumbers[9] and to purchase from the Nicobarese articles they had collected (Haensel 1812:33, Busch 1845:27, Barbe 1847:1). Swiftlet nests joined the list of exports from the Nicobars after they became an important article in Chinese cuisine and medicine[10] in the sixteenth century (Sankaran 1998:1). However, it is hard to ascertain when exactly the Malays and the Burmese began to visit these islands, but the fact that the Nicobarese spoke a fair amount of Malay (Haensel 1812, Rosen 1839, Busch 1845, Barbe 1847) and, two villages on Car Nicobar have Burmese names (Syamchaudhuri 1977:28)[11] suggests that this link was rather old. Furthermore, the inhabitants of Car Nicobar called the Burmese ta-vai, distinguishing them from other foreigners for whom they have a general name, ta-oiny (Syamchaudhuri 1977:29). A survey in 1931 revealed use of the Burmese language was common on Car Nicobar while the inhabitants of the central and southern islands were familiar with Malay (Bonington 1931:86)[12]. This indicates strongly that the Burmese contacts were with Car Nicobar and that there were Malay contacts with the rest of the archipelago. Though the earliest reference to the presence of Malays and Burmese visiting these islands is from Danish sources of the late eighteenth century, there can be no doubt that their connection to the islands pre-dates these observations.

8 Small boats that are driven with a single sail.

9 Sea cucumbers are gigantic leech-like creatures found among coral rocks. Mainly collected by Malays, they were boiled, then dried and finally packed with lime to be brought to Penang where they were sold to the Chinese as an expensive delicacy (Busch 1845:27, Barbe 1847:22).

10 Swiftlet nests have long been believed to have aphrodisiacal properties and to act as a recuperative after consumptive diseases like tuberculosis. Furthermore, Swiftlet nests are believed to "reinforce body fluids, nourish blood and moisten the respiratory tract and skin; they are believed to replenish the vital energy of life, build up health and aid metabolism, digestion and absorption of nutrients... there are also claims that the birds' nests can prolong life and ageing" (Lau and Melville 1994, in Sankaran 1998:1).

11 Chuk-chu-cha, meaning the 'place where anchor is dropped', and arang, which means 'low land' (Syamchaudhuri 1977:28).

12 Of the 3,632 Car Nicobarese in 1931, 157 could speak Burmese and none spoke Malay. On the other hand, of the 2,531 inhabitants of the central and southern islands together, 793 could converse in Malay and none in Burmese (Bonington 1931 :86).

Besides purchasing what the Nicobarese had collected for sale, the Malays and Burmese additionally engaged in the collection of Swiftlet nests and seacucumbers without giving any compensation to the Nicobarese for the harvest of this resource (Haensel 1812:71). In this sense, to the Malays and the Burmese the islands were not merely a place where they came for trade, but apparently they asserted a certain degree of rights over their resources as well. Hence, the trade with Malays and the Burmese was not really one on which the Nicobarese could depend. It should be noted that ambergris, swiftlet nests and sea cucumbers were collected mainly for the China market (Fontana 1799:150, Haensel 1812:33, Busch 1845:27, Barbe 1847:22). Although the trade in Swiftlet nests on the Nicobars is first reported in some eighteenth-century documents (Haensel 1812:33, Fontana 1799:150), it is likely that they were being collected, if not traded, much earlier. In this sense, the flow of resources from the Nicobars either via trade or extraction or both was quite intimately linked to Chinese consumption for several hundred years. One could even assume that this comprised the bulk of Nicobar exports during this period. Only later, from the nineteenth century onwards, did trade in coconuts became more significant (Temple 1903:243, Man 1903:192, Roepstorff 1881:171).

Early Missionaries in the Nicobar Islands

With the arrival of the Portuguese in Asia at the beginning of the sixteenth century, the Nicobars were no longer confronted with the occasional visit of a ship. Perhaps for the first time there came people who arrived with an intention to actually stay and to impart to the people a new faith with "their strange story of the first woman stealing the orange" (Gardener, cited in Kloss 1902:63). The Portuguese, operating from their base in Malacca on the Malay peninsular, were the first to send Christian missionaries to the Nicobar Islands (Whitehead 1924:25). Unfortunately, there exists no known written record about these first missionaries. The presence of Portuguese missionaries is indicated only from the fact that some Portuguese religious expressions were still in use among the natives at the time of later missionaries. Haensel (1812) notes the use of pater for 'sorcerer' and Barbe (1847) writes on the use of deos and reos for 'God'.[13] According to Whitehead (1924):

In the sixteenth century the Nicobar islands would form part of the Portuguese possessions in charge of the Viceroy of Malacca; but we know nothing further, except that Portuguese missionaries were soon at work in the islands, and that there are a few Portuguese words incorporated in the language (Whitehead 1924:25).

13 Gottfried Haensel, the Moravian missionary, intermittently spent seven years on Nancowry between 1779 and 1788 on Nancowry islands. Rev. Barbe visited these islands briefly in early 1846 on the Danish steamer Ganges.

It is also from Dampier's account that we have the first written evidence of missionaries living on the Nicobars. During his sojourn on Great Nicobar, a vessel commanded by Capt. Weldon touched the island. Capt. Weldon had arrived from Nancowry and had brought with him one of the two friars who were carrying on mission work on Nancowry islands at that time. According to the priest, the natives of Nan cowry:

... were very honest, civil, harmless people; that they were not addicted to quarrelling, theft, or murder; that they did marry, or at least live as man and wife, one man with one woman never changing till death made the separation; that they were punctual and honest in performing their bargains; and that they were inclined to receive Christian religion (Dampier, cited in Kloss 1902:257).

Later in 1711, three French Jesuits from Pondicherry in India arrived to work in the Nicobars (Faure 1711, Missionaries' letters 1813). They were Father Faure, Father Bonnet, and Father Taillandier from the Society of Jesus (Whitehead 1924). Having spent two and a half years in Great Nicobar, they proceeded to other islands and spent ten months on Car Nicobar. It is still unclear whether they died on the islands (perhaps on account of ill-health) or on mainland India after their return (Faure 1711).

Another French missionary from the same order, Father Charles de Montalembart, arrived on the islands in 1726 to explore the possibility of setting up a small trading centre for the French East India Company and to establish a Christian mission. He returned to Pondicherry after a stay of one year on the islands, dying soon after from a fatal disease he had acquired in the Nicobars (Mathur 1968:272).

The System of Inter-Island Trade in the Nicobar Islands

An important phenomenon that cannot be overlooked when discussing the trade history of the Nicobar Islands is the system of inter-island trade that was in practice at least until two decades ago (Sahay 1976, 1979). It may be termed "system" because there existed for centuries a regular interaction concerning exchange of certain goods between the different islands. Different islands specialised in different products that they bartered with other islands via longestablished friendly connections and in some cases, even kinship ties. The system was regulated by a set of traditional rules and conventions, and in some cases, accompanied by elaborate magical rituals and public ceremonies. The period for this inter-island trade was between December and April, a relatively dry season marked by the northeast winds. The origins of this system of interisland trade are not known, but it can be assumed that it has existed for several centuries, perhaps even millennia.

The first mentions of inter-island trade, however, come only from two Europeans, Hamilton (1799) and Fontana (1799), who visited these islands during the last quarter of the eighteenth century. Their observations, however, are somewhat limited to the barter trade between some islands and do not articulate the situation of the archipelago as a whole. More evidence of this is obtained from nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century accounts that are more complete than those of the preceding century (e.g. Rosen 1839:206, Barbe 1847:11-12, Temple 1901:217, Whitehead 1924:18-19, Man. n.d.[14]).

14 E. H. Man was a senior British officer who served in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands from 1869 to 1901. He published a great many works relating to the aboriginals of Andaman and the Nicobar Islands. The work cited here is a book that was compiled posthumously from papers he published in the Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute and in the Indian Antiquary, and from notes prepared for publication before his death in 1929. Somehow this book does not mention the date of its publication, but some authors have assumed it to date from 1933.

Only as late as 1962, by the German scholar Klaus Mylius, was a more coherent attempt made in this direction. However, Mylius' paper is based only on earlier published sources, since he himself never visited the Nicobar Islands for fieldwork. The first lucid, field-based account comes from the Indian anthropologist, Vijoy S. Sahay (1976, 1979), apparently the last witness to the system of inter-island trade as it existed then. Given that the earliest accounts are from the late eighteenth century, it is impossible to ascertain the form in which the system of inter-island trade existed - if it did exist - before the arrival of the Europeans. At best, we can only attempt a vague reconstruction of the situation that might have existed around 1750.

The earliest known mention of inter-island trade comes from Hamilton (1799) who notes the practice of annual trade that takes place between the islands of Car Nicobar and Chowra:

They [Car Nicobar] purchase a much larger quantity of cloth [from passing ships] than is consumed upon their own island. This is intended for the Choury market. Choury is a small island to the southward of theirs, to which a large fleet of their boats sails every year, about the month of November, to exchange cloth for canoes; for they cannot make these themselves (Hamilton 1799:340; emphasis in original).

Fontana (1799) tells us that there was a similar practice between Nancowry and Great Nicobar during the same season:

At the fair season, or the beginning of the NE monsoon, they sail in large canoes to the Car Nicobars [actually Great Nicobar] called by them Champaloon [also written as Shambelong]. The object of this voyage is trade; and for cloth, silver coin, iron, tobacco, and some other articles, which they obtain from Europeans, together with fowls, hogs, cocoa and areca nuts, the produce of their own island, they receive in exchange, canoes, spears, ambergris, birds' nests, tortoise shell, and so forth (Fontana 1799:155).[15]

15 Fontana's account is rather inaccurate in terms of island names and their geographical location. However, the description of trade articles, when compared with later accounts. corroborates with that of the trade between Nancowry islands and the southern group.

Traded articles such as cloth, silver, coins, tobacco and iron were definitely not the produce of the Nicobar Islands, but had been traded with passing vessels. It thus becomes obvious that already in the eighteenth century, a system of exchange had been established that inextricably linked inter-island trade with foreign trade. As mentioned in the previous chapter, the islands most frequented by foreign vessels in the archipelago were Car Nicobar (the northernmost island), followed by the sheltered waters of Nancowry, Kamorta and Trinket islands (the central group). Lying on an ancient sea route, Car Nicobar had traditionally attracted a larger number of foreign vessels wishing to renew stocks of food and water, and later for the trade in coconuts (Syamchaudhuri 1977:13). Car Nicobar produced the most coconuts in the entire archipelago followed, respectively, by Kamorta, Trinket, Bompoka, Teressa and Katchal (Man n.d., 110). The popularity of Nancowry islands on the other hand owed much to its excellent natural harbour. Although not comparable with Car Nicobar in terms of coconuts production, ships often took advantage of the safe harbour in bad weather while replenishing themselves with food and water via the barter trade with the natives (Syamchaudhuri 1977: 13).

Given such geographical and natural factors, both Car Nicobar and Nancowry islands had most access to foreign goods, some of which (such as linen, iron and tobacco) were extremely coveted throughout the archipelago. With the growing frequency of contacts with passing vessels, especially after the arrival of the Europeans, it can be expected that the amount of barter trade also increased. From the accounts of Hamilton and Fontana and also from later reports, it appears that these "foreign goods" came to be included in the "products" of Car Nicobar and Nancowry that could be further traded with other islands.

The Danes, were the first to maintain an establishment in the Nicobars, intermittently between 1756 and 1848. The first document to provide some information on inter-island trade relations was the book of Pastor David Rosen, published in 1839.[16] While a detailed account of Rosen's stay and activities is discussed in the next chapter, it is sufficient to mention here that he officiated as the "Resident" of the Danish settlement on Nancowry islands from 1831 to 1834 (Rosen 1839). In his book, published five years later, Rosen provides the first complete overview, however brief, of the ongoing trade between the different islands of the archipelago:

Between the South Nicobar islands and the islands by the harbour [i.e. Nancowry harbour], there is active communication which starts in November. The northern islands purchase bamboo cane, swallow nests [Swiftlet nests] and turtle shells and so on which exist in greater quantities in the southern islands. In return, they bring canvas, tobacco and large clay pots. Between Katsjul [Katchal], Teressa, Bompok and the islands at the harbour there exists a continuous communication. The most important article from those islands is the big clay pots. Teressa and Bompok trade with Chowra, which is the best cultivated of all the islands. At Chowra, they get hold of their big clay pots which are desired by all the Nicobars. The inhabitants of Chowra are the only ones who have permission to trade with Car Nicobar. They provide the inhabitants of Car Nicobar with products from the southern islands through regular contacts. They are jealous of everyone who tries to break this pattern of trade. (Rosen 1839:206, cited in Wallin-Weihe 1999:136).

16 Gottfried Haensel, while providing a detailed account of the sufferings of the Moravian missionaries in their bid to survive and preach the gospel, gives little information about native culture and nothing is mentioned in terms of trade.

It is from Rosen's account that we first learn of the central role of Chowra in the dynamics of inter-island trade, and this corresponds closely to what later accounts and studies have established (e.g. Barbe 1847:12, Temple 1901:217, Kloss 1902:308, Man n.d., 33-34, Whitehead 1924:20, Mylius 1962, Sahay 1976, Syamchaudhuri 1977:30-33, Sahay 1979). The pivotal role of Chowra in island trade rests on its privileged position in having a monopoly upon the manufacture of clay pottery. The origins of pottery-making on Chowra are not known but "a belief exists that in remote ages the Great Unknown, whom in later times they were taught by the missionaries to call Deuse, decreed that on pain of certain serious consequences - such as an earthquake or sudden death - the manufacture of pots was to be confined to the one small island of the group known to us as 'Chowra', and that the entire work of preparing the clay and moulding and firing the pots was to devolve on the women of the community" (Man 1894:21). Traditionally, Chowra has had the reputation of being the "home of magic in its most powerful form" (Whitehead 1924:137). And the production of clay pottery was believed to be inextricably linked to black magic that Chowra alone had mastered. Hence, throughout the archipelago it came to be tabooed, and even feared, so that no one except an inhabitant of Chowra is permitted to make cooking pots (Man 1894:21, Kloss 1902:107, Whitehead 1924:20). Furthermore, pork cooked in any vessel other than a Chowra pot would inevitably bring misfortune on the one who consumes it (Man n.d., 33). More than two centuries ago, Fontana (1799) noted the grave consequences suffered by the people ofNancowry for violating this taboo:

Some of the natives, having begun to fabricate earthen pots, soon after died; and the cause being attributed to this employment, it has never been resumed; since they prefer going fifteen or twenty leagues to provide them, rather than expose themselves to an undertaking attended, in their opinion, with such dangerous consequences (Fontana 1799:154).

Again, 100 years later, E.H. Man, a British officer posted in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands penal settlement writes in this respect:

.. .many years ago a Chowra woman while on a visit in one of the central islands thoughtlessly acted in contravention of the prohibition and attempted to make a cooking pot, but she forthwith paid the penalty of her disobedience with her life. This incident has consequently been held as confirmatory of the genuineness of the command and a warning against any rash trifling with the restrictions, which though imposed in far-off times, are yet of importance to be observed (Man 1894:22).

The threat of death and disease were not the only reasons that prevented other islands from manufacturing pots, but the use of Chowra pots had advantages, too. Meals cooked on Chowra pots were believed to bring fortune and prosperity, and water boiled in such pots was believed to immunise children who bathed in it against the negative effects of black magic (Sahay 1976:88, Sahay 1979:288).[17]

17. For a description of the pottery production process, see Kloss (1902:107), Man (1894:24-27), and Sahay (1976:90-91).

In addition to pottery, the people of Chowra also specialised in racing canoes, containing magic, which they supplied to Car Nicobar, Teressa and Bompoka islands (Sahay 1976:92). To the Nicobarese, canoes are the main means of transportation, whether travelling to different islands or to other villages on the same island that are invariably located along the coast (ibid., 91). Nicobarese canoes are of three types, depending on the island of manufacture: Chowra, Nancowry, and Kondul types, the last two being rather similar, except Nancowry canoes are a little smaller than those from Kondul (ibid.). Both .Kondul and Nancowry exported some of their canoes to Chowra and these were further passed on to Car Nicobar, Teressa and Bompoka (ibid., 92). However, Chowra made considerable profit in acting as middle-men between the central islands and Car Nicobar to the extent that there was sometimes resentment among the Car Nicobarese (Whitehead 1924:19). It was once calculated that a canoe sold by Nancowry to Chowra for Rs. 25 was further sold to Car Nicobar at 105 (E.H. Man, cited in Kloss 1902:308).[18] As in the case of pots, canoes from Chowra also had magical connotations. A canoe purchased from Chowra would receive appropriate treatment as an animate object with supernatural powers and was continuously fed and respected (Syamchaudhuri 1977:32).

18 The amount mentioned here was derived by converting the articles that were actually used in the barter into rupees (Kloss 902:308).

Trade relations between Chowra and Car Nicobar in particular were characterised by ceremonial voyages to each other (Whitehead 1924:19, Sahay 1979:288). During each dry season, guided by the northeast winds, a group of natives from Car Nicobar undertook a trip to visit their "old friend" at Chowra. The primary objective of this "pilgrimage" was to obtain the "sacred" clay pots and canoes in lieu of pigs and goods they had purchased through foreign trade. The annual voyage to Chowra also yielded the opportunity to the youths of Car Nicobar to be initiated into the mysteries of life by the great "masters" Iselves (Whitehead 1924: 19). According to Whitehead (1924: 138), these annual voyages undertaken by the Car Nicobarese to Chowra took place using only canoes which had been made by or purchased from the people of Chowra. It was regarded as sinful by the people of Chowra for any other canoes to land on their island (ibid.). Conversely, natives of Chowra paid an annual visit to their "regular customers" in Car Nicobar for the exchange of similar goods, receiving orders of canoes, fixing the barter price, and to settle old dues (Syamchaudhuri 1977:32, Sahay 1976:95). This trading relationship between fixed partners continued over generations. Friendly visits were exchanged regularly with an implicit objective to trade. In both cases, the event was marked by sacred rites and strict adherence to certain customs (Whitehead 1924:136-146, Sahay 1976, Sahay 1979).

|

Long, long ago the ancients who lived here [Car Nicobar] did not know that there was another country in the world besides this island; for it is situated in the middle of the ocean. Now it happened that some people once made a toy canoe from the spathe of the coconut. They finished it off very carefully, and fixed sails for it. And after they had done this they put into it a cargo of small yams, and then they floated off the canoe in the direction of Chowra. The canoe was some months on its journey; but at last it reached Chowra. Someone found it and carried it off. As soon as the foreigners who live at Chowra saw it, they said: "Perhaps there is some small country over yonder, and this small canoe has been made by those people and laden with yams. Come, let us (in our turn) lade it with a tiny pot and some kui-löi. So the tiny canoe was sent off again, this time in the direction of our country; and it duly arrived with its cargo of a small cooking pot and some kui-löi; and the people of these parts found it and carried off the cargo. "What can we make of this? Perhaps it would do to boil water in, to cook our food", said they, as they examined the cooking pot. So they put some water into it, and it did not leak. They then put it on the fire and heated the water; the pot did not crack or leak. Then they put some food into it and cooked it. Then they remarked one to another: "Perhaps there will be some big ones too, where this little cooking pot came from; so let us go in our canoes and find out; for we are badly in want of something to cook our food in". So, after some months, the people here again sent off the toy canoe, and took their own canoes and followed it; and in due course came to Chowra. But they were just missing the way and going on to Luröö, when the people of Chowra saw them, and beckoned them to come ashore there. So they went ashore there, and purchased big cooking pots as their cargo for the return journey. From that time onwards the peoples of Car Nicobar and Chowra have been great friends (or especially associated together); and we regularly take goods there wherewith to buy our cooking pots. Source: Whitehead 1924: 261-262 |

Figure 5.1. Inhabitants of Chowra and their pottery (ca. 1900).

Courtesy Museum für Völkerkunde,

Vienna

It is interesting to note that none of the raw materials required to produce pots or canoes were available on Chowra. Originally, however, the pots were manufactured from the clay that was once available on Chowra itself. Over time, the clay was exhausted and had to be fetched from Teressa, an island some five miles to the south (Man 1894:22, Whitehead 1924:19, Sahay 1976:92).[19]. Fetching clay from Teressa involved some ceremony and was subject to certain regulations. Vijoy S. Sahay, who accompanied the group from Chowra to one of their (perhaps last) voyages to Teressa, reports on the process:

During a calm season Chowrians unanimously decide to fetch clay from Teressa. A meeting is held in the presence of the Chief of the island, all the fourteen witch doctors and the heads of all the families. A date is fixed for the expedition. On their voyage they carry everything in odd numbers, i.e. the number of persons, of canoes, of coconuts, of fishing hooks and of lines, etc. They wear only black or red loin cloth during the voyage... When people reach Teressa they go to a particular place and as soon as their canoes enter the calm and still waters of the shore, everybody stops singing as well as talking. This place is held sacred. It is so believed that violation of the rule would cause death and disease in Chowra and that vegetables would cease to grow there. A perfect silence is therefore maintained. No body speaks in his local dialect. When necessity arises, they communicate either by signals or by driving their canoe away from the shore. They land ashore and start collecting clay by their hands. Several heaps of clay are made and a small plant, which is easily available in the vicinity is plucked and placed on the top of each clay-lump. Then the clay is brought aboard the canoe. On completion of the job they leave the place in silence. This is all done in perfect harmony. As soon as they leave the place, they again start singing as before and joyfully return home (Sahay 1976:90).

19 Sahay (1976, 1979) describes vividly how the process of fetching clay from Teressa was interspersed with several rites and adherences.

Ironically, Teressa had to purchase pots made from their own clay from Chowra (Man n.d., 33). Furthermore, since neither Chowra nor Car Nicobar had suitable trees for making canoes, the Chowrites were obliged to go to Teressa or Nancowry islands to negotiate a suitable tree in exchange for their pots and labour (Sahay 1976:92). Since the custom of cooking food on Chowra pots, particularly during festive occasions, was followed throughout the archipelago, the demand for these pots was not limited to Car Nicobar alone. They were used as far down south as Great Nicobar [20]. However, there existed yet another taboo: the people of Chowra were strongly opposed to a direct trade with the southern group of islands, that is, with Kondul, Pilo Milo, Little Nicobar and Great Nicobar. It was believed that even a speck of sand from the southern islands could destroy Chowra (Sahay 1976:92). This complicated situation was solved by the central islands (i.e. Nancowry) playing a middle role between Chowra and the southern islands. Yet another prohibition involved the manufacture of lime. It was maintained that lime produced by burning sea-shells could only be made in the southern group, Katchal and some villages within the Nancowry harbour, and that produced by burning corals, on Car Nicobar alone (Kloss 1902:107, Barbe 1847:12).

20 Dampier, in 1688, noted the use of Chowra pots on Great Nicobar in which they boiled pandanus (Kloss 1902:259).

The monopoly upon manufacturing pots was perhaps the most significant taboo with severe consequences. Owing to this fact, we find that Chowra had a central place in the entire trade of the archipelago. The Chowrites specialised in the manufacture of pots and canoes which they directly exported to Car Nicobar and to the central islands. In return, Car Nicobar provided them with foreign goods and pigs. The central islands in exchange supplied them with foreign goods, lime, timber for making canoes, as well as goods which they import from the southern group, namely honey, rattan and canoes. The central islands supply the southem islands with Chowra pots and foreign goods (Sahay 1976, Sahay 1979, Mylius 1962).

With a high population density[21] and scarce natural resources, Chowra's dependency on inter-island trade is understandable. With just enough coconuts for their own needs, the island was not very popular with foreign vessels either (Whitehead 1924:20). Hence, the island's requirements for non-island goods (such as cloth, iron, and tobacco) and other natural products (such as pigs and rattan) had to be met from other islands. But clearly, they had to offer something in return. The inhabitants' remarkable skills in the manufacture of pottery and canoes coupled with magic perhaps developed as a way out of this resource constraint. Furthermore, owing to its central location beween Car Nicobar and the southern islands, the island of Chowra served as a place of anchorage for canoes sailing from Car Nicobar on their way to the southern islands. Those violating the trade regulations were immediately refused anchorage (Syamchaudhuri 1977:32). R.C. Temple has summed up the trade ofChowra as follows:

Chowra is the holy land, the cradle of the race, where the men are wizards, a belief that the inhabitants of Chowra turn to good account for keeping the control of the internal trade in their own hands (Temple 1909:41).

21 In the 1960s, Chowra had a population density of 600 inhabitants per square mile (Sahay 1979:290).

While Car Nicobar was known to lead in matters of foreign trade, Chowra was the centre of the inter-island trade (Man n.d., 33); both were indispensable in their own way. However, the association of magic with Chowra pots and canoes elevated Chowra, much to Car Nicobar's resentment, to a far superior position in the entire archipelago. In any case, trade relations between Chowra and Car Nicobar were perhaps the most long-established and the frequent, when compared to that with other islands further south. Due to this recurrent contact, it is probable that the southernmost village of Car Nicobar, Kimios, was originally populated by immigrants from Chowra who moved out due to population pressure. One fact supporting this is the similarity in the dialect spoken by inhabitants of Kimios and those of Chowra (Syamchaudhuri 1977:33).

The system of inter-island trade appears in some ways similar to the caste system on mainland India among the Hindus, whereby a particular caste was obliged to produce the same goods through generations. But while in the caste system there was a strict hierarchy, this doesn't appear to be the case in the Nicobars. Chaurites, despite being the most powerful with their black magic, were nonetheless compelled to sell their labour to the people of Teressa and Nancowry by working in their plantations or helping them thatch their roofs if they wished to receive products from their islands (Sahay 1976:92). The system of inter-island trade in the Nicobars, as we see, was kept in balance and regulated with accepted norms, restrictions and taboos. Every island depended on the others for different products. But it was perhaps a system that went beyond trade, that is, to maintain an uninterrupted intercourse between the people of different islands.

|

In 1896, a canoe from Chowra was sold to some people at Car Nicobar. The canoe was first valued at 35,000 coconuts, but the payment was not made in actual nuts, instead in articles that the Car Nicobarese had obtained from foreign trade. Below are the articles, valued in coconuts, delivered in exchange for the canoe:

|

While discussing the inter-island trade of the Nicobars, it might be interesting to compare this with Malinowski's famous Kula Ring in the Western Pacific. The Kula is described as "a form of exchange, of extensive, inter-tribal character; it is carried on by communities inhabiting a wide ring of islands, which form a closed circuit" (Malinowski 1922). The exchange takes place primarily in two kinds of articles: long necklaces and red shell that invariably travel clockwise in the archipelago, and bracelets and white shell that are passed on in an anti-clockwise direction. These articles are changed constantly in their respective directions but remaining within the defined circuitous path. Though not of much "practical use" themselves, the significance lies in the prestige these articles carry with them. However, alongside the ritual exchanges of arm-shells and necklaces, ordinary barter trade in utilities between islands also takes place, the latter being only of minor importance (ibid.). The inter-island trade of the Nicobars is similar to the Kula insofar as the trade continues between established partners for long periods of time. However, while the essential aspect of the Kula is the exchange of arm-shells and necklaces, articles of practically no use, the contrary is true for the Nicobars. One may, however, argue that the Chowra pot without its supernatural attributes - as harbinger of good fortune and immunization against black magic - does not offer much practical utility as well. Had it not been for these magical attributes, Chowra pots would have with much ease been substituted by other containers obtainable from foreign trade[22]. Articles in the Kula, however, are rarely worn and are retained only temporarily by the owners before they are once again passed on. This is not the case with Chowra pots, which are definitely used and permanently owned by those who purchased them until they are of no further use. Therefore, the fact that articles are "once in the Kula, always in the Kula" (Malinowski 1922) does not hold true for Chowra pots, let alone for other articles. In both cases, however, the trading partners are bound by mutual duties and commitment to assist, should an occasion arise.

22 In effect, early in the twentieth century, the British threatened to destroy the Chowra monopoly, and thereby the inter-island trading system, by introducing identical Chowra pots manufactured at Port Blair if the inhabitants of Chowra did not submit to British authority (Man 1903:161). The British were aware of the increasing antiChowra feeling on Car Nicobar leading some to already defy Chowra authority based on magic. More of this is discussed in a following sction, The British Period.

From the earliest available accounts up to the middle of the eighteenth century, we find several changes in the trading pattern of the Nicobars. The major demand in early times, as it appears, was only for the iron that probably first came to them from Indian traders visiting the Malay-Indonesian region in the early centuries of the Christian era. Clothes, which the natives had categorically refused, began to be accepted from the ninth century onwards. The initial demand was for old worn clothes and later, perhaps with the arrival of the Europeans, for fabric and linen. Tobacco, demand for which only spread in later centuries, first came to be bartered sometimes during the course of the seventeenth century, or at least the first mentions of the demand for tobacco are from this period (Hamilton 1739:71, cited in Kloss 1902:102).

It is difficult to determine the extent of impact the early Europeans exerted on the trade of the Nicobar Islands. With the arrival of the Europeans, it can at least be assumed that the frequency with which ships visited the Nicobars increased considerably, causing a significant augmentation of the barter trade. The goods in demand were mostly pieces of iron, old hatchets, sword blades, coarse linen, clothes and tobacco. It can also be expected that the frequency and the regularity of vessels arriving and an increased amount of barter trade gradually saw the beginnings of the incorporation of these traded articles into their material and social fabric. Yet there is little documentation of the extent to which this occurred. The constant exchanges involving iron, old clothes and linen among the natives are evidence in themselves of a development in the direction of material change. Iron was by this time well incorporated in making tools and weapons (Hamilton 1739:71, cited in Kloss 1902:102) and both men and women wrapped pieces of cloth around their loins[23].

23 Dampier, visiting Great Nicobar in 1688 notes: "The men go all naked; only a long, narrow piece of cloth or sash, which, going round their waists, and thence down between their thighs, is brought up behind and tucked-in at that part which goes about the waist. The women have a kind of a short petticoat, reaching from their waists to their knees" (Dampier, cited in Kloss, 1902:258).

[ Go to HOME

] [ Go to HEAD

OF NICOBAR CHAPTER

]

Last changed 12 March 2006