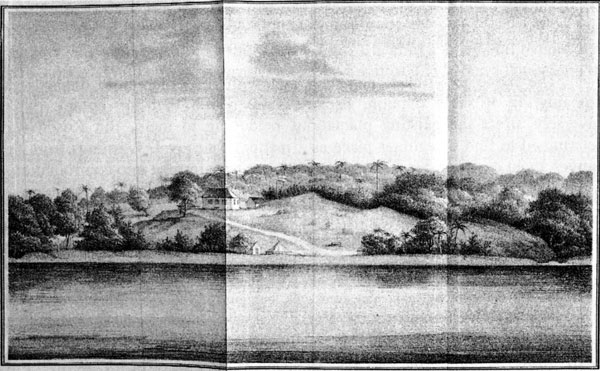

Figure 6.1. Ground map of the Danish Colony, Kamorta Island (Source: From the book of David Rosen, 1839)

The Nicobar Islands

The Danes in the Nicobars

by Dr. Simron Jit Singh

|

The following text was originally published as Chapter 6 (pp. 155-196) of S.J. Singh's In the Sea of Influence - a world system perspective of the Nicobar Islands, Lund Studies in Human Ecology 6, Lund University, Sweden, 2003, ISBN 91-628-5854-8, ISSN 1403-5022. A sub-section of Chapter 6, "Proposals for Colonising" is not reproduced here. Copyright ©2003 Simron Jit Singh Footnotes are marked in the text with square brackets [ ] and can be found at the end of the following paragraph. For references mentioned in the text consult the printed book. |

The term "Danish period" broadly refers to the era when the Danes theoretically were the European "owners" of the Nicobar Islands. However, during this period, the islands were occupied briefly by the Austro-Hungarians (henceforth referred to only as Austrians) from 1778 to 1783, and later by the British from 1807 to 1814, the time when Denmark and Britain were at war with each other. Though neither the Austrians nor the British undertook any substantial activities on the Nicobars during their period of occupation, their story has been included in this chapter for the sake of continuity.

The chapter is split into four sections: the first narrates the story of the several Danish attempts at colonising the islands, and describes some of their major activities; the second outlines two non-implemented proposals for colonising the Nicobar Islands; the third focuses on the trading world of Nicobars during this period; and the fourth contains some general conclusions on the period as a whole. It must be noted, however, that although the Danes "owned" these islands politically, at no time did they dominate its trade. Other nations, European or Asian, still carried on their trading activities with the natives without any interference from the Danes. Moreover, as we shall see, the Danish period is interspersed with several attempts to establish a colony. At no time did the Danes have a properly-running administration that regulated the day-to-day affairs of the natives nor did they ever have control over vessels that passed or traded in the Nicobars. In fact, the story of the Danish period is in some ways distressing, on account of the Danes' perpetual struggle for survival.

Hence, this discussion of the trade of this period is not limited to the role of Denmark alone, which in this respect was only marginal, but includes others trading in these islands and for which some information is available. I have repeatedly stated that the Nicobar Islands as they were had little economic significance for merchants, in comparison to the famous ports of Malacca and Java. Their attraction primarily lay in their potential conversion into a famous port like Singapore or Batavia. Whoever might succeed in this endeavour stood to make a fortune. Although the Danes tried incessantly to transform the Nicobars, they met without success. Unfortunately, for this period, there is a lack of consistent information and sources that inform us about the trading patterns and the volume of goods being traded in the Nicobars. Once again, this chapter draws on most of what is available in order to reconstruct the trading pattern of the period and to follow its development and impact. However, before I turn to the Danish presence in the Nicobars, I would like to briefly summarise the reasons for Danish presence in India.

Already in the seventeenth century, the axis of interest in Europe was strongly focused upon the East, and specifically upon an India-oriented setting. The success of the English and the Dutch in the spice trade, who together imported over five million pounds of pepper alone to Europe annually (Gupta 1987:267), made it increasingly difficult for the Danes to accept being passive spectators watching their neighbours become wealthy overnight. At the instance of two Dutch merchants, King Christian IV, monarch of the dual kingdom of Denmark-Norway (here referred to as Denmark), was quick to issue a charter - almost identical to that of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) - in 1616, giving the newly-founded Danish East India Company a monopoly on trade between Denmark and Asia for twelve years (Subrahmanyam 1989:43).

According to the advice of Roelant Crappe, a Dutchman originally in the service of the VOC in Asia, the first expedition set sail in 1618 with the intention of establishing a Danish settlement near Tanjavur on the Coromandel coast. The reasons for choosing such a site were two-fold: firstly, neither the French, the English nor the Portuguese had strong presences in that area, and secondly, it was a place through which most of the pepper arrived overland from Malabar, fetching the nayak (the local potentate) a revenue of five hundred rials a day (Subrahmanyam 1989:44). In 1620, a treaty was concluded between the nayak and the King of Denmark by which the Danes were given the permission to erect a fortress at the village of Tranquebar (or Tarangambadi) on the Coromandel coast (Subrahmanyam 1989:45).

In the first years, Danish ships busied themselves with "country trade'[1] and freighted peppers and cloves from Tenasserim (or Mergui) and Macassar to Tranquebar. After 1625, the Danes ceased trading for themselves on these routes and instead became carriers for Portuguese goods functioning as neutral third parties in the comprehensive trading networks of the Bay of Bengal. In 1625, lesser trading centres were also set up in Masulipatnam, Pipli and Balasore (Subrahmanyam 1989:47). Already in 1627, however, the financial situation of the Danish East India Company was such that they were unable to pay the agreed tribute to the nayak. The situation worsened following a succession of illjudged investments by Barent Pessart, a Dutchman who succeeded Crappe as leader of the colony (Rasmussen 1996:3-4). Between 1622 and 1637, only seven ships, chiefly with cargoes of pepper and cloves, returned to Denmark out of the eighteen that had left home. As a result of the unreliability and irregularity of its trade with Asia, Copenhagen failed to become one of Europe's trading centres in Asian goods (Feldbaek 1991:3).

1 Nearly all Europeans active in the East Indies before 1800 were living two lives - one as servants of European governments or East India Companies, another as individuals participating for their own advantage directly or indirectly in the port-to-port trade within the eastern seas known as "country trade" (Furber 1976:4), More recently, some have given preference to the term "Intra-Asian trade", However, Furber (l976:341) is of the opinion that "Intra-Asian" is not broad enough in meaning, for a voyage between any port on the east coast of Africa and any other port in East Africa or Asia is just as much a "country" voyage as one between two or more ports in Asia.

The war with Sweden and the death of King Christian IV in 1648 left the ailing company largely to its own fate, although it somehow continued with disputes over leadership, private trade, shipwrecks and losses. In 1650, King Frederik III, following an appeal by the council of the realm, abolished the Danish East India Company. Tranquebar, however, still remained a Danish colony under the King. There were subsequently some attempts to sell the colony to the Elector of Brandenburg, but payment was not released as agreed and so the deal fell through (Rasmussen 1996:4). For 29 years, however, no ship arrived at Tranquebar from Denmark. When a ship was sent, in 1669, this was only in response to persistent reports sent by the only surviving Dane, Eskild Andersen Kongsbakke, who had held the colony against all odds (Larsen 1907:39-40). The ship's return to Denmark in 1670 with a cargo of pepper and spices raised optimism among the merchants of Copenhagen, and the same year, the young monarch Christian V appended his signature to the charter of the second Danish East India Company (Feldbraek 1991:4).

The second Danish East India Company fared slightly better than the first, even though they, along with the English, were forced out of the East Indies by the exclusion policy of the Dutch. The late-seventeenth century wars among the great maritime powers, due to the Anglo-Dutch rivalry over eastern trade provided an opportunity for the Danish East India Company. Denmark's neutrality during the wars earned them large profits since trade still continued, albeit only with neutral ships and neutral ports. Cargo comprised mainly of pepper, though also a small proportion of sugar, Indian textiles and saltpetre (used in the production of ammunition), was also included. The outbreak of the Great Northern War in 1709 marked the decline of the second company and even though peace was achieved in 1720, the company's finances and competitiveness had been immensely weakened. The refusal of Frederik IV to save the company with a loan forced the company directors in 1729 to hand over the charter and Tranquebar back to the crown, having made a total profit, during its existence, of nearly three million rix-dollars or about 600,000 pounds (Feldbrek 1991:4). The Danes, however, were not to be intimidated either by their former losses or by the monolithic trade monopolies of the Dutch, English and French. In 1732, King Christian VI appended his signature to a somewhat different charter, founding what came to be called the Danish Asiatic Company (ibid., 5).

Managing to avoid involvement in war and conflicts, and building upon the former trading connections of its predecessors, the Danish Asiatic Company made remarkable progress. Regular trade with India and China was established. The Anglo-French war that reached the East in 1744 (as a consequence of the.

Austrian War of Succession) profited the company once again. As neutral thirdparty carriers during wartime, the Danes benefited greatly and the amount of cargo to be transported increased substantially. Consequently, a period of economic boom was ushered in for the Danes that continued well after the war ended in 1763 (Feldbrek 1991 :7). Between 1743 and 1750, the company's annual balance sheet doubled. In 1751, both the company and the Danish government embarked on a programme of expansion, of which the occupation of the Nicobar Islands was to form a part (Furber 1976:214).

In November 1754, a clandestine assembly of high-ranking Danish officials had gathered at their Indian headquarters at Tranquebar. Present among them were the Director of the Danish Asiatic Company and Governor Krog, who represented the Royal Danish colony of Tranquebar in India. The meeting was the outcome of a recent report submitted to the Danish Government at Tranquebar by Priest Husfeld, a Moravian missionary recently returned from the Nicobar Islands. The report described the Nicobars as an excellent place for planting pepper, cinnamon, sugarcane, coffee and cotton. Further, besides their local resources of coconuts and arecanuts, the islands were said to be located suitably to become a centre for Indian trade and ship-building industry due to their abundant timber resources (Möller 1797:483-484).

The tropical islands, often the first landfalls and navigational points of reference, were to become the first colonies (Grove 1995:32). Preferred islands were those that lay strategically (in both supply and military terms) on the trade routes to India. The colonisation of St. Helena and Mauritius was thus obvious and gained prominence in most of the travel literature of the period (Grove 1995:42). By the mid-seventeenth century, tropical islands were looked upon as a warehouse of rich resources, and as offering immense economic opportuniti in particular for their high plantation potential. Again, St. Helena and Maurit were the first to undergo resource exploitation and a phase of (successf systematic forestry and monoculture plantations (Grove 1995:9-10). By 1 eighteenth century, there further developed an urgent need to understa unfamiliar floras, faunas and geologies for commercial exploitation and medii purposes. Consequently, the environments of tropical islands came to be ev more highly prized (Grove 1995:8).

Husfeld's plan to colonise the Nicobars was a timely one and greatly appealed to the secret assembly. The Company's directors in no time issued orders to start investigations - in secrecy - for an establishment to be created the Nicobars. The following year, in August 1755, another clandestine meetingwas called to address the final plan for the Nicobars. The time was ripe, France and England were still at war. However, it was feared that France would attempt to occupy the Nicobars once the war was over. Another threat was that of the possible interest of Prussia in the islands (Möller 1797:484).

The first attempt to colonise the Nicobars

The man chosen to lead this first Danish expedition to the Nicobars was Lt. Tang (Möller 1797:485).[2] Lt. Tang was considered to be one of the best, most hardworking and ambitious of the younger people of the company (Struwe, 1967:261). The instructions given to him were unambiguous. On arriving at t islands, he must follow a policy of appeasement and not conflict. It should appear to the natives that the purpose of their arrival was to repair the ships al to engage in trade. Going ashore must only be a consequence of an invitation by the natives (Möller 1797:485). With these instructions, the expedition led by Lt. Tang set sail on 5 September 1755 from Tranquebar. The total expedition of 81 members set sail on two ships: the King of Denmark under Capt. Bagge, and the Ebenezer under Capt. Gronberg (Möller 1797:485).[3]

2 Prahl (1804) refers to him as Captain Thanck and Struwe (1967) as Lt. Tanck.

3 Besides Lt. Tang, Capt. Bagge and Capt. Grönberg, there were another captain and a sergeant, one corporal, twelve soldiers, two blacksmiths, two carpenters, two masons, two kiln workers, two sawmill workers, 10 coolies, one material writer, one assistant to writer. In addition, there were some members recruited from the troops of the king already at Tranquebar. They were one Lt. Baron Tanner, one sergeant, one corporal, one tambour, 36 soldiers and one doctor by the name of Silchmöller (Möller 1797:485). Struwe (1967:265) lists some of the things they brought with them, such as cupboards, a writing desk and other furniture, silver teap' and sugar bowls, artificial hair, a coffee grinder, iron, porcelain, etc.).

The mission was shrouded in great secrecy and care was taken even wh, hiring the soldiers. Nonetheless, the news of the expedition reached the Engli and the French but apparently that had no consequences (Moller 1797 :51: After sailing for twelve days, the expedition sighted the southern-most island Schambelong (now called Great Nicobar) on 17 September 1755. Bad weather conditions, however, drove them to Achin from where they first arrived and anchored at Great Nicobar on 12 December 1755. On sighting the ship, the natives canoed towards them to barter food in exchange for tobacco and blue linen. Interpreting this as a sign of friendliness, the expedition landed ashore and, immediately after examining the coast, started to fell trees for the construction of a store house (Möller 1797:486).

The Nicobar islands were declared Danish property on 1 January 1756, and were re-named "New Denmark", according to instructions given to Lt. Tang (Struwe 1967:261). Celebrations and festivities followed that night, incorporating soldiers, guns and wine. Present at the celebrations were some 16 to 20 natives as well, who were informed - in Portuguese - that the islands now belonged to Denmark and not to Portugal anymore, upon which they were expected to raise their glasses of wine to the health of the Danish King (Möller 1797:487). From Danish accounts, it appears that there was no resistance from the natives in any way except that "the whole day ended in rejoicing" (Möller 1797:487). A couple of weeks later the two ships left for Tranquebar carrying with them a letter from Lt. Tang. Besides the news of their success, the letter provided a brief zoological and botanical description of Great Nicobar, and some ethnographic information concerning the inhabitants and local trade.

In the weeks that followed, the colonists continued clearing the forest for the purpose of a settlement. At the same time, they traded with the Nicobarese and obtained a cargo of coconuts for the next vessel. But their initial excitement was not to last long. Illness gripped the infant colony and in only a couple of months after their arrival, several of the members became ill and died. A month later, Lt. Tang too suffered a bout of the dangerous illness (referred to in most literature of the period as "Nicobar-fever"[4]. Further, disagreements between him and Lt. Tanner had done nothing to improve the situation (Meller 1797:491). At about this time, an English ship arrived to trade in arecanuts with the natives. Having finished their business, the English ship proceeded to Nancowry - a journey of about 24 hours - for further trade. Since the health situation in the colony was rather bleak, Lt. Tang saw this as an opportunity to search for a healthier place for their colony (Meller 1797 :491). Arrangements were made with the English vessel that one of the Danes, Steerman Panck, would accompany them to Nancowry (Prahl 1804:67).

4 Nowadays the fever would clearly be diagnosed as malaria. While the association of malaria with swamps, stagnant water, sultry air and high humidity was recognised long before, it was not until 1897-98 that the role of mosquitoes in transmitting the sickness was understood.

The report from Nancowry was promising, revealing the islands to be rich in pigs, chickens, coconuts and arecanuts and a hundred percent profit in local trade. Panck had observed that the English ship bought 100 areca-nuts for one large or two damaged leaves of tobacco; for half an elbow of iron - a full elbow was a length from wrist to elbow - the natives offered between 1,500 and 2,000 arecanuts; two armful of linen bought a pig; one piece of tobacco leaf bought one Yam; two or three leaves bought some juice from palm trees; tobacco leaf was the most highly prized by the inhabitants and one could sell small iron artefacts like knives, and linen. Additionally, there was the advantage of an excellent harbour, well sheltered from wind and easy to defend. Panck reported that the natives of Nancowry were very friendly and had asked him to stay on and trade (Möller 1797:493).

When the Ebenezer arrived from Tranquebar in March 1756 - bringing with it a new crew of six workers, 22 soldiers and thirteen slaves - Lt. Tang was prompted to write to the colonial government at Tranquebar for permission to move the colony to Nancowry. Governor Krog's reaction to the letter was positive. Not only was the permission granted to move to Nancowry, but Lt. Tang could also decide to move to Achin if an unhealthy climate prevailed, while retaining the Danish flag on Great Nicobar (Möller 1797:494). Unfortunately, before this move could take place, Lt. Tang and several others had died from illness. The Ebenezer stood at anchor with no-one to man the ship. When the vessel Copenhagen under Capt. Alling finally called upon the colony on 9 September 1756, the sole, and ailing survivor was Lt. Tanner (Möller 1797:495). The ship had brought an additional 150 people, along with a new colony leader by the name of Tycho Volquard (Struwe 1967:262).

According to the doctor on board, C.F. Silchllli'Jller, the illness was a result of warm days and cold nights experienced especially in the absence of proper housing. He also suspected that the fever might occur from the sultry air created by dense impenetrable forests and strongly recommended making clearings to allow the free movement of wind (Möller 1797:496).

So I have to witness what concerns the climate, that there is a sharp and sulphurous and heavy pennanent rain and marshy damps that stands between the high mountains that, during the day with the penetrating heat of the sun, lifts them up, and in the evening they fall again; that is the reason for the heated river-fever one can find here (Silchmöller, cited in Struwe 1967:262).[5]

5 "Saa maa jeg bevidne hvad kliman angaar, at den er skarp og svovelig og igennemtraengende formedelst standig vedvarende regn og sumpige dunster, som staar mellem de høje bjerge og om dagen ved solens penetrante hede den optraekker og om aftenen falder, da den er aarsag til den hidsige flodfeber, her forefalder."

A week later, the entire colony was moved to Nancowry. The inhabitants offered the Danes the chance to build their settlement in the place where the French missionaries had lived. Fearful that the French would come and claim their area, the Danes established themselves on the island of Kamorta, opposite Nancowry, because of its good soil, relatively few trees, and friendly people, who, it was reported, would easily agree to give their plantations for a small amount of linen (Möller 1797:498). The colonists immediately engaged themselves in felling trees to make clearings for the new colony. At the same time, they busied themselves procuring arecanuts from the natives as cargo for the next sailing to Tranquebar (Möller 1797:498). The settlement at Nancowry was, however, not an uneventful one. Following the departure of the Copenhagen to Achin for trade, several people fell ill and died. For several months, the survivors had no contact with Tranquebar and, in desperation, Capt. Alling left for Achin to find a means to get to Tranquebar (Möller 1797:499). Not long after the departure of Capt. Alling, Voquard died, further depriving the colony of an official leader (Struwe 1967:263). When the ship Ebenezer finally arrived, the stranded colonists had few reasons to rejoice. The new leader of the colony, Capt. Müller, had already died on board, which loss was followed by the deaths of several others including a missionary. Among the survivors was C.F. Lund, the trade assistant who then took over as the new leader of the colony (Möller 1797:500, Struwe 1967:263).

Following the King's order in December 1756, the Nicobar Islands were renamed as "Frederiks Islands" (Möller 1797:514), while Great Nicobar continued to be called "New Denmark" (Struwe 1967:262). The period under Lund was apparently a peaceful and an uneventful one, the colonists primarily engaged in felling trees and procuring a cargo of coconuts and arecanuts from the inhabitants to send by the next ship. Lund writes, "From the departure of the ship to the 12th of July I was living with my people fairly well without losing in all this time more than five men" (cited in Struwe 1967:263).[6] The colonial government of Tranquebar, however, was not content to have a trade assistant as the leader of a Danish colony. In July 1757, it assigned Capt. Jens Twed as the next leader. The arrival of Capt. Twed to take over as the leader of the Danish settlement led to a rivalry with Lund. However, this situation did not last long since Capt. Twed succumbed to the unknown illness and died just eighteen days after his arrival (Struwe 1967:264).

6 "Fra skibets afrejse ti112. juli levede jeg med mine folk temmelig vel uden at miste i al den tid mere end fern mand."

Once again, Lund assumed the leadership of the colony but the period that followed was far from peaceful. No longer satisfied with tobacco and linen, the natives started to demand that the colonists sell them weapons. The Danes protested about this request, following which the natives took to stealing from the company stores. Weak from illness, the Danes were unable to contain these incidents effectively (Möller 1797:500). In August 1757, riots broke out in the colony with hundreds of natives from surrounding islands coming together to lay siege to the colony and threatening to burn it down. Efforts to bring peace failed, and eventually Lund and his men had to flee to Achin (Möller 1797:501, Struwe 1967:264).[7]

7 It remains unclear how they went to Achin, whether on a ship they had or in canoes. Ml'!ller mentions that they went on board but then it is hard to understand why they went to Achin and not Tranquebar - probably the south west winds took them there - and why they later had to wait in Achin for half a year to go to Tranquebar - again probably waiting for the north-east winds.

Hereafter, according to Möller (1797:501), Lund and his men decided to go back to Kamorta and to retrieve what they owned. In January 1758, they sailed towards the Nicobars but misfortune overtook them as the ship's captain, in a state of alcoholism, crashed and sank the ship on the south coast of Nancowry. Mölller reports, "what the sea didn't take away was plundered by the Nicobarese"[8] (ibid.), referring to the materials on the ship. Most people, however, managed to swim ashore. According to Möller (1797:501), four of the survivors who reached the shore were murdered by the natives. Those left had to separate in order to search of food. Thereafter, there is no mention of what happened to those who ran off into the jungles looking for food and shelter, but Lund and his Indian servant lived on Nancowry - probably at the mercy of the natives - for fourteen months until an English ship took him first to Sumatra, then to Malacca and finally on 22 March 1760 to Tranquebar, bringing an end to the story of the first Danish attempt to colonise the Nicobars.[9]

8 "hvad Søen ikke borttog, det blev plyndretaf Nikobarerne."

9 Struwe (1967:264), however, provides a slightly different version of the first part of the story. According to this source, most of the colonists stranded on Achin found their way out over time to reach Tranquebar. Lund stayed back with some of his men until January 1758 until he obtained a ship to go to Tranquebar. On the way to ranquebar, the ship sank just near the former Danish establishment in Kamorta. None except Lund along with four of his men survived to reach the coast. While the four men were killed by the natives, Lund was spared out of pity. He lived for 14 months with his Indian servant, and finally on 14 April 1759 found a foreign ship to get way from the islands, reaching Tranquebar after a long journey in March 1760.

The second attempt at colonising

The connection between the Nicobar Islands and Tranquebar, however, was not yet over. The motivation for yet another attempt was somehow initiated by the Moravian missionaries.[10] A]ready in 1758, the King had in some way conveyed his interest to the Moravian brothers in establishing a mission on the Nicobar Islands (Latrobe 1812:6). As a result, an intense exchange of letters between the mission headquarters at Herrenhut, the Director of the Asiatic company in Copenhagen and Count Zinsendorf took place (Prahl 1804:73). After much correspondence, the mission finally received the privilege of the King and the first Moravian missionaries[11] arrived at Tranquebar in July 1760 (Latrobe 1812:7). At Tranquebar, a settlement named "The Brethren's Garden" was established to facilitate their work on the islands (Latrobe 1812:8).[12]

10 The Moravian missionaries belong to the Church of the United Brethren (aso called Unity of Brethren from the Latin Unitas Fratrum by which the Moravian Church was first known). They are called Moravians because the church had its origins in Moravia and Bohemia in 1457. During the bloody Thirty Years War, the Moravian order was completely destroyed and dispersed by the Catholic King Ferdinand in 1628. In 1727, under the patronage of Count Zinsendorf, a party of religious refugees formed the Renewed Church at Herrenhut that flourishes still today. The Renewed Unity's first foreign missionary programme was in 1732 among the African slaves of the West Indies.

11 George John Stahlman, Adam Gottlieb Völcker, and Christopher But]er (Latrobe 1812:7).

12 According to Prahl (1804), the missionaries arrived in India in 1759 and came to Tranquebar in 1768.

However, the recent failure to establish a permanent settlement on the Nicobars delayed the proposed mission work of the Moravians. It was not until 1768 that the Danish government at Tranquebar decided upon a second attempt to colonise the Nicobars (Möller 1797:502, Latrobe 1812:9) under the leadership of the Moravian Gottlieb Volker (Struwe 1967:265). The expedition set out on 7 August 1768 with six Moravian missionaries and twelve soldiers. Besides food for a entire year, they carried with them a wooden house ready to erect on the islands. The expedition arrived on Kamorta on 19 August 1768.[13] Except for a cannon ball, the Moravian brothers did not find any evidence of the first colony on Kamorta. Deciding against Kamorta, they chose Nancowry as the site for the second settlement. The Moravian brothers were of the opinion that the Nicobar fever had killed so many of their people due to the fact that they had lived close to the settlements. Consequently, they chose a place between the villages of Iconaga and Malacca. The natives offered the land without any payment since nobody actually owned it (Möller 1797:503). Later, in December 1774, a written treaty between the missionaries and the chief of Malacca ensured legal possession of the land where the settlement stood. Henceforth, the settlement was termed by the natives Tripjet (dwelling of friends) or Baju Tripjet (natives at Tripjet) (Haensel 1812:60).

13 In another version, Blumhardt (1845), a Moravian, reports that the first missionaries to arrive in India were five instead of three, the other two being Adam and Gottleib. According to him, the missionaries had already proceeded to the Nicobars in 1759 but were soon forced to abandon the settlement in 1760 since "scarcely ever had any mission to encounter so many privations and hardships of every kind, while the inhabitants continued quite unimpressible" (p. 130).

At the end of the year when the monsoons were over, illness gripped the colony and took the lives of the doctor and two of the missionaries (Möller 1797:503). The brothers by now had constructed their houses and had established a garden from which they obtained their own fresh vegetables. In September 1769, 24 new people arrived from Tranquebar at Nancowry under Capt. Falk, some of whom later deserted the colony and went to the Maldives on a passing ship soon after their arrival (Möller 1797:504, Prahl 1804:76). Death knocked at the colony's door once again, and within about four months, six people - among them Capt. Falk - had already died. All except two people were ill and bed-ridden (Möller 1797:505).

For the next three years, the colony was left all by itself with no ship or new people arriving from Tranquebar. The Danish Asiatic Company claimed that they did not have enough money to maintain the colony and intended to call their surviving employees back. With no Danish ships coming to the islands, the trade run by the brothers was seriously affected and lack of provisions reached a point of crisis. This led to the selling of accumulated sacks of areca-nuts to foreign vessels - mainly those belonging to the English - at low prices, giving them an advantage over other trade in the islands (M0ller 1797:506).[14]

14 Möller (1797:506) notes that for a sack of arecanuts they received only ten rupees.

By 1771, only ten people (including four brothers) comprised the entire establishment. But the courage of those few deserves admiration. In only a year, they had constructed a large open store house and a shed for animals, repaired the roofs and walls of their own residences, built a wooden floor, dug their first well that brought them better water than that collected from the rain, and successfully planted wine, the harvest of which was later sent to Tranquebar (Möller 1797:507). But their hard labour was not rewarded. In 1772, the Asiatic Company finally announced their intention to abandon the colony and called their employees back to Tranquebar (Möller 1797:508, Rasch 1967:375, Prahl 1804:77). Five years later, in 1777, the responsibility of administering the Danish colonies in India was taken over from the Asiatic Company by the Crown itself (Feldbraek 1991:8).

Following the withdrawal of the company's employees from the Nicobars, only a few Moravian brothers were left there to fend for themselves. The only support they received from the Tranquebar government was an irregular supply of cheap food and free transportation. Due to the irregularity of supply, provisions were always scarce (Möller 1797:508). In order to overcome this problem of food scarcity, the Moravians decided to charter a vessel owned by an Englishman, a Mr. Holford, based at Tanquebar. Although the first attempt in 1775 was successful, the chartered vessel failed to reach the islands due to bad weather in the following two attempts made in 1776 and the idea had to be abandoned (Latrobe 1812:11). In 1778, food became further limited and more expensive as a result of eight vessels of different nations coming to trade in the islands (Möller 1797:509).

But the Moravian brothers were not to be disheartened. For the next five years, they carried on their mission work, planted food, and built houses of stone that arrived from Tranquebar sent by their mission headquarters (Möller 1797:508). During this period, the brothers had good success in planting cinnamon from Ceylon, cloves, pepper, coffee, cotton and several Indian fruits. Communication with the outside world was limited to an occasional exchange of missionaries from and to their headquarters at Tranquebar (Haensel 1812). In 1779, the chief of the Moravian mission at Tranquebar reported to the local Danish colonial government that the settlement in the Nicobars now had only four brothers who had survived living on the islands without any troubles with the natives. The report further mentions that they had managed to learn the native language and had had good success with missionary work. The establishment now consisted of some good stone houses and a big garden with some animals. A small amount of trade in coconut oil and toddy - which the brothers produced and sold to the Coromandel coast via foreign ships - took place (Möller 1797:508).

The motive behind the production of such a positive report was clear: to convince the Tranquebar government to crawl out of its shell of inactivity regarding the colony. The account of Haensel (1812:22) on the other hand provides a very different impression. Haensel admits in his letters several times to the "fruitless attempts to preach the gospel to the natives". To this he attributes several reasons among which the lack of proper knowledge of the native language is primary (ibid., 61). Next were scarcity of provisions, the Nicobar-fever and the immensely arduous conditions of the colony (ibid., 63).

Nicolas Fontana, passing these islands in May 1778, observed:

On the re-establishment of the company [Danish Asiatic Company] in 1768, another house was built on Soury [Nancowry] Island, which was in 1773, in like manner, ordered to be evacuated as useless to the company's interests; three or four European missionaries, with a view of making proselytes, remained behind, and have continued there ever since, but without effecting even the conversion of a single person; they collect, however, cocoanut oil, shells, and other natural curiosities, which they send annually to their brethren at Tranquebar (Fontana 1799; 150).

(see also Austria and the Nicobars)

The disinterest of the Danes in the Nicobars was soon known in Europe and the Austro-Hungarians wasted no time to seize this opportunity. On l June 1778, the frigate Joseph and Maria Theresia arrived with orders from the Roman Emperor (Austro-Hungarian) to occupy the Nicobar islands. The expedition was the result of a proposal made in 1774 by Dutchman William Bolts, who convinced the Austro-Hungarian Empress Maria Theresia to colonise the Nicobar Islands on the grounds of their ideal location and excellent harbour and thereby establish direct trade with East Asia (Novara 1858:197). William Bolts had been a former senior employee of the British East India Company. Owing to his alleged engagements in the private opium trade, he was dismissed from service, arrested and transported back to Europe. Bolts intended to return to India to regain possession of his property and hence used the Austrian service for this purpose (Kasper 2002:162). Accepting Bolts as an expert on Indian trading conditions, the Austrians became hopeful of a share in the East Asian trade (Kasper 1987:31).

Bolts was authorised to take into possession, "in the name of the Empress and her successors, all territories settlements and grounds which he might acquire from Indian Princes in favour of all subjects of the Empress disposed to carry on trade with India (Novara 1858:198). The expedition, under the command of the Austrian East India Company founded in 1775, sailed to India in 1776 (Kasper 1987:31). While Bolts occupied himself with trade and politics on the Indian sub-continent, the frigate Joseph and Maria Theresia was sent under Capt. Bennet to occupy the Nicobar Islands in 1778 (Kasper 1987:32). On arriving at the Nicobars, Capt. Bennet came ashore to meet the brothers and showed them the written orders from his immediate superior Chief-lieutenant William Bolts - who had stopped over on the Malabar coast - to take possession of the islands in the name of the Roman Emperor:[15]

... I give the authority in the name of the Roman emperor to take all the Nicobar islands into possession and everywhere it is suitable there should be planted the emperor's flag, especially on the first hand those four islands - Kamorta, Nancowry: Tricut and Katchal. I have certain and clear information that Denmark never will claim them and therefore the Nicobars have no owner, so take them in possession without hesitation; and because on some of the islands there are Moravian brothers, I give the order to you that after you have made an agreement with them to plant the emperor's flag or to take them in the emperor's possession tell them that they would get an annual salary because one can make use of them as care-takers since they know the place and they understand the language of the natives as far as trade and common things are concerned (Prahl 1804:80-81).[16]

15 In the meantime, Maria Theresia had died and her son Joseph II had succeeded her as the Emperor of the Austro-Hungarian empire (Novara 1858:202).

16 "Jeg befuldmregtiger dem I Hans Majestrets, den romerske Keisers Navn, at tage aIle Nicobameme I Besiddelse, og aIlevegne, hvor det skikker sig, at opsrette keiserligt Flag, i Srerdeleshed gaaer Eders 0jemeed for det f'JrSte ud paa de fir 0er: Kamorte, Nancowry, Tricut og Katsiol: Da jeg har viss og tilforladelige Efterretninger, at Danmark viI besatte sig dermed, og Nicobameme alstsaa ingen Herre har, saa tag De dem uden Betrenkning I Besiddelse; da der paa een af sisse 0er skal befinde sig nogle mrehriske Brodre, saa befaler jeg Dem herved, efter Aftale med Dem at opsrette det keiserlige Flag hos dem, og tage dem I keiserlig Beskyttelse, samt tillage forsikkre dem god arlig Gage, da man med Tiden kan bruge dem til Opsynsmrend med Nytte, saasom de ere erfame paa Stredet, og forstaae Nicobaremes Tungemaal, ssavidt som Handel og almindelige Ting betrreffer. "

Vociferous in expressing their allegiance to the Danish flag, the Moravian brothers protested against the Austrian occupation. They also refused to comply with the request of Bolts for one of them to come to the Malabar coast as a translator. Capt. Bennet insouciantly ignored their protest and set about following the instructions that were given to him. He chose a place on Kamorta where the Danish settlement had been several years ago. With the intention of eventually building large houses, gardens and streets, his men set about clearing the paths. On 12 July 1778, Capt. Bennet called together a meeting of seven natives from the neighbouring four islands and twelve Europeans as witnesses to sign the following contract:

We, the Underwritten Inhabitants of these islands of Souri, Nancavery, Tricutt and Catchowle, being sensible of the great advantages of civilization under the regular government of a Monarch capable of protecting and defending us do hereby most earnestly request of Her Imperial Majesty... to accept of the Sovereignty of these Islands and to take us under the protection of Her mild benign government.. .And we do hereby solemnly declare, that we will do our utmost endeavours to disclose and make known to Her Majesty and her Successors or those appointed by them to the Government of these Islands all treasons and traitorous conspiracies which we shall know to be against Her or any of them and that to the utmost of our powers we will support maintain and defend their Interests in everything that can have relation to their sacred persons, their possessions, the Imperial crown and dignity, or the good of their subjects... (cited in Kasper 2002:190).

Following the contract, the islands were declared under the rule of the Roman Emperor. Among those who were invited to the celebration was Joseph Blaschke, the senior of the Moravian brothers, to translate to the Nicobarese on the new situation and to convey to them the impression that the Austrians and the missionaries were not in disagreement (Möller 1797:511, Prahl 1804:82). The frigate left the islands on the 4 of September 1778 for the Coromandel coast leaving behind Gottfried Stahl as Resident with five European soldiers and four workers. Additionally, the new colony possessed defence equipment[17], seeds, seedlings of some fruits and vegetables, tools and draught animals such as homed-buffaloes and horses (Kasper 2002:192).

17 According to Prahl (1804), the frigate left behind eight cannons for defence.

The Moravian brothers protested to the chief of the Austrian establishment in Kamorta.[18] The protest reached Bolts in Madras who expressed surprise on hearing about it. To his knowledge, it was confirmed that the Danes had withdrawn from the Nicobars on the 8 August 1772 and that all employees of the Asiatic company had been called back to Tranquebar. The few Moravian brothers, according to him, were living on the islands at their own costs for mission work. Further, he argued that the islands were taken in peace and agreement and "all inhabitants of the four islands: Nancowry, Chauri, Tricut and Katchal had with one voice asked for to be taken as the Emperor's subject and under his highest protection"[19] (Prahl 1804:84).

18 Prahl (1804:84-85) however, questions the integrity of the Moravian brothers by citing a letter in which they welcomed the Austrians to the islands: "..especially we have been very happy about that your honesty wants to start an establishment on the Nicobars under the name of Emperor Joseph 11 and the Empress Maria Theresia. We are happy about this new neighbourand we wiJI live with this new coming government or director or people and if we could help them with good information, it would be our pleasuresigned by Joseph Blatschke, Dav. Libisch, Christ. Fried. Haine".

19 "Aile lndbyggere af de fire Øer, Nancowry, Sauvry, Tricut og Katchoul, havde eensstemmigen bedet, at man vilde antage dem, som Undersatter af Keiseren og under hans allerhøjeste Beskyttelse."

The interest of the Austrians in the Nicobars proved a stimulant for the Danes. The news of the Austrian occupation of the Nicobars led the Tranquebar government to send a protest note to Copenhagen on 19 March 1779. The letter condemned the occupation of the islands by the Austrians as illegal since the islands were Danish property (Möller 1797:511). The merchants association wrote to the King that the islands should be recovered, "not alone for the nation's honour but also for the nation's trade advantages" (Rasch 1967:375). A situation of conflict arose and investigations as to whether the Danish claims to the Nicobars were legal or not became necessary before any further action could be taken. The merchants further argued that the Austrian Foreign Minister had clearly instructed the Austrian company not to occupy other nation's possessions. The islands were in the first place taken into possession by the Danish Asiatic Company and, even after the company withdrew their employees from the islands, the Moravian brothers had continued to receive food provisions from the Danish settlement in Tranquebar. Furthermore, the Moravians had shown the Danish flag to the Austrians in 1778. In this sense, the islands were still Danish property and it would be completely justified to remove the Austrians without endangering diplomatic relations with them (Rasch 1967:375).

Having established their legal claim, the Danes sought not only to remove the Austrians from the islands but also to undertake a renewed attempt for using the islands more profitably. That it was possible to deal with the unhealthy climate had already been proved by the Moravian brothers. In 1781, the Danish warship Wagrain under Capt. Andreas Bille proceeded to the Nicobars with orders to remove the Austrians. However, due to bad weather, the warship failed to reach the islands. By 1783, only one Austrian was left and it was not until 1784 - when only four people comprised the Austrian establishment, among them an Indian and an Italian - that the ship Dansborg succeeded in removing them (Rasch 1967:376-377).

In the years that followed, the Moravian brothers continued to represent the Danish crown. The highest chief among the Nicobarese received from the Danes a symbol of their sovereignty: a stick with a silver button on which was inscribed the name of the King of Denmark. One of the brothers always officially held the post of "Danish Royal Resident", patented by the King (Haensel 1812:66).[20] Hence, besides missionary work, the Moravian brothers were somehow "obliged" as far as possible to protect the interest of the King and his property against foreigners and to ensure fair trading conditions in the islands. Haensel admits that the task was not easy in the face of intruding forces and that he "much regretted the necessity of holding the office, and doing the duty of a Resident," as he nearly lost his life twice in this endeavour (cf. Haensel 1812:76).[21]

20 Among those who held the post of "Resident" were, Gottlieb Volcker, Armedinger, Blaschke and finally Haensel (Haensel 1812:66).

21 Haensel narrates two incidents with Malays who opposed his authority on the islands and threatened to kill him if he did not stop interfering in their activities as well as intervening in their trade relations with the Nicobarese (Haensel 812:66-77).

The Moravians, however, could not maintain the colony by themselves. There was illness and several of them died. The situation became even more difficult for them when the only ship they had possessed in the preceding years was stolen by a pirate from the Isle de France (Prahl 1804:79). By 1787, only one brother was surviving on the island, who decided to return to Tranquebar the following year (Haensel 812:26, Rasch 1967:377). In a period of less than 20 years, of the 25 missionaries who had arrived on the Nicobars, eleven had died on the islands while another thirteen had died after returning to Tranquebar (Haensel 1812:26).[22]

22 The only surviving missionary was John Gottfried Haensel who lived long enough to write - at the persuasion of Bishop C. I. Latrobe - a sympathetic account of the missionaries' struggle in the Nicobar islands (cf. Haensel 1812).

Following the return of the last missionary and with no one to hold the Danish flag on the Nicobars, the colonial government at Tranquebar sent eight soldiers to defend the colony against foreigners (Haensel 1812:26). A new plan was formulated to make better use of the islands. The Danish Government in Copenhagen offered four years' of help - in the form of land and supplies - to Indians in Tranquebar who would voluntarily go to the Nicobars as part of the Danish establishment. By now, aware of the death-trap, the offer was received without any enthusiasm in Tranquebar and nothing came of it (Rasch 1967:375).

In October 1790, an officer of the British East India Company visited the Nicobars and noted the desolate state of affairs of the Danish settlement. He writes:

Went on shore to the establishments, but found no European there to support, with due parade, the King of Denmark's presumptive authority in the island. A country-born Dutch-descended Sergeant was commandant of the place, and had with him two mulatto soldiers, two sepoys, one artilleryman, and two caffre slaves - all, excepting the Negroes, in His Danish Majesty's pay. The whole duty required of them seemed to be to hoist a swallow-tailed Danish flag upon a bamboo pole; to take charge of three or four old ill-mounted, unserviceable iron guns and a few rounds of powder and ball, given them for the defence of the settlement and (the most difficult task of all) to preserve themselves from the pressing attacks of hunger and disease. Their habitation, a truly wretched one, was half eaten up by white-ants. It has at first only a thatched roof to cover it, which being out of repair, afforded them scarcely any shelter against the heavy and almost continual rains that vex these desolate regions. The poor people complained bitterly of their condition, and in particular of their being left like banished criminals with a bare subsistence, unconsoled by any of those little additional comforts and indulgences so dreary and unhealthy a situation entitles them to, and indeed gave us no great reason, wither by their language or appearance, to think very highly of the bounty or humanity of the Governor General at Tranquebar, who, to say the truth, seems to have no other end in keeping possession of this post than to exercise their exclusive right of dominion there in imitation of the surly and too common example of the cur in the fable (Topping 1855, cited in Novara 1858:205).

In 1791, a new expedition led by Priest Henning Munck Engelhart, with a keen personal interest in the natural sciences[23] and history, decided to re-establish the mission on the Nicobars. Unfortunately, very shortly after he arrived, he died on 12 April 1791 and was buried on Taraka in the Nicobars (Rasch 1967:377).

23 Combining theology and natural science figured rather prominently in this period wherein, for several theologians, the road to science was theology. For some theologians, Christianity was nothing more than a "moral glue" for society while their real dedication lay in scientific pursuits. Travelling to newly-discovered lands as a missionary to pursue scientific ambitions was not uncommon. Some of the prominent examples are Bishop Johan Gunnerus (1718-1773), Charles Darwin (1809-1882), and Parson Lars Levi Lrestadius (18001861) (Wallin-Weihe 1999:22).

In any case, now was not the best time for the Danes to concentrate on the Nicobars. The Asiatic Company was already failing to maintain their share in the Asian trade. Their trading scope had already shrunk in the mid-I770s from the Coromandel coast to Bengal, and during the War of American Independence, the extent of their trade was reduced to the Danish centre at Serampore alone. Finally, the wars in south India between the English and the Marathas in the 1780s created an extremely uncongenial environment for Danish trade.It took another ten years for the company directors in Copenhagen to draw appropriate conclusions from the trade situation and close their centre at Tranquebar in 1796 (Feldbraek 1991:13). Following the death of Engelhart in 1791, the only Danish presence on the islands were some soldiers. The Danish government, still determined to maintain lawful control over the Nicobars, continued to sacrifice its soldiers by sending new ones to replace the dead (Rasch 1967:377). Colebrooke observes:

The Danes have long maintained a small settlement at this place, which stands on the northernmost point of Nancowry, within the harbour. A sergeant and three or four soldiers, a few black slaves, and two rusty old pieces of ordnance, compose the whole of their establishment. They have here two houses, one of which, built entirely of wood, is their habitation; the other, formerly inhabited by their missionaries, serves now for a storehouse (Colebrooke 1799: 106).

Sometime between 1802 and 1805 when not a single Danish representative lived on the islands, there seems to have been a short-lived English settlement. Thereafter, in 1805, there arrived eight Danish soldiers and an officer, who maintained the settlement until the English came once again in 1807 (Rasch 1967:377). The Napoleonic war between Denmark and England in 1807 proved devastating for the Danes as by the end of the war in 1814, most of the Danish territories in India were under British occupation. The Nicobar Islands too were taken over by the British in 1807 but were abandoned in 1814 with the end of the war. Even after the war, trading became increasingly difficult in the face of the persistent English domination over trade and territories. As a result the Danish trading posts soon lost their importance (Wallin-Weihe 1999:75,127).

The third attempt to colonise the Nicobars

Forty years were to pass after the death of Priest Engelhart before the Danish Crown decided to support a new attempt at establishing a settlement on the Nicobars. In the 1820s, a Danish pastor by the name of David Rosen submitted a plan to Copenhagen wherein he "wished intensely that Denmark should own such a colony" and that he "burned with desire to contribute my [Rosen's] share towards the fulfilment of this goal..." (cited in Wallin-Weihe 1999:105). Implicitly, Rosen's own account exhibits a similar vision to that of the famous Sir James Raffles who founded Singapore.

Rosen had arrived in India in 1818 as a missionary appointed by the English Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge (SPCK) (Wallin-Weihe 1999:87,94). In the decade following his arrival in India, he served in several mission centres in South India until in 1830 he was finally called to Tranquebar by Governor Christensen. Following a series of critical comments in Copenhagen and Tranquebar, Rosen's plan to colonise the Nicobars had found approval in Copenhagen and the orders for its execution had arrived in Tranquebar on 4 March 1829. Originally planned as a private enterprise, Rosen was unhappy with the changes made to the plan, especially the fact that the entire enterprise would be supervised from Tranquebar (Wallin-Weihe 1999:142). It comes as no coincidence that those plans proposed by missionaries found more favour with the Crown, while others such as Kroon (1785), Moller (1797) and Prahl (1804) probably never even received an audience with the King. According to Wallin-Weihe (1999:79), the Danish King was more positive towards missionaries than the Tranquebar government, which was, at best, lukewarm, and at worst, hostile to such plans.[24]

24 The first missionaries to arrive in Tranquebar were the Germans Bartholmreus Zigenbalg and Heinrich Pliitschau in 1706. Educated at the Pietistic University in Halle and ordained in Copenhagen, they arrived on their mission at Tranquebar with financial support from the Danish Crown. On their arrival, however, they were imprisoned by the Governor for a period of four months on the pretext that their presence could lead to public unrest. The relationship between missionaries and the colonial government developed into one of mutual acceptance in later years (Wallin-Weihe 1999:79).

The expedition of 31 members (excluding Governor Christensen, Rosen and a sergeant) arrived in the Nancowry harbour on 31 July 1831 on the schooner Cimbria, bought exclusively for this purpose.[25] On their arrival, the expedition made a show of arms and weapons but once ashore were met peacefully by the natives. One of these even showed them the stick with the silver button engraved with the initials "CVI" (Charles VI) that they had received from the Moravian missionaries as a sign of Danish sovereignty (Wallin- Weihe 1999:144). The site chosen for the new colony was apparently the same as that of the first Danish settlement in 1756, chosen later by the Austrians in 1778: a hilltop on the island of Kamorta overlooking the harbour and facing the village of Malacca on Nancowry island. Having arrived during the high monsoons, land clearing proved difficult and it took more than a month to eventually set up a pre-fabricated wooden house. Finally, in the middle of September, the initial work was over and the new colony was named "Fredrikshøi" (Wallin-Weihe 1999:145)..

25 The crew consisted of three carpenters, one barrel-maker, one blacksmith, one cook, twelve coolies and thirteen soldiers (Wallin-Weihe 1999:143).

Governor Christensen departed for Tranquebar on 22 September, leaving behind Rosen who now held the title of "Resident" of the colony. While work in the colony continued, Rosen busied himself meeting the native chiefs from the villages of "Malacca, Itoe,Inuang, Inuang, Eldegoang, Inega, Ulala, Teresa, Katsul and Bampok" and presented each of them a Danish flag, a piece of linen, some tobacco and a stick with silver buttons on which was engraved the name of the Danish King (Rosen 1839:28, 32). Not long after Christensen's departure, several of the colonists succumbed to illness and were not able to contribute to further construction work. Convinced of Fredrikshøi's unhealthy location, Rosen selected a new location on a hill on the eastern inlet of the harbour called Mongkata. It was believed that fever was caused due to still, sultry air and that Mongkata, owing to its altitude and exposure to winds, would be a more healthy place (Wallin-Weihe 1999:145). With most of his men bed-ridden, Rosen sought help from the natives in clearing the new location and in planting food such as coconut trees, and bananas for the colony. Fortunately for Rosen, some 200 survivors from an Indian ship that was wrecked near Great Nicobar arrived at Nancowry. Some oft hese Indians were employed by Rosen in the service of the colony as much-needed labour. But on the whole, the shipwreck itself contributed to a more serious problem. The natives had accumulated so much tobacco and cloth from the cargo of this stranded ship that, for the next two years, they refused to trade with the colony (Rosen 1839:40). Food became difficult to obtain from the natives and when they agreed to trade at all, the prices were exorbitant (Rosen 1839:56).

Relief came when, in December, the schooner arrived from Tranquebar with fresh supplies and additional men - including a sergeant and a doctor. The colony was now divided into two parts. Fredrikshøi functioned as a hospital for the sick, while Mongkata remained the main administrative centre. In the middle of January 1832, Rosen himself became sick and although he recovered, he never completely regained his health (Wallin-Weihe 1999:146).

|

|

Figure 6.1. Ground map of the Danish Colony, Kamorta Island (Source: From the book of David Rosen, 1839) |

On 15 April 1832, a dramatic incident occurred on the arrival of Governor Christensen from Tranquebar. While honouring his arrival with gunshots, a bullet hit one of the wooden houses at Fredrikshei and burnt everything down: the losses included all provisions, trading articles and, to Rosen's despair, all the notes that he had kept since his arrival in India. "But what hurt me most was the loss of all documents, of all my notes the whole time from my arrival in India..." (cited in Wallin-Weihe 1999:146).

Nevertheless, the accumulation of more manpower and administrative positions added prestige to the colony. Mongkata continued to be developed, and the construction of a road to connect the harbour to Mongkata began. The dense tropical forests, however, made it extremely hard for their objectives to be met and the whole enterprise had to be dropped. Rosen occupied himself with the continuing development of the colony, which included making clearings, erecting and maintaining new buildings, planting food for the colony as well as other crops for trade, collecting articles of trade from the natives, and though of least importance, policing the islands was highly symbolic (Wallin-Weihe 1999:147).

While Mongkata was still being developed, Rosen was toying with yet another of his ideas. He argued that Christensen should permit him to move the colony to Car Nicobar, the northernmost island in the Nicobars. Being a flat, forest-less island and hence healthier, and with many ships calling on it for replenishment of food, water and coconuts, Car Nicobar appeared an ideally central location for a successful colony. The Governor found Rosen's plans agreeable and permitted the move once the schooner returned from Tranquebar.

Figure 6.2. The Danish Settlement, Kamorta Island (1831- 1834) (Source: From the book of David Rosen 1839)

Unfortunately, this visit to the colony was to be Christensen's last voyage. On the way back in May 1832, Christensen died of fever, among many others (Wallin-Weihe 1999:148).

The schooner returned from Tranquebar in July 1832, and two weeks later, a team of about 25 people set sail for Car Nicobar, an island about 80 nautical miles north of Nancowry. What followed was a complete series of navigational errors and after a long voyage with several dead, the schooner arrived somewhere on the west coast of present-day Burma. Rosen himself writes:

If it exists a hard test for human patience. it is to see an easily achieved target disappear when it is nearly achieved. The travel to Car Nicobar gave me reasons enough to complain about my unfortunate fate. How could I have imagined that a trip we thought would take 24 hours...should be lengthened to 5 weeks and 4 days sailing in the Bay of Bengal. and that the goal of the expedition should not be achieved (cited in WalIin-Weihe 1999:148).

Not ready to give up his search for a healthier place, Rosen next decided to try the islands of Teressa and Bompoka. But after a short trip to those islands, he decided against them. The next choice was Trinket, an island that blocks the Nancowry harbour from the eastern side.

The island of Trinket was by now the only place I thought was left for us to chose. It was close by the harbour and had an open-field like terrain with less forest (Rosen 1839, cited in Wallin-Weihe 1999:149).

The move to Trinket, however, met with resistance from the natives, probably, in Rosen's opinion, because they feared that the colony might adversely affect the existing plantations belonging to them. But Rosen was detennined to find a healthier place as a matter of survival. Warnings from the natives about devils and insects on Trinket were transfonned into confrontation.

Finally at II p.m., when we were half way between Camorta and Trinket, they [the natives] declared that they did not want to row any more, and wanted to borrow our canoe against a promise of returning the next morning. I refused positively. They behaved like they accepted, but after a while the headman gave them a signal. Some of them jumped down in the canoe and the other made signs to take it by force. I ordered the siphais [soldiers] to threaten them with their guns and said that I would order them to shoot if they did not leave the canoe. This resulted in them starting to row again so that we later in the night reached our destination. I did not later notice that they had any grudge against us for the harsh treatment I had given them. A treatment that the conditions made necessary (Rosen 1839, cited in Wallin-Weihe 1999:169).

But the natives were right. Rosen (1839:95) provides a long description of the notorious flies and mosquitoes of Trinket which forced the colony back to Kamorta, this time settling themselves below the hill of Mongkata. Rosen notes that the natives were now more co-operative and forthcoming in helping to clear the new location. Somehow it seems that they must have heaved a sigh of relief to have the colony move back from Trinket. The new location was named "Fredrikshavn" on 10 April 1833 and was soon planted with coconuts, arecanuts, yams, mulberries and bananas (Rosen 1839:151). With no place to go, Rosen turned his attentions to the construction of brick buildings that would protect them from the climate and keep them healthier. But here, too, the colonists' efforts were not rewarded.

The importance of building was more and more evident as we could see how the high humidity and rain destroyed our dwellings. So far we had buildings made of wood. We needed the comfort of buildings that could withstand the weather and stay dry and safe. In addition came the danger of fire, burglary or enemy attacks. Everything suggested we should give the work of erecting buildings high priority. However our ability did not correspond to our motivation. Above all, the production of bricks turned out to be the worst obstacle. (Rosen 1839:151).

Already in 1833, Rosen felt that regular supplies to the colony from Tranquebar were diminishing. Tranquebar must have faced difficulties finding soldiers ready to go to the Nicobar Islands on an undertaking that seemed more or less like a death sentence. Already in 1787, Tranquebar had experienced a near-mutiny of soldiers upon hearing of a plan to transfer some of them to the Nicobar Islands (Struwe 1967 in Wallin-Weihe 1999:127). In the space of just one year, the colony had cost the Crown a great deal of money and people and there appeared no signs of returns. The second half of 1833 found the colony in desperate need of provisions, especially rice. When the schooner returned to the colony at the end of January 1834, there were spice plants and Chinese gardeners, but no rice. The colony faced a food crisis, the Indian workers withheld their labour, and the natives were not too enthusiastic about helping the colonists with food (Rosen 1839:128). The schooner did not return again until March 1834. But when it did, it brought much relief to the colony and work resumed. The Chinese gardeners had planted all of the nutmegs and cloves that had earlier arrived and rice cultivation seemed to be rather successful (Rose.n 1839: 155). However, there were unsuccessful attempts to establish a fishing place in the Malayan style (Rosen 1839: 156). With no tobacco leaves left, Rosen successfully issued vouchers to the natives in exchange of food, with a promise to honour them when further supplies arrived (Rosen 1839:157).

The return of the schooner on 13 June 1834, besides supplies, brought with it orders from Tranquebar to discontinue the colony, following instructions from Copenhagen. The reasons laid down were "lack of progress and great cost" (Wallin-Weihe 1999:153). Rosen was given half a year in which to close down the colony. But during this period, several of its members died and others fell ill while waiting to return to Tranquebar. As a result, Rosen could not achieve any of the work he had intended to do before ending the colony. Returning to Tranquebar, Rosen submitted two proposals to the Danish government: one for the continuation of the colony in the Nicobars, and the other for a free journey home, both of which were rejected (Wallin-Weihe 1999:153).

After Rosen's departure, the only significant European activity in the Nicobar Islands, besides the ongoing trade, involved French missionaries who were primarily engaged in preaching the Gospel. Prominent among these were two French clergymen sent by the Bishop of the Straits in 1835. They spent a year on Car Nicobar and established close relations with the Nicobarese such that, "they paid them frequent visits; bringing with them trifling presents, such as yams, fowls, etc., some of them anxious to learn the Christian religion went every evening to their house to be instructed: after a few months' residence there, the priest had gained so much affection of the people, that their house was crowded every day; and they were permitted to visit all the parts of the island without excepting even their inland establishments, where they keep their most valuable articles: a privilege which had never hitherto been granted to any foreigner" (Barbe 1847:18). However, this relationship of trust between the missionaries and the Nicobarese was damaged by reports spread by a Cholia vessel that the missionaries were actually English spies sent to investigate the available resources on the island, following whose visit the islands would soon be taken into possession. The rumour took root and the Nicobarese severed all ties with the missionaries who were advised to leave or else "they would become victims of their rage" (Barbe 1847:19).

Sometime in the middle of 1842, two other French missionaries by the name of Chopard and Borie arrived on Car Nicobar (Barbe 1847:19). It appears that the Car Nicobarese had not forgotten the past "betrayal" of the missionaries who had been among them six years ago and so the new missionaries were refused residence on their island (Busch 1845:14). The two missionaries therefore settled on Teressa and, though they had brought with them from Penang materials (as well as a carpenter and a gardener) for a house, were forced to reside in a local hut (Busch 1845:15). The Nicobarese were of the opinion that if a house was built which was different from their own, they would all inevitably die (Barbe 1847:17). Borie, however, died soon after his arrival on Teressa from fever and Chopard himself was forced to go to Mergui for a while to recover from illness (Chopard 1844:69). In the middle of 1844, Chopard was joined on Teressa by yet another missionary by the name of Plaissant (Busch 1845:23). Both Chopard and Plaissant, following long periods of illness, finally left the islands in May 1845 (Busch 1845:51).

In the three years spent in the islands, Chopard apparently developed good relations with the Nicobarese. The missionaries were visited by the islanders frequently. A school was even opened for the children although it was rarely attended (Barbe 1847:17), and Chopard himself admitted that they had not been successful in converting a single Nicobarese (Busch 1845:15). Barbe (1847) reports that the Nicobarese believed the French missionaries to possess powers like those of their menluana. The Nicobarese went to them on several occasions, saying:

Senhor Padre, give us some rain if you please; our yams are drying, we know you can do it if you like'. And on one occasion, the priest were threatened to be murdered if there was no rain. On the following day, fortunately, a strong shower fell during the night, and the people thanked them most cordially. One of the clergy, being on board of their canoes in his way from Chowry to Teressa, the crew told him - 'Senhor Padre, some breeze if you please': sometime after the wind blowing a little fresh, 'basta', they cried, 'it is enough, do not give anymore of it, otherwise the boat will be capsized (Barbe 1847:6).[26]

26 Writing 50 years before, Fontana (1799:153) says that the Nicobarese "entertain the highest opinion of such as are able to read and write: they believe, that all Europeans, by this qualification only, are able to perform acts more than human, that the power of divination, controlling the winds and storms, and directing the appearance of the planets, is entirely at our [Europeans'] command" (emphasis in original). Perhaps the reference is more relevant to the Moravian missionaries than to all Europeans.

The last attempt to Christianise the islanders before the islands became British was in 1851, by the Moravian missionaries once again. Nothing is known of their stay except that they, too, were expelled from the islands. A small report on their expulsion was published in the Singapore Review, vol. ii by Captain Gardener who was apparently visiting the islands around that time:

Having converted a few natives, dispute arose between these and their heathen countrymen. They were of such a serious nature that it was determined to hold a general council of delegates from every village to consider a remedy for the evil. They came to the conclusion, that, as they had always lived in love and amity with each other before the arrival of the missionaries, with their strange story of the first woman stealing the orange, etc., the obvious remedy was to send them away. Accordingly, the missionaries were waited on, and told respectfully that they must leave at the first opportunity: that the natives were not to be joked with, and must be obeyed. The mission house was then burnt down, and a fence erected round the spot, inside which no native will step. It is unholy ground, they say, where the devil first landed; for, until the missionaries brought him with them, he had never been in the island, or knew where it was. I was told that a day is now set apart in the year when all the inhabitants assemble to drive the devil out of the island (cited in Kloss 1902:63).

The Final Attempt: The First Galathea Expedition 1845 - 1847

All was not yet lost. Perhaps many Danes still shared the dream of Möller, of Prahl, and of Rosen, to turn the Nicobars into a new Java, a centre for Danish trade that would bring prestige and prosperity to the nation. The desire to re-start the colony on the Nicobars was apparently still very much alive. The aim this time was no less than an attempt to revive the dream of Rosen, that is, to establish a Danish counterpart to the commercial centre of Singapore (Wolff 1967:79).[27] It was assumed that their previous failures were a consequence of half-hearted attempts and under-investment. That the Nicobar-fever was the main and persistent problem was not accepted until later (Rasch 1967:378). The letter of Danish King Christian VIII on 14 May 1845 to the Danish Royal Academy of Science and Letters thus begins:

We have decided to send the Corvette Galathea to the islands of the East Indies and, in particular, to the Nicobar Islands, over which We have sovereignty, to take a scientific survey of the natural resources of the said islands and their viability for cultivation and trade... (Wolff 1967:70).

27 Singapore was founded in 1819 and in just a few decades had turned out to be an excellent investment (Wolff 1967:79).

Since the mid-eighteenth century, there had been an increasing interest in the natural sciences in Europe with the idea of "rationalism" central to the "Age of Enlightenment". Scientific enquiries and the study of ingenious adaptations of nature were undertaken and significant sections of the society (counts, bishops, civil servants, courtiers and merchants) were engaged in the collection of specimens, mainly shells, insects and minerals. A factor driving this development was the understanding of the significance of natural resources for the nation's economy (Wolff 1967:3). The scientific enquiries of the Galathea expedition were focused upon botany, zoology, geology, meteorology, marine and coastal surveys, and in particular corals (Bille 1852:8-13). Furthermore, continuous losses compelled Denmark to sell off all its remaining possessi<;ms on the Indian mainland, but retaining the Nicobar Islands. The English had halted all trade by placing a customs frontier around the Danish territory in Tranquebar (Wolf 1994:78). Hence, one of the objectives of the Galathea expedition was also to oversee the transfer of Danish settlements at Tranquebar and Frederiksnagore in India to the British East India Company. Combined naval and scientific expeditions such as the Galathea expedition were not unknown. Among others, the most famous had been the voyage of the Beagle in the 1830s upon which Charles Darwin laid the foundation of his The Origin of Species (Wolff 1967:71).

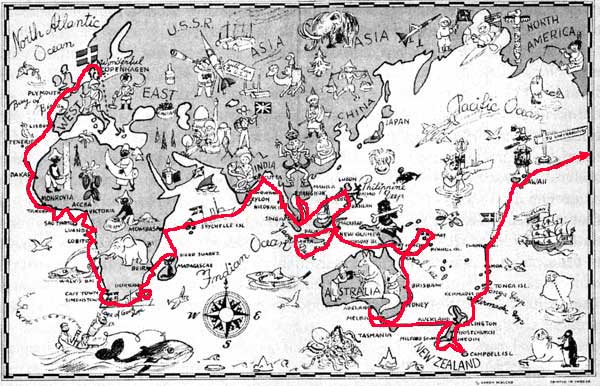

The commanding officer of the Galathea was Steen Andersen Bille, who was known for his wide experience and had for some time also been the Minister of Naval Affairs and a vice-admiral (Wolff 1967:74). Bille had received specific instructions: that his presence was essential while handing over the Danish territories in India to the British East India Company; to take into possession any territories he thought fit for the purpose; to install Danish representatives on the Nicobar Islands, but in the case of other Indian and Chinese territories he would have to consult Hansen, the Governor of the Danish territories in the East Indies (Bille 1852:8). The Galathea's two-year voyage around the world began on 24 June 1845. The Galathea sailed first to Madeira and then to Tranquebar, crossing the equator. After handing over the Danish territories of Tranquebar, the expedition proceeded to Madras and then to Calcutta, from where preparations were made to go to the Nicobar Islands (Bille 1852, Wolff 1967:77-79).

Figure 6.3. Route of the Galathea 1845-1847 (Courtesy Zoological Museum, University of Copenhagen)

Before the Galathea set sail for the Nicobars, the schooner L'espiégle under the command of Capt. Lewis (an Englishman) and H. Busch (a Dane), in charge of the expedition, had been sent to make a preliminary survey of the islands. The stated primary objectives of this smaller expedition were to search for coal in the southern islands and to undertake a marine survey of the sea (Busch 1845:10). However, Busch's Journal of a Cruise amongst the Nicobar Islands (1845) reveals that they also engaged in collecting samples of birds, reptiles, mammals, fishes, etc. as collections of natural history (p. 58-60), and even took into possession some of the islands under the name of the Danish King (p. 46-49). Bille (1852:13) mentions yet another objective, to establish a warehouse for coal on the island of Great Nicobar. However, there is no indication of this as such from Busch's account. Besides their partial success in their search for coal in the southern islands and a survey of the sea, the expedition took into possession the islands of Kondul and Little Nicobar, and a certificate was issued to the headmen ofthe two islands bearing the following:

To all persons who may visit the islands of Pulo Condul and Great Nicobar, we do hereby certify that having this day [5 May 1845] hoisted the Danish Ensign on these two islands, we have resumed possession there of in the name of his Danish Majesty, King Christian the Eighth: we have entrusted the flag to the Headman of Puloo Condul, by name of Tamarra, in order that he may guard the same until further measures can be taken, for the contemplated occupation and colonization of the said islands... (Busch 1845:55).

Within a period of two months, the L'espiégle sailed to nearly all the islands in the Nicobars, returning to Calcutta at the end of May 1845. According to Steen Bille (1852:181), the expedition undertaken by the L'espiégle had little success owing to the lack of manpower and equipment on board. However, themaps made by the expedition were amongst the best available for the Galathea to use in their voyage to the Nicobars (Bille 1852:182).