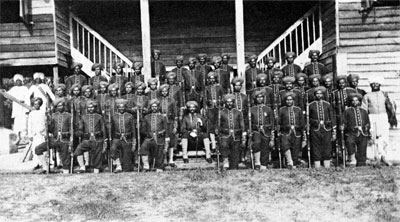

Figure 7.1. Madras Infantry, Nancowry Islands (ca.

1900)

(Courtesy Museum fur Volkerkunde, Vienna)

The Nicobar Islands

The British in the Nicobars

by Dr. Simron Jit Singh

|

Table of Contents

The occupation of the Nicobars The Nancowry penal settlement (1869-1888) The colonial period (1888-1947) |

|

The following text was originally published as Chapter 7 (pp. 197-220 and 227-241) of S.J. Singh's In the Sea of Influence - a world system perspective of the Nicobar Islands, Lund Studies in Human Ecology 6, Lund University, Sweden, 2003, ISBN 91-628-5854-8, ISSN 1403-5022. Copyright ©2003 Simron Jit Singh Footnotes are marked in the text with square brackets [ ] and can be found at the end of the following paragraph. For references mentioned in the text consult the printed book. |

In the second half of the eighteenth century, following their historic victory at the Battle of Plassey in 1757, the British were on the way to becoming a territorial power in India as the Dutch had already become in Java. Operating between Surat and Bengal, the Calcutta fleet of the British "country traders" slowly edged the big Indian shippers out of the maritime business there. The policy of merging trade with conquest thrust itself eastward towards the coast of China, breaking through the Dutch enclosure in the Malay-Indonesian archipelago. The establishment of Penang in 1786, the founding of Singapore in 1819 and the acquisition of Burma through the wars of 1826, 1852 and 1885 eventually saw the Bay of Bengal being encircled by a single British empire (Gupta 1994:43-44).

The extension of the British empire towards the east raised the question of a safe harbour for the British fleet during the monsoon months. Islands close to the coast were not preferred, since there was the likelihood of conflict with the inhabitants. A cursory survey of the Andaman Islands by John Ritchie in 1777 induced the British Government to consider them for the purpose at hand (Mathur 1968:44). The Andaman Islands, situated right in the middle of the Bay of Bengal and at a convenient distance from British headquarters in Calcutta and Rangoon, were looked upon as providing a potential solution to the problem of a safe shelter for the British fleets during monsoons. In 1788, a detailed survey of these islands was commissioned under Lt. Archibald Blair. A site was selected and a year later, Blair returned with 200 Indian volunteers wishing to settle there. However, the war with France in 1793 raised the question of security of the little colony. Fortification efforts were made with some prisoners brought from Calcutta but bad weather conditions together with malaria cost many lives. By 1796, the situation became un-manageable and the colony had to be abandoned (Tamta 1991: I 0-11).

Once again, in 1857, the question of colonising the Andamans was raised. This time the need was different and even more pressing. The uprising by Indians against British rule in 1857 threatened the very foundation of the Britishempire in India. When the crisis was finally brought under control, it became imperative for the British to find a suitable place in which to keep the revolutionaries far from contact with the masses. For this purpose, the use of the Andaman Islands was once again brought under consideration. A commission under Frederick Mouate was asked to survey the islands with a view to establish a Penal Settlement. The outcome was positive and on 22 January 1858, the Penal Settlement was formally inaugurated with the hoisting of the British flag. The first batch of 500 prisoners arrived at these islands on 10 March 1858 (Tamta 1991:12). The Penal Settlement was under the charge of a Superintendent. The story of the Settlement is one of tortures and soul-crushing labour but that is not the subject of this monograph.[1] One major impediment to the Settlement was conflict with the aboriginals inhabiting the greater part of the islands. These were the Great Andamanese, the Jarawas, the Onges and the Sentinelese. Of these four groups, the first two were most problematic to the British as their territories were closest to the Settlement. Violent clashes often took place, with deaths on both sides. The prisoners were most vulnerable to the arrows used by aboriginals since they remained largely unprotected and had to venture out to clear the jungles. However, over time, the British managed to subdue the Great Andamanese during armed conflicts, capturing them when possible and keeping them in special homes they had set up in which to "civilise" them (Mathur 1968).[2]

1 The story of the Penal Settlement is well documented by Mouate (1863) and Mathur (1968).

2 Of the estimated 5,000 Great Andamanese at the time of British occupation, their population today is less than 30 who live protected on the 6 km2 Strait island in the Andamans (Andrews & Sankaran 2002:41). A detailed account of the relationship between the British and the Andamanese aboriginals is provided by Portman (1899) and more recently by Mathur (1968).

Until 1869, the Penal Settlement was under the administration of the Chief Commissioner of Burma, after which it was brought directly under the colonial Government of India. In 1872, the designation of "Jail Superintendent" was changed to "Chief Commissioner of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands" (Mathur 1968:138)[3]. By 1874, the Penal Settlement had grown considerably and contained 7,820 men and 895 women prisoners undergoing life imprisonment. Some 824 acres of forest had been cleared by the prisoners, of which 405 acres were used for agriculture. Ross Island served as the administrative headquarters, with palatial houses, church, club, playing ground for cricket, tennis, golf, swimming pools, etc. for British officers (Tamta 1991:21).

3 The title of "Chief Commissioner" was only created for judicial reasons while the title "Superintendent" continued to be used in official correspondence (Mathur 1968: 138).

The increase in the number of prisoners made it difficult for the jail staff to enforce control and discipline (Tamta 1991:21). In 1890, a committee under Sir Charles Lyall and Alfred Lethbridge recommended the construction of the Cellular Jail and enforcement of strict discipline (Tamta 1991 :25). The construction of the Cellular Jail began in 1896 and was completed in 1906. The Jail had 698 cells and provided the possibility of isolating prisoners for a period of time. R.C. Temple, Chief Commissioner of the islands, writes with respect to the life of the convicts there:

The life convicts are received into the Cellular Jail for six months, where the discipline is of the severest, but the work is not hard. They are then transferred to the Associated Jail for 18 months, where the work is hard, but the discipline less irksome. For the next three years, the life convict lives in barracks, locked up at night, and goes out to labour under supervision. For his labour he receives no reward, but his capabilities are studied. During the next five years he remains a labouring convict, but is eligible for the petty posts of supervision and the easier forms of labour; he also gets a very smalJ allowance for little luxuries, or to save in the special Savings Bank. He has now completed ten years in transportation and can receive a ticket-of-leave (self-supporter). In this condition he earns his own living in a village: he can fann, keep cattle, and marry or send for his family. But he is not free, has no civil rights, and cannot leave the Settlement or be idle. After 20 to 25 years spent in the Settlement with approved conduct, he may be absolutely released. While a self-supporter, he is at first assisted with house, food, and tools, and pays no taxes or cesses, but after three to four years, according to certain conditions, he receives no assistance and is charged with every public payment, which would be demanded of him, were he a free man. (Temple 1903:354).

Once intense discussions were underway to abolish the Penal Settlement, the British Government finally preferred to colonise and develop the islands through the agency of an enlarged population of ex-convicts and their families. The population in the Andamans, originating with these self-supporters, continued to increase in the following decades (Mathur 1968:147-148).

The occupation of the Nicobars

The Nicobar Islands, lying between the sixth and tenth degrees of north latitude, have for sometime attracted very much the attention of the public in India, not so much on account of the productive qualities of their soil, but because of the islanders having committed repeated murders on the crews of several vessels under the British Flag. Vessels sailing from the Coast or from Penang have, for long period of years, touched there during the NE monsoon to take a cargo of cocoanuts.. .Not a single year has passed without hearing of some vessels or boats being lost (Barbe 1847: I; my emphasis ).

In the period between 1848 and 1869, the Nicobar Islands remained theoretically without an "owner". Despite Franz Maurer's advice to the Prussian (German) Government in 1867 to colonise the islands (Temple 1903:186), not much seems to have happened in this direction. During this period, however, piratical activities, particularly in the region comprising the Central Nicobars, seem to have increased greatly.[4] It would, nonetheless, be far-fetched to associate the rise of piracy with the absence of a European "owner" for the islands. Piracy in these seas were not unknown before 1848. The brief "occupation" ofthe Nicobars by Dutch pirates in the eighteenth century is noted by the Indian historian Gupta (1994:47). Rosen (1839) describes Malay pirates as one of the threats to the Danish colony (Wallin-Weihe 1999:152).

4 Between 1837 to 1869 some 26 vessels are believed to have been plundered and the crews massacred (Man 1903: 188).

However, the first descriptive accounts of assaults on vessels is provided by Busch (1845:16-18), whose information is based on the reports ofthe French missionaries then living on Teressa island. The first reported incident concerned the plunder and massacre of the crew of a Chulia vessel in 1833 that had anchored in the Nancowry harbour. But no notice seemed to have been taken of this. The vessel Pilot met with a similar fate in 1839. The cause, in this case, was attributed to provocation arising out of interference with the Nicobarese women. Nonetheless, a year later, the British Government sent a vessel in retaliation and "burned a few huts, fired some shots, and punished the innocent with the guilty" (Busch 1845: 17). The third incident took place in 1844 off the coast of Teressa to the vessel Mary. "The captain was killed on the quarter-deck whilst bargaining with the natives, whereupon the crew leapt overboard and were drowned or murdered, the vessel was plundered, and then set fire to and turned adrift" (Busch 1845: 17). The following year, the British Government sent a war steamer to make enquiries but, perhaps owing to the lack of any evidence pointing towards the guilty, no retaliatory measures were taken. In 1844 again, a second incident took place concerning a vessel owned and commanded by Capt. Caw. While most of the crew were either killed or leapt overboard, an Arab, who had the presence of mind to defend himself with firearms, then brought the vessel to Penang single-handed. Once again, a vessel of war was sent to make enquiries, but "nothing further appears to have been elicited" (Busch 1845:18). Some years later, in 1852, the debate on piracy once again emerged in British correspondence, the cause being two British vessels plundered and the crew massacred in the Central Nicobars (Official Correspondence 1852-1869:264-267).[5] The vessel Steamer was sent under Capt. Dicey to make investigations of the case but nothing concrete surfaced except the knowledge that the principle suspect was a Malay. Besides this, a few articles that apparently belonged to the attacked vessels were found in some houses and were confiscated (Official Correspondence 1852-1869:268).

5 The full citation to these documents is, "Official Correspondences ultimately leading to possession being taken of the Nicobars by Her Majesty's Indian Government" in Selections from the Records of the Government of India, Vol. LXXVII - Papers Relating to Nicobar Islands, Calcutta, 1870.

Curiously, it became apparent that the majority of the vessels being scuttled were under the British flag (Barbe 1847: 1, Man 1903: 188) and "purely native craft, however, have never known to be attacked" (Busch 1845:18). For the first time, in 1856, it began to be argued that the occupation of the Nicobars and the establishment of a penal settlement was the only solution to controlling piracy in the region (Official Correspondence 1852-1869:271). Ten years later, in 1865, following a news item in the Englishman on piracy in the Nicobars, the same argument was once again put forward by Capt. Hopkinson to the British Government stating that, "Any project for the re-occupation of the Andamans should also comprehend arrangements for exercising from them a surveillance over the neighbouring group of Nicobars...It would be well if these islands could be reduced to our authority, and if the establishment of a penal settlement were the only consideration, they would probably answer as well for that purpose as the Andamans" (Official Correspondence 1852-1869:271).

The matter culminated in 1866 with the massacre off the coast of Trinket[6] of 21 crew members belonging to the British vessel Futteh Is/am (Official Correspondence 1852-1869:273-275). From the statement of the three survivors, it was evident that the assassins were mainly Malay (Official Correspondence 1852-1869:276). The episode, however, sparked off a lengthy discussion involving the highest authorities, which resolved to find a solution to the piracy in the Nicobars. The infuriated Chief Commissioner of British Burma, Col. Fytche, suggested that the most effective form of punishment would be the "destruction of the plantations of cocoanut trees in the vicinity of Malacca, and the village itself destroyed by fire; after which a notice on a white board, written in Malay character with black letters, should be attached to some tree, stating the cause of this demonstration" (Official Correspondence 1852-1869:281). He further argued for a penal settlement on Kamorta in the Central Nicobars as the island had good anchorage and was free from jungle with abundant water and good soil (Official Correspondence 1852-1869:282). The Governor General of British India responded by saying that "it has seldom been quite clear whether the islanders or the Malays were chiefly guilty... by destroying cocoanut trees, the islanders would be cut off from their source of food and traffic for some years. Thus an additional stimulus to piratical acts would be given by a retaliatory measure of this character... unless very clear proof be obtained that the village of Malacca is the offender, this mode of punishment will not be resorted to" (Ibid.). The Governor General further suggested that in the absence of definite proof as to which village was involved in this outrage, "the most effective measure would be a blockade of the four islands which compose the group, viz., Camorta, Trinkuttee, Nancowry, and Katchall, so as to cut them off for the space of a N.E. monsoon from all trade with the Malay or Burman coasts, informing the inhabitants, however, that on surrender of the perpetrators of this particular outrage, the blockade will be raised" (Official Correspondence 18521869:283).

6 Capt. Bedingfeld leading the investigation into this episode reports that the incident occurred on Great Nicobar at a place called Trinkuttee (Official Correspondence 1852-1869:292). However, the testimonies of those survived specifically refer to Trinkuttee as an island (Official Correspondence 1852-1869:275, 277). This leads to confusion as to the actual location of the incident.

An on-site enquiry into the matter was commissioned in 1867 under Capt. Bedingfeld and on the recommendations of his report, houses, canoes, poultry and pigs were destroyed in Great Nicobar and Nancowry islands (Official Correspondence 1852-1869:305-306). Also, Col. Henry Man was appointed to comment on the piratical activities in the Nicobar islands and to advise the colonial Government of India on future measures (Official Correspondence 1852-1869:288). Col. Man's advice to the government was straightforward: "the simplest and most effectual mode of doing so [suppressing piracy] is by taking possession of these islands" (Official Correspondence 1852-1869:301). Col. Man further argued that the Nicobars be made a dependency of.the Andaman settlement, and hence come under the jurisdiction of the Government of India:[7]

The Nicobars would, I think, form an important adjunct to the Andaman command, the Superintendent of which has, I am told, a gun-boat at his command, which could easily, with little interference with its special duties, and with benefit to the crew and vessel, pay periodical visits to these islands, and return, if need be, in 48 hours to its station (Official Correspondence 1852-1869:301-302).

7 There had been discussions whether the Nicobars should be attached to the Government of British India or to the Straits Government (Official Correspondence 1852-1869:288, 312).

Col. Man further argued that, in this way, an over-accumulation of convicts at the Port Blair Settlement could be prevented. A colony of convicts at Nancowry or Trinket could contribute economically to Port Blair by being "employed in collecting cocoanuts on Government or their own account, for the supply of shipping, and also in raising cattle, grain, grain, vegetables, &c." (Official Correspondence 1852-1869:302). Following this advice from Col. Man, there took place some correspondence between the Government in British India and in Britain. However, the annexation of the Nicobars as part of British India inspired protest on the part of the Duke of Buckingham who believed that:

... the best way to keep these people in order and prevent piracy, would be frequent visits by vessels-of-war, and full measure of punishment for any crimes committed. And this, can be much better done while these people are not British subjects than if the islands were annexed to any British territory, and the people thus endowed with privileges of British subjects (Official Correspondence 1852-1869:313-314).

To this the Government of British India argued that this mode of punishment had so far remained ineffectual. At this point, yet another argument for annexing the Nicobars to the British empire emerged, namely the danger of the occupation of these islands by a foreign power (Official Correspondence 1852-1869:315) and the "inconvenience as would be caused by the possible establishment of a rival foreign naval station in such proximity to our settlements in the Indian seas" (Man 1903: 189).

Apparently the new argument was strong enough for the plan to win approval. However, before the final assent could be given, Britain thought it wise to communicate their intention to Denmark's authorities to allow them to express any objections they might have. The Danish Government, in 1868, replied by saying that a "formal cession" of the islands was not considered advisable since the islands had been "derelict" since their abandonment. However, they had no objection to the Government of British India taking possession of the islands. But if the Government of British India so insisted, then the Danish Government "voluntarily cedes its rights over them to that of Her Britannic Majesty, on the understanding that no other power shall. have already taken possession of them" (Official Correspondence 1852-1869:315). In 1869, the occupation of the Nicobar Islands was finally endorsed by the Foreign Department of the Government of British India and a resolution was passed by the Home Department approving in full the scheme proposed by Co!. Henry Man. It was agreed that at first the actual occupation should concern the three islands of Nancowry, Kamorta and Trinket, these being the islands where most piratical acts had occurred, while extending a general protectorate to the other islands as well (Official Correspondence 1852-1869:316). The ship-of-war Spiteful, under the command of Arthur Morrell, set sail for Nancowry on 18 March 1869. On arrival, Commander Morrell selected a site for the flagstaff on the extreme northern point of Nancowry islands, which he called "Mayo Point". A proclamation (accompanied by firing a royal salute) was read on 27 March 1869 and re-read again on 16 April 1869, following an amendment by the Governor General "placing the islands under the control of the Indian instead of the Imperial Government, as was the case with the first" (Official Correspondence 1852-1869:320).[8]

8 The final proclamation that was read on 16 April 1869 was the following: "I, Arthur Morrell, a Commander in Her Britannic Majesty's Naval Service, and now Commanding Her Majesty's Ship-of-war Spiteful, having received instructions thereto from Commodore Sir Leopold Heath, K.C.B., Commanding Her Majesty's Naval Forces in the Indian seas, acting on the requisition of the Earl of Mayo, Viceroy and Governor General of India, do now on this the 16th day of April 1869 in the name and on behalf of the Indian Government of Her Majesty the Queen of Great Britain and Ireland take possession of this Island of Nancowry, together with all others commonly known as Nicobar Islands, that is to say, the Island of Car Nicobar and Great Nicobar with those lying between them including Tiliangchong, and in token thereof I now hoist the flag of Great Britain, proclaiming to all concerned the Supremacy of Her Most Gracious Majesty, declaring the said islands to be subject to Her Majesty's Indian Government, and calling upon the inhabitants of the said islands to submit themselves to Her Majesty's laws as administered by the Government of India" (Official Correspondence 1852-1869:317-318).

In preparation for the arrival of the colonists, the period from 24 March to 15 April 1869 was utilised to clear a large part of the jungle around Mayo Point, to deepen an old well and to sink a new one. With the arrival of Col. Man on 15 April 1869 in the vessel Arracan and towing along the hulk Blenheim[9] (Official Correspondence 1852-1869:320), the administration of the Nicobars became the responsibility of the Superintendent of the Andaman Settlement within the jurisdiction of the Chief Commissioner of British Burma (Official Correspondence 1852-1869:312-313). Two years later, in January 1871, the proclamation was re-read amidst the firing of royal salutes to the inhabitants of the northern and southern islands, it not having been formally made known elsewhere other than in the central Nicobars.

9 The hulk Blenheim served as a residence for British officers, and as a base for the new colonial establishment in the early period of occupation until the time when a more permanent infrastructure was ready for use on the islands.

The Nancowry penal settlement (1869 -1888)

Owing to the fact that most of the acts of piracy had been concentrated within a short radius of the harbour, the central Nicobars were a clear choice for the location of a settlement. Following possession, the first step was the establishment of a Penal Colony that would act as a dependency to the one in Port Blair, under its direct supervision. In June 1869, a site comprising 500 acres was picked on the southeastern part of the island of Kamorta, overlooking both entrances of the harbour.[10] The location thus chosen was seen to have an added advantage for the proposed cattle-breeding farm, since the area extending northwards was a grassland suitable for the purpose (Man 1903: 189). Although the new settlement was located on the island of Kamorta, a resolution of the Home Department in 1871 decided it should be called "Nan cowry Harbour Settlement" (Man 1903:189, Mathur 1968:286).

10 The site appears to be quite near or even identical to Rosen's Mongkata.

During the first five years of the initial construction phase of the penal settlement, that is until April 1874, the hulk of the East Indiaman vessel Blenheim anchored in the harbour was employed to accommodate the pioneering administrative staff and at times also served as a sanatorium for those requiring a respite from island life on account of illness The settlement was placed under the charge of the Assistant or Extra-Assistant Superintendent of the Port Blair establishment, who was invariably a European (Man 1903:189). During the nineteen years of the Nancowry Penal Settlement, the average population associated with it consisted of 350 members. These included two Europeans, two other officers, a garrison of 58 soldiers, 22 policemen, 35 free residents, and 235 convicts (Temple 1903:186).

The early batches of convicts to arrive at Nancowry were those who were only serving limited prison terms. Later when convicts serving life sentences began to arrive, the incidence of escape grew. In 1875, when limited-term convicts began to be sent once again, that consequently reduced the number of escapes (Mathur 1968 :286). It was discovered that the most difficult period of imprisonment in terms of health was the first year, after which the convicts became acclimatised and their productiveness increased. Therefore, unless recommended by the medical officer, the tenure for each convict was limited to three years, following which he was eligible for a transfer to Port Blair (Man 1903:189).

Construction work already started in June 1869, using the first batch of 262 convicts for the purpose (Mathur 1968:286). The major construction works in which the convicts were employed were buildings (for housing and administration), tanks, wells, metalled roads, drains, sea-walls, and. a jetty. Building materials comprised chiefly of timber, clay bricks, coral blocks and lalang (Imperata cylindrica) grass. Timber and other supplementary materials such as posts and bamboos were obtained from the neighbouring jungle. Planks of timber were produced at the local sawpit station in Octavia Bay. Roof material was the omni-present lalang grass which was invariably used by the Nicobarese for the same purpose. Bricks were manufactured using suitable clay available on the islands. In the absence of suitable stones for building purpose, corals were shaped into blocks and slabs using blunt axes and were satisfactorily used in the construction of reservoirs, wells, sea-walls and jetty (Man 1903:190).[11]

11 It was believed that exposed live corals were detrimental to humans in the vicinity. Hence, "the quarrying of the adjacent reefs and the utilization of the coral in the above manner [i.e. as construction blocks] thus served a double purpose" (Man 1903: 190).

A large part of the convict labour was utilised for the development and maintenance of the settlement in terms of constructing new buildings, structures, drainage system, roads, improving sanitation, etc. One of the major concerns faced by the new colonists, as by the previous ones, was malaria. Sickness was rampant, with an average infection rate of over 9% each year as compared to 7% at Port Blair. However, the early years were most difficult, with the sick rate going up to 12% despite all counter measures undertaken (Temple 1903: 187). The British administration had hoped to control malaria with similar methods as had been successfully employed at Port Blair, mainly that of improved sanitation. But while these measures to improve living conditions were being taken, the services of the mail steamer were used to rotate free residents and sick convicts "requiring a change of air" to Port Blair and back again on a regular basis (Man 1903: 189). In 1874, most of the convict labour was employed in the reclamation of swamps, particularly the one on the northeast side of the settlement known to be responsible for causing a high rate of sickness (Man 1903: 190). In 1876, however, before the reclamation of swamps was even half finished, the entire project was dropped and the sea was re-admitted as before. Two and a half years of intense work was abandoned for the following reasons:

1. the position of the sluice-gate fixed by the Public Works

Department was faulty;

2. labour was scarce and more could not be afforded from Port

Blair;

3. much sickness was occurring among the men engaged on the work,

and

4. the reclamation might prove of questionable utility.

(Man 1903:190)

Besides development work, the convicts were also employed in economic activities such as in the extraction of coconut oil, making oil cakes, bran, flour, brooms, salt, baskets and arrowroots. While most of the goods produced were consumed within the Nancowry Penal settlement, coconut oil was exported to meet the requirements of the Port Blair Penal Settlement as well (Annual Report 1875-76). The settlement established their own coconut plantation comprising a few thousand trees, the produce of which was mainly used for the extraction of coconut oil. Some quantity of nuts was also purchased from the Nicobarese. In the early years, in order to ensure a certain supply of coconuts from the Nicobarese to the settlement, a regulation had been introduced restricting trading vessels to western coasts alone (Annual Report 1873-74:49). However, in 1874, with most of the convict labour employed in the reclamation of swamps, the production of coconut oil fell and it was decided to concentrate production of coconut oil for local needs alone (Annual Report 1875-76).

Efforts at cultivating species both for food and trade were constantly practiced throughout the nineteen-year period of the settlement. Cultivation was only possible in the deep valleys and ravines or even better, jungle land. The infertility of the grassland was attributed to the existence of a thin layer of black mould suitable for grass alone. Below the thin layer of mould was Polycistina clay inhospitable for any other form of cultivation. To meet the food requirements of the settlement, Indian vegetables and fruits such as sugarcane, com, pineapples, yams, plantains, mangos, jackfruit, tamarind, and papayas were grown rather successfully on land reclaimed from the jungle. Rice, lentils and sesame were also grown for some years on reclaimed swamp land with some success. Beside this, experiments were made in cultivating American cotton, tobacco, coffee, and sunflowers. Some 20 acres were planted with American cotton between 1870 and 1873, but the intense dry months as well as the heavy rains destroyed the crop. An additional cause of problems was the ravages of the red beetle, that had apparently came along with the imported seed from America. The sunflowers fared equally badly. The experiment with tobacco turned out to be better than the cotton but the value of what was produced was insignificant. It was proved that coffee could be satisfactorily grown using proper treatment methods but its cultivation was not actually carried out thereafter. Trees valued for their timber such as mahogany, teak and eucalyptus were also grown. However, most of the timber extracted during this period, to meet local construction requirements as well as for sale, was from the forest and involved several thousand trees (Man 1903:191-192). Apart from the above mentioned flora, several faunal species from India were introduced as well, among them, deer, peacocks, crows, pigeons, bul-buls, and hill mainah (Man 1903:193).

The existence of a vast area of grassland on Kamorta island, unfit for any other purpose, led to the establishment of a cattle farm in the early years of the settlement. The objective was not only to ensure a sustained meat and dairy supply for the Nancowry settlement, but also to supplement the "outturn of draught and slaughter animals from the herds at the Andamans for the requirements of Port Blair, thereby eventually rendering that settlement independent of supplies of cattle from India" (Man 1903: 191). Animals pn the cattle farm included both cows and buffaloes, and a small number of sheep and goats. The project fared extremely well and met its objectives. At the time of the abandonment ofthe settlement in 1888, the farm comprised 1,033 cattle. During the period of the Penal Settlement, besides meeting local meat and dairy requirements, 227 cattle were transferred to Port Blair as draught and slaughter animals in the last three years, that is, between 1885 and 1888. The total value of dairy products (milk, yoghurt and butter) obtained from the cattle farm during these years was calculated to be Rs. 28,500 (Man 1903: 191). Grass for the cattle was abundant for most of the year but some also received a diet-supplement of oil cakes, the solid remains of the coconut meat after extracting the oil (Annual Report 1881-82:76). Grass became scarce during the dry months, i.e. from March to May, when the cattle were fed with grains that had been imported from the mainland (Annual Report 1877-78).

Another enterprise to which the settlement turned to was the processing of coconut fibre for export to Calcutta. It was envisioned that the project using convict labour would bring some economic remuneration to the settlement (Annual Report 1877-78). In only a year it was discovered that the money made, "after deducting the cost of the raw material, local carriage, and wear and tear of tools, barely sufficed to cover the charge of convict labour expended in working up the fibre" and the whole idea had to be abandoned (Annual Report 187879:40). However, following approval by the British Government, the manufacture of coconut oil was recommenced in 1880-81 on a larger scale to meet the consumption requirements of both Penal Settlements, as well as for export to Calcutta. The enterprise proved to be remarkably lucrative, bringing a profit to the settlement of Rs. 8,503 and Rs. 8,042 in 1880-81 and 1881-82 respectively. At the same time, expenditure was further curtailed by not having to import castor oil from Calcutta for use at Port Blair (Annual Reports 1880-81 and 1881-82). Despite the profits, the project was once again abandoned for two reasons. The first was an emerging conflict between the convicts and the Nicobarese, when the former were sent to the villages to collect coconuts. The second concerned the negative impact on local trade as a result of selling coconut oil on the open market. The interference in local trade conditions which the British government intended to foster was undesirable. Once again, coconut oil production was once again reduced to satisfying local needs (Annual Report 1881-82).

The British administration made several attempts to colonise and develop the Nicobars beyond the confines of the Penal Settlement by inviting foreign settlers, particularly the Chinese. In 1874, small plots around the settlement were leased out freely for a period of ten years to Chinese and Burmese labourers employed at the local establishment. Though the lease was on moderate terms, the cultivators did not take much interest in clearing the land and therefore, the scheme was abandoned after a few years (cf. Mathur 1968:288). In 1882, the British administration at Port Blair once again raised the issue of developiqg the islands and made liberal proposals to the pioneering Chinese colonists at Penang[12] (Mathur 1968:288, Annual Report 1884-85:83). In 1884, fifteen Chinese cultivators were brought from Penang for a term of two years, during which they were entitled to a daily ration of 24 ounces of rice and half a pound of salt fish each. In addition, they received the right to sell their produce on their own terms. At the end of two years, a free passage back home was offered if they wished to return, or licences on extremely liberal terms in case they decided to stay (Mathur 1968:289). However, the scheme failed once again due to illhealth and the lack of enthusiasm on the part of the Chinese for cultivating the land. Moreover, most of them were addicted to opium and, when their stocks ran out, could not be induced to work anymore. All except three returned in 1885, and those who had stayed followed suit the next year (Annual Report 188586:88 & Annual Report 1886-87:90). By now opinion about the Nicobars was not at all favourable among the Chinese at Penang and the British Government found it difficult to persuade other people to come to the islands. As a result, the idea of developing the islands with foreign settlers was abandoned after it had cost the government some Rs. 3,049 (Annual Report 1885-86:89).

12 Penang was one of the harbours of the Prince of Wales Island and was part of the British Straits Settlement. Each year, a large number of Chinese migrated to Penang to work as agriculturalists or as labourers. However, at this time, Penang experienced a shortage of Chinese immigrants owing to their preference for working on the prosperous tin-mining estates in Perak and other regions of the Malay peninsula. Similarly, the attractions offered by the vast and flourishing Dutch tobacco and spice plantations in Sumatra enticed away thousands of Chinese from Penang (Annual Report 1884-85:83).

|

|

Figure 7.1. Madras Infantry, Nancowry Islands (ca.

1900) |

Considerable efforts were made by the colonial administration to establish congenial relations with the Nicobarese. Trust of a kind was gradually building up as evident in the visit by some of the Nicobarese to the settlement for medical aid and barter trade (Annual Report 1873-74:44 and 1879-80:58). Upon several instances, the Nicobarese took an active interest in capturing escaped convicts and handing them over to the authorities. The British invariably rewarded these Nicobarese with customary presents for their co-operation (Annual Report 1874-75:48, Annual Report 1875-76:48). Whenever possible, visits were made to other islands as well to establish friendly relations with the Nicobarese (Annual Report 1875-76:48). In 1882, the Chief Commissioner, in a formal notification, laid down the policy (read strategy) for British officers to adopt towards the Nicobarese so as to ensure amiable relations with them and to ensure their full co-operation. It was decided to nominate a headman in every village near the harbour, who would be looked upon to keep the administration "acquainted with any unusual event which may occur within the limits of their respective charges" (Temple 1903:239). The Chief Commissioner further announced that:

The distribution of these certificates might be made the occasion of some little ceremony to show the Nicobarese that we are desirous of investing headmen with influence, and of treating them with consideration...The nominees, who may thus assemble to receive their certificates, might be entertained during their stay at the station at Government expense and suitable presents bestowed upon them before their departure to their homes... It is probable that the appointment of these headmen will not at first effect any material change in our relations with the Nicobarese, nor indeed would it be advisable to exact much from them in the first instance, but once appointed all intercourse with the villagers should be conducted through these headmen, whose influence through their connection with Government would, in course of time, be recognised by the villagers... (Temple 1903:239).

In early 1883, nine Nicobarese, selected from among those already exercising a certain degree of influence, such as captains or menluana (doctorpriest), were nominated as headmen in a ceremony at which certificates were awarded (Annual Report 1882-83:69). In the same year, three Nicobarese from Car Nicobar were sent to Calcutta so that their likenesses could be modelled for an International Exhibition. Later that year, four Nicobarese from Nancowry were sent to participate in the International Exhibition so that "they might both see and be seen at the Exhibition" (Annual Report 1883-84:84).

In 1884, the vessel I.M.S Nancowry was placed at the service of the Nancowry Penal Settlement. The vessel, now stationed permanently at Nancowry, facilitated communication with other islands as well. Until then, the British had remained familiar only with the Nicobarese around the settlement, but this development gave them the possibility to establish contacts and inform themselves about the inhabitants of the rest of the Nicobars, including the Shompen, the inland tribe of Great Nicobars (Man 1903:193-194). Consequently, the administration discovered a custom prevalent .among the inhabitants of Car Nicobar, which the British termed "devil-murder", that they were determined to stop (Man 1903: 193). According to this practice, "those individuals whose conduct is regarded as in any way suspicious either possess the Evil Eye, or, at any rate, have dealings with the powers of darkness, whereby they are able to exercise a malign influence over the health and fortunes of their neighbours" would be taken unawares, strangled and tom to death. The bodies of such people were usually taken to sea and sunk with stones in the belief that the risk of their spirits haunting the island is reduced (Man 1903: 193). Since the inhabitants of the Nicobar islands had been called upon to "submit themselves to Her Majesty's laws as administered by the Government of India" (Official Correspondence 1852-1869:318), the custom of "devil-murder" was judged to be clearly illegal. For the first time, the British administration took a firm step towards interfering in local customs that in their opinion were considered unlawful and to punish those found "guilty" of such "offences":

The cases first brought to our notice (in March 1884) all related to the preceding six or eight months, and the particulars furnished by our infonllants were amply verified by the admissions of the accused, who were in evident ignorance of the rigid views held by the civilised races regarding offences affecting life, and of the penalty attaching to the crime of murder... The nine men concerned in these several crimes were sentenced to long tenns of imprisonment at Port Blair by the Local Government. The punishments inflicted on this occasion, besides serving as a useful deterrent, contributed more than any previous act to instil a sense of, as well as a respect for, our authority throughout the group (Man 1903:194).

The British discovered that what the Nicobarese dreaded most were the spirits of those dying far from home (Man n.d:166). The "procedure adopted, therefore, was to bring the actual murderers over to Port Blair, in the Andaman Islands, and keep them there until they were thoroughly frightened by their own superstition that the most dangerous spirit was that of a man who died away from home" (Temple 1924:12). In the course of time, "devil-murder" was considerably reduced and eventually stopped. Thus, the British successfully controlled cases of "devil murder" by simply using the Nicobarese' own beliefs against them.

|

|

Figure 7.2. A group of Nicobarese at Malacca village, Nancowry Island (Courtesy Museum flir Volkerkunde, Vienna) |

For several years, providing education to the young Nicobarese was also discussed by the administration. Between 1882 to 1884, the parents of four Nicobarese boys at Nancowry were persuaded by the officer-in-charge of the settlement, Mr. A. de Roepstorff , to send them to his home for lessons in reading and writing. One of the boys "made considerable progress both in writing and speaking English" (Annual Report 1883-84:84). While the possibility of founding a school in the vicinity of the settlement was still remote, the inhabitants of Car Nicobar were showing considerable enthusiasm for sending their children to the school at Port Blair[13] to acquire knowledge of English and Hindustani. "The yearning is explained by the well-known fact that such status as their communistic customs permit one to enjoy over others is due in great measure to the extent of knowledge of foreign languages possessed by such individuals" (Annual Report 1883-84:85). Finally in 1887, sixteen Nicobarese boys were brought to Port Blair for education, of which only one was from Nancowry[14], and the rest from Car Nicobar. The boys received education at the Andamanese Home from the catechist Solomon[15] from Madras, in English and religion "of which they are entirely ignorant" (Annual Report 1887-88:72). The following year, the number increased to seventeen, and according to the report of 1888-89, "great progress [was] made by the lads and their willingness to remain at school" (Annual Report 1888-89:106). Already, deliberations were taking place to transfer the catechist Solomon to Car Nicobar with suitable arrangements for educating the Nicobarese on a much larger scale (Annual Report 1888-89:106).

13 The British, in order to control and pacify the Andamanese with whom they had several violent clashes, established a school cum orphanage in September 1869 at Ross Island to impart education to the Andamanese children (Mathur 1968 :97).

14 The boy from Nancowry was called Kanapi and is reported to have been remarkably intelligent (Annual Report 1887:88:72).

15 Solomon's original name was Vedappan Thambuswamy.

The Nancowry Penal Settlement lasted nineteen years, after which it had to be discontinued, while still keeping British sovereignty over these islands. The orders to terminate the settlement arrived in July 1888 from the colonial Government of India in expectation of continued expenditure without even the prospect of adequate returns. Further, the objective of suppressing piracy seemed to have been achieved and trade was running smoothly. During the nineteen years of the settlement, not a single case of piracy was reported and the survivors of seven wrecked vessels on the shores Nicobars had been treated kindly by the Nicobarese (Mathur 1968:292). In essence, "there remained neither inducement nor justification for maintaining an establishment any longer in such a remote and malarious locality" (Man 1903: 188). E.H. Man[16] writes with respect to piracy:

With our present knowledge of the Nicobarese and of some of those who have been in the habit of trading with them, there can be no doubt that the former must frequently have received considerable provocation from the latter (Man 1903:188).

16 Son of Col. Henry Man, and himself a British officer in the Andaman and Nicobars from 1869 to 1901.

By the end of the settlement at Nancowry, the infrastructure that had been created amounted to five barracks, four bungalows, seven small residential quarters, a commissariat store, a brick tank, two regular tanks, one magazine, twelve brick wells, metalled roads, drains (brick, surface, and sub-surface), sea walls, a 500 ft.-long jetty, and numerous outhouses, cattle and work sheds (Man 1903: 190). From dense jungles, the British had managed to set up a working establishment with reasonable housing, agriculture, animal husbandry, postal service, bakery, commissariat, a frequent communication with Port Blair, and a regulated system of law and order. However, by the end of 1888, the entire establishment was dismantled and transported to Port Blair, including the livestock. As a temporary measure, a Chinese interpreter who had been in government service at Nancowry, was left behind with the responsibility and "authority to register ships' arrival and departures, grant permits to trade and port clearances, and to hoist the British flag daily at the old station flag-staff" (Man 1903:188).

The colonial period (1888-1947)

The British retained control over the Nicobar Islands even after the closure of the Nancowry Penal Settlement. Regular visits were made to the islands, in particular to Car Nicobar and Nancowry, but at times the vessel went as far south as Great Nicobar. Government vessels that made their usual tours to the islands were like mobile administrative units. The officer-in-charge of the Nicobars was the overall administrative officer on board, but at times he was accompanied by senior officers from Port Blair as well. The vessel visiting the Nicobars had several functions. Besides providing passage to people both within and outside the government for specific purposes, the vessel served as a mail carrier to the non-native residents on the islands, including traders. The practice of renewing or handing out new certificates, western suits, and other presents to headmen continued. The officer-in-charge would inform himself of events that had passed in the islands since the last visit, collect the revenue generated by granting trading licenses and residence permits and impose fines on trading vessels without a valid license or those trading in arms and liquor.[17] In addition, ethnological and natural science investigations of the islands were carried out by visiting scientists and administrative officers posted at Port Blair (see, for example, Annual Reports of 1896-97 and 1898-99, Man 1903:193-196). Among the visiting officer's duties, the most important was the maintenance of law and order. Upon arrival, a temporary court would be set up where all sorts of cases would be brought forward for hearing. The cases were of two common types. The first were trade-related cases emerging from constant disputes between the traders and the Nicobarese. These cases were invariably numerous each time the court was held, as revealed from the annual reports of this period. The second were classified as criminal cases usually occurring when these trade quarrels had resulted in murders. Cases of "devil-murders" fell into the latter category and were dealt with directly at Port Blair, where the accused and witnesses were brought for the hearing (Temple 1903:201). Punishments included cancellation of trading licenses in case of traders, fines, imprisonment at Port Blair, or a combination of these. The Nicobarese feared their detention at Port Blair because of their fear of dying far from home, which usually served as a deterrent from engaging in any form of murder. Annual reports of this period document most of these cases that were brought to court and the punishments handed down. In a majority of these situations, we find that the source of conflict was the provocation by the traders of the Nicobarese caused by their high-handed behaviour.

17 The prohibition to import spirituous liquors, arms and ammunition to the Nicobars without a license was enforced in November 1880 (Annual Report 1880-81 :55, Man 1903: 183). The addiction of the Nicobarese to alcohol was constantly noted by the administration, and especially how this obsession was exploited by the traders who then imported cheap alcohol (arrack) to sell to the Nicobarese at high prices. Further, once the N icobarese were drunk, the former could make the latter buy anything at the cost specified by the trader (Roepstortf 1881, cited in Temple 1903:173). A similar strategy is being used by present-day traders.

At first the only permanent representation of the administration was an agent at Nancowry whose task was to "assist the chiefs in keeping order, to collect fees for licenses to trade in the islands and to give port clearances, to report all occurrences, to prevent the smuggling of liquor and guns, and to settle petty disputes among the people themselves or between the people and the traders as amicably as may be" (Temple 1903:201). Nearly ten years later, in 1897, Solomon was given the dual role of a catechist and government agent at Car Nicobar (Annual Report 1897-1898:169). Although such an appointment had been contemplated for several years, the immediate cause was the death of six Car Nicobarese boys receiving education at Port Blair. In early 1895, the boys had surreptitiously planned a voyage to Car Nicobar from Port Blair by canoe and were consequently lost at sea. The loss of these boys induced the British administration to consider a mission school at Car Nicobar itself (Annual Report 1894-95:119-120). Besides, there was a growing interest in Car Nicobar on the part of the British administration. There were several reasons for this: nearly half the archipelago's population was concentrated on Car Nicobar; half of the coconut production was on Car Nicobar and there was much trade activity; the Car Nicobarese were open towards new forms of learning and interacting with foreigners; the fact that the island was the nearest from Port Blair was perhaps an additional advantage. The potential of Car Nicobar was repeatedly acknowledged by many officers:

There is room for grand work in the Car Nicobar, but it will, as I have before remarked, require time, patience, and perseverance. We must not expect any very great immediate results. The process of education in Christianity and civilization must necessarily be slow. There is much to learn and much to unlearn; but, I believe, there is a great future in store for it (Annual Report 1897-98:169).

In 1896, negotiations were made for a segment of land at Mus village on Car Nicobar, where the mission school (including the agent's residence) could be established.[18] Within a year, the land was cleared and with materials and convict labour brought from Port Blair, the mission building was ready for occupation in 1897.[19] The first agent for Car Nicobar was Solomon, whose task was similar to that of his counterpart in Nancowry but who had an additional charge to run a mission school and to take meteorological readings regularly. The mission school was part of the efforts of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts (SPG) with regional headquarters at Rangoon.[20] In a short period of time, Solomon came to exert much influence over the Car Nicobarese:

... the Car Nicobarese soon became reconciled to the establishment of the new Mission building at Mus village: indeed it is probable that they would now regret to see them removed. This is in great measure due to the tact and intelligence displayed by the Catechist Solomon, who has lost no opportunity of exerting his influence in the settlement of disputes amongst the islanders or between them and the ship-traders: His influence and importance have doubtless been considerably enhanced in their eyes by the fact of his being provided with what they must regard as a palatial wooden house as well as other buildings for his school and meteorological instruments (Annual Report 1897-98:175).

18 The barter price paid in exchange for the land to the owner Offandi was "five bags of rice, six suits of black broad-cloth, one piece of red cloth, twenty packets of China tobacco, and one or two other small articles" (Annual Report 1895-96:136).

19 The practice of using convict labour for repairing or constructing government buildings or structures was invariably continued. The convicts were brought in such regular sailings and were taken back on the return of the vessel. Never were the convicts left for a longer period under the supervision of the agent alone (Annual Reports 1895-96 onwards).

20 From the beginning of English colonisation, a need for spiritual guidance for colonists and missionary work among natives was perceived by church leaders, but performance fell short of the hazily perceived goals. In 1675, an official inquiry was undertaken by the Church of England, but it was not until 1698 that the Society for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge (SPCK) was formed, and even then, its scope was limited. In 170 I, a special committee was appointed by the Lower House of the Convocation of Ihe Province of Canterbury to inquire into "ways and means for Promoting Christian Religion in our Foreign Plantations". This committee sent a petition to King William III, who returned a charter founding the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts (SPG) in 1701.

The appointment of a government agent at Car Nicobar, the establishment of the first mission school, its large population and high coconut productivity coupled with the accommodative nature of its inhabitants went a long way towards enhancing the prestige of Car Nicobar throughout the archipelago. In the space of just ten years, Car Nicobar was looked upon as the administrative headquarters of the Nicobar Islands. Without warning, in 1908, the post of the government agent at Nancowry was reduced to that of an assistant agent and was brought under that of the agent of Car Nicobar (Annual Report 1908-09:45). In 1918, a European was appointed as the government agent on Car Nicobar (Annual Report 1918-19:36). In 1921, the post of the agent was raised to that of "Assistant Commissioner", the appointment to which was invariably a British officer[21]. In the same year, the post of the assistant agent at Nancowry was raised to that of a Tahsildar[22] . In 1918, for the first time, a British officer was permanently posted at Car Nicobar and was made responsible for the supervision of the entire archipelago (Annual Report 1921-22:41). The importance of Car Nicobar as the administrative headquarters for the Nicobars undoubtedly enhanced its prestige which continued to grow in subsequent decades.

21 The first British officer to hold the post of agent in 1918 and later that of Assistant Commissioner in 1921 was Mr. E. Hart who continued until till his death in 1928. From administrative reports we find that Mr. Hart and his wife had become extremely popular with the Nicobarese for their efforts in promoting education and other welfare programmes on Car Nicobar. His death was mourned by all. For a year, John Richardson (a Nicobari and a long-time student of Solomon) was given the position of Assistant Commissioner until, in 1929, the British officer Mr. R. Scott assumed office (Annual Report 1928-29:64).

22 A Tahsildar is a revenue officer below the Assistant Commissioner, a post stil1 existing throughout India at the lower administrative level.

The British maintained regular contact with the Nicobarese via their frequent visits to the islands. Certificates to headmen were renewed every few years, and presents were given out at every visit. On special occasions, the Chief Commissioner himself visited the islands to "read a Proclamation, present new suits, hats, flags, etc. and to provide a 'King's dinner' for all" (Annual Report 1902-03:46). Presents included the distribution of several hunqred fruit trees from the Indian mainland, including mango, orange, tamarind, and bae! to the Chiefs (Annual Report 1895-96: 137). The policy of the administration towards the Nicobarese, however, was coherent, constantly emphasizing that "while the Government is willing to treat them with great leniency, it is nevertheless determined to put down murder, and to apprehend murderers" (Annual Report 1894-95: 119). In this sense, we find that the British had a dual approach to keeping the Nicobarese under control: one employing positive feedback (e.g. rewards, social prestige) and the other threatening negative feedback (e.g. detention at Port Blair).

The school progressed slowly under Solomon. In 1899, he reported:

As these children are only beginners, I am unable to give just any account about their educational progress: some of them have finished the I st Royal Primer and could repeat Prayers. They could also stitch their own Jangyas [shorts], wash their own clothes and cook meals. I am also giving them some working exercise in the garden (Annual Report 1898-99: 178).

The mission was intermittently visited by the chaplain from Port Blair to inspect the school and supervise progress. His visits also became an occasion to baptise willing Nicobarese (Annual Reports 1901-02:46 and 1902-03:47). In 1903, while the chaplain held a prayer service on Car Nicobar, it was noted:

The manner in which the twelve boys of the Mission and some adult men and women who had been trained in the Mission joined in the service was most striking, and they recited the Confession, Lord's prayer, Creed, Magnificat and responses correctly and reverently. Twelve adult Nicobarese were baptised the next morning by the Chaplain (Annual Report 1902-03:47).

Solomon was gradually getting old and could no longer fulfil his duties actively by himself. Consequently, in 1904, he gave up his position as government agent and concentrated on the mission school instead (Annual Report 1904-05:42). To assist him, in 1905, he was provided with an assistant catechist at the mission school (Annual Report 1905-06:48) and the following year the new government agent for Car Nicobar arrived to take charge (Annual Report 1905-06:49). Henceforth, the dual post of catechist and government agent was split. In November 1909, after a service of sixteen years on the Nicobars, Solomon retired to return home. However, on his way home to Madras, he died at Rangoon soon after. His work was taken over by another catechist by the name of John (Annual Report 1909-10:46).

In 1915, a new post of "Deputy Superintendent" at Port Blair was created exclusively for the administration of the Nicobars (Annual Report 1915-16:39). The same year, a European missionary[23] was appointed to the charge of the S.P.G. mission at Car Nicobar which marked "a distinct step forward in' the civilization of the islands" (Annual report 1914-15:41). In the same year, the local British administration announced the building of a new school building, a separate boarding school for girls and boys, and housing quarters for the teaching staff (Ibid.), the first two saw completion the following year (Annual Report 1915-16:40). In the absence of a European missionary due to leave, the mission school remained under the charge of a Nicobarese teacher (Annual Reports 1916-17:36 and 1920-21:39). The first Nicobari teacher was John Richardson, a student of Solomon, who later became significantly influential and an important driving force of change among the Nicobarese. Owing to the popularity of education, two Government schools were opened on Car Nicobar, one at Lapati (with 36 students), and the other at Malacca (Annual Report 2223:38). By 1930, Car Nicobar boasted of five schools, including one mission school, with an average total strength of more than 100 students, including some girls. In all of these, Nicobarese language was taught, while two schools taught in English as well (Annual Report 1930-32). Already by 1927, six boys and a girl were receiving higher education at Rangoon (Annual Report 1927-28:53). The schools were now no longer under the S.P.G. mission but were taken over by the Bishop of Rangoon and were supervised through the Chaplain in Port Blair and in turn by the Car Nicobar mission. The work was supported jointly by government grants, collections in the church and the Central Diocesan funds (Annual Report 1928-29:64). The day-to-day educational activities was carried out by Richardson assisted by several teachers (Annual Report 1927-28:53). The popularity of the schools can be gauged by the fact that the two boys from Nancowry and Chowra were receiving education at Car Nicobar. The Assistant Commissioner at Car Nicobar was significantly engaged in the progress of education on Car Nicobar and in 1937 the supervision of all schools became his responsibility under the Rangoon mission with the local British administration paying an annual subsidy (Annual Reports 1936-37:21 and 1937-38:25).

23 The first European missionary to be appointed to the mission school at Car Nicobar was Reverend George Whitehead who spent several years on the island and later published a book, In the Nicobar Islands (1924).

The period beginning from 1915 saw considerable progress in the area of health as well. However, as noted earlier, the import of alcohol by traders was strictly prohibited under law already since 1880. Furthermore, constant efforts were made to reduce the consumption of tari (toddy) among the Nicobarese. As an alternate to toddy, the administration had tried to "induce a taste for tea among the natives and thereby discourage their excessive use of tari and fondness for ardent spirits" (Annual Report 1899-00: 159). Packets of Port Blair tea with teapots were distributed free of cost to influential people of Car Nicobar, Nancowry and Kondul along with instructions on how to make tea (Ibid.).It further came to the notice of the administration that new. illnesses such as influenza and measles were being introduced on the islands by visiting traders. To regulate the spread of contagious diseases, the administration, in 1915, made it mandatory for every trader to undergo a medical examination before landing at Car Nicobar (Annual Report 1914-15:41). At the same time, the construction of a hospital at Car Nicobar was also announced that was completed the following year. Prior to this, Nicobarese needing medical attention were brought to the hospital at Port Blair if they were willing (Annual Report 1899-00: 157). However, owing to the First World War, the hospital did not start until 1921 (Annual Report 1921-22:42). In the meantime, John Richardson received basic training in healthcare at Port Blair so that he could build the much-needed health service on Car Nicobar (Annual Report 191920:40). Unfortunately, in 1920, members of the church mission while on their holiday to Burma picked up the influenza epidemic and brought it over to Car Nicobar. Consequently, about 600 people, that is 10% of the population of the island, died (Annual Report 1920-21 :39). The following year, a sub-assistant surgeon was posted at the hospital on Car Nicobar (Annual Report 1922-23:38).

The period that followed, however, was far from healthy. In 1924, a smallpox epidemic took a toll of 32 people on Car Nicobar. As a result, the hospital staff vaccinated 1,700 Nicobarese against this disease and were able to control it by 1925 (Annual Report 1924-25:42). In 1926, smallpox and influenza broke out in Nancowry and adjacent islands though not with the same intensity as had been on Car Nicobar (Annual Report 1926-27:47). The following year again, influenza killed nearly 35 people on Car Nicobar, Chowra, Teressa and Nancowry together (Annual Report 1927-28:53). Between 1930 and 1932, there were several cases of dysentery, chest complaints and yaws (a venereal disease) that was previously prevalent only on less-frequented islands. With its spread to Car Nicobar, the number of cases spread rapidly over the years (Annual Report 1930-32: 11). It was discovered that the disease reacted positively to treatment if inoculations were arranged. The major difficulty the administration faced was to make the sole doctor available to all the islands to inoculate the infected. In March 1933, the Chief Commissioner, Bonington, himself visited the Nicobars with a sub-assistant surgeon who inoculated people at each island they touched. At the end of this trip, it was decided to post the sub-assistant surgeon at Nancowry where he would have a dual position of a Tahsildar and a local medical officer (Annual Report 1932-33: 1 0). The experiment of combining a medical officer with that of an administrative officer turned out to be good, except that, owing to the lack of a vessel, his services were restricted to the villages around Nancowry alone (Annual Report 1934-35: 16). In 1935, the dispensary at Nancowry was equipped with six beds and its status was raised to that of a Government Hospital (Annual Report 1935-36: 19). The hospital at Car Nicobar was also expanded to include an extra ward and two small rooms (Annual Report 1936-37:21). Constant examinations were made for yaws disease and in 1937 and 1938, more than 8,000 and 7,000 people had received treatment in the hospital at Car Nicobar respectively, several of which were for Yaws and other venereal diseases (Annual Report 1937-38:25 and 1938-39:28). In the later months of 1938, measles appeared in an epidemic form on Car Nicobar and Chowra complicated by bronchial pneumonia and resulted in high mortality among infants and the young. Several people also came from Chowra to Car Nicobar for treatment (Annual Report 1938-39:28). In 1939, the number of patients who had received treatment at Car Nicobar exceeded 9,000 but the number of Yaws cases were only slightly on the decline. The following year, influenza spread to most of the islands and mortality was high (Annual Report 1939-40:22).[24]

24 We do not know anything about the period immediately after 1940 since there exists no known documentation covering the Second World War when the Japanese occupied the islands from 1942 to 1945. See Japanese Nicobar.

At the time the islands became part of independent India, a fairly effective and unprecedented system of administration and communication had been established. Car Nicobar had a coast-to-coast circular road already by 1915. A wireless communication system between Port Blair and Car Nicobar was operational from 1939. There was a regular postal service connecting the islands with the outside world, although the frequency in the exchange of letters was only about three to four times a year. Car Nicobar was developed as the archipelago's headquarters with an infrastructure that supported several government officials, teachers and medical staff. Nancowry was second in prominence to Car Nicobar. During the 70 years of British sovereignty over these islands, a significant amount of data and information on the Nicobars and its inhabitants was compiled. Regular census operations were carried out every ten years, the first being in 1901. However, a first unofficial survey of the population and distribution patterns in the Nicobars had already been carried out in 1883 by an enterprising British officer, Mr. A. de Roepstorff. Results from the 1883 survey were found to be quite comparable with that of the official 1901 figures (see Table 7.1).

Table 7-1. Population of the Nicobar islands 1883-1941.

The trading world of the Nicobars 1869-1947

The British period, as we have seen, was far more dynamic than the preceding Danish one. The British administration had much more success in establishing a system of control and enforcing regulations throughout the islands. One can say that the British actually governed these islands, and in this sense, for the first time the Nicobars were incorporated into a system of statehood. The occupation of the Nicobars had a direct connection with trade. The occasional plundering of passing vessels had made trade with these islands rather insecure. As most of the vessels that had been assaulted were British, the matter could not be overlooked. It became a major concern for the British to put a stop to these massacres and make the region safe for trade. Immediately after the occupation of the Nicobars, the British sought ways of regulating activities in the islands, trade being one of the priorities in this regard. At the time the British established their administration over these islands, it was customary for vessels sailing to Rangoon from the Malacca Straits to visit the Nicobars for a cargo of coconuts which the traders "bartered at most advantageous rates for piece-goods and rum" (Official Correspondence 1852-1869:275, 301). However, prior to the British occupation, "piracy" in the central Nicobars had reduced the number of visiting vessels considerably. Trade picked up once the British established a Penal Settlement at Nancowry. Close surveillance was kept on the trading activities in the region. In only a short time, it was discovered that most of the cases of violence or so-called piracy were the result of provocation on the part of the traders (Man 1903: 188, Annual Reports 1872 - 1940). Stringent laws were established to ensure a certain level of control over the traders, "some of whom have habitually acted in an over-bearing manner towards the Nicobarese, as if imagining themselves to be well-nigh beyond the reach of law" (Annual Report 1883-84:82). Already in the early years following the British possession of the islands, it was made mandatory for traders to acquire a trading permit on payment thereby permitting them to trade in the islands.[25] This permit could be bought either at Nancowry (and later at Car Nicobar as well) or at Port Blair and had to be renewed annually. Every vessel, before its departure from the islands, was expected to obtain a port clearance from the local officer or agent and to declare the quantity of goods being exported. A register was maintained to ensure control, and to keep a record of the traders and their activities in the islands. However, it was not physically possible to control and monitor the trade of the entire archipelago. At the time the British had their Penal Settlement at Nancowry, monitoring activities were concentrated mainly on the central group with occasional visits to other islands. From 1889, mechanisms of control operated via the agents at Car Nicobar and Nancowry with five to six visits each year by officers of the British administration stationed at Port Blair. During these visits, the administration invariably fined those vessels that were caught trading without a permit or were engaged in any form of illicit trade. It was the objective of the British administration to foster trade in the islands, yet keep control over it. The success of their policy became evident already during the period of their settlement at Nancowry, since the number of vessels visiting the harbour increased constantly. E.H. Man reports that at the beginning of the settlement:

trade was confined to probably not more than 15 to 20 vessels, representing an aggregate of about 12 lakhs [1.2 million] of nuts, nearly of which was procured at Car Nicobar, the export trade for several years past [that is, 1880s] has been carried on by from 40 to 50 vessels, and the quantity of nuts shipped has ranged between 35 and 45 lakhs [3.5 to 4.5 million] (Man 1903:192).

25 The regulations for obtaining trading licenses were made mandatory at least by 1883, but the probability that they existed earlier cannot be ruled out (Annual Report 1883-84:82).

Even after the removal of the Nancowry Penal Settlement in 1888, the number of vessels visiting the islands remained more or less constant (see Figure 7.4). At the time of British occupation, most of the vessels that visited the Nicobars were British, coming for coconuts. Thereafter, however, the British were ousted from this trade within a short time and their place was taken by smaller vessels owned by Indian and Burmese merchants (Whitehead 1924:73).

Figure 7.5 shows an aggregated export of coconuts and copra from Car Nicobar, Nancowry, Kamorta and Trinket between 1875 to 1940. We find that trade was never constant but fluctuated every few years. The vicissitudes of demand and price for coconuts in Moulmein and Rangoon had a direct repercussion on the trade with the Nicobars (Annual Reports 1872-1940). During the First World War, it was found to be more profitable for vessels to devote their tonnage to war materials than coconuts. During this period, there was a decline in trade with the Nicobars (Annual Report 1917-18:36). However, after the war, we find a constant decrease in the number of coconuts exported. This decline is due to the fact that export in copra was increasingly becoming more important than the export in coconuts (see Figure 7.5).

|

|

Fig. 7.4. |

|

|

Fig 7.5. |

In 1882, for the first time, the Nicobar Trading Company Limited based at Penang applied and obtained permission to reside and trade at Nancowry. One of the necessities for traders to take up residence on the islands was for copra production. In the 1860s, Theodore Weber, the manager of the Samoa branch of the German company Godeffray und Sohn pioneered a major invention that revolutionised commercial planting in the tropics. This was the discovery that coconut meat scooped from the shell and dried (called copra) could be exported instead of coconut oil. On arrival, the oil could be extracted in Europe for use in many industrial products, while the residue served as valuable cattle feed. Weber's innovation laid the foundations for the copra industry (Meleisea 1980: 1-3). It was not long before copra production was introduced in the Nicobars as well.[26] Traders bartered the coconuts from the Nicobarese and sundried them into copra that was eventually exported. The tropical climate of the Nicobars allowed copra production only during the dry period of the northeast winds when sunshine was abundant. At first, copra comprised only a small part of the exported cargo in relation to coconuts. Over time, this pattern changed and most of the coconuts bartered in the Nicobars began to be converted to copra. Copra production required traders to take up residence on the islands for some part of the year. Furthermore, the Nicobars were gaining prominence as an important source for coconuts which induced the traders to establish semipermanent bases on the islands. Residing on the islands had its own advantages: a good rapport with the Nicobarese and favourable negotiating conditions, in which the traders invariably had the upper hand.

26 The first mentions of copra production in the Nicobars is found in the Annual Report of 1883-84, though presumably it has must have started much earlier.

With the Nicobar Trading Company obtaining a license to reside and trade in the Settlement, the administration, in 1882, laid down regulations.[27] for all those traders who wished to follow suit (Annual Report 1882-83:68). Under the new regulations, traders could obtain a permit to reside within the Nancowry Penal Settlement area. The administration had built some huts where these free traders could live. Permission, however, for residing on other islands of the archipelago was limited to the dry period alone. Traders visiting the islands on a short-term basis for the purpose of bartering coconuts and converting them into copra had to obtain the usual trade license upon their arrival. Vessels arriving in the Nicobars via the Andamans had the possibility of purchasing their trading licenses at Port Blair (Annual Report 1883-84:82). The Nicobarese of Car Nicobar were for some years opposed to traders establishing their shops and houses in the villages. Traders had been customarily restricted to the Elpanam (community space at the beach) where they could live.[28] and trade, and at the end of the bargain, were expected to leave (Whitehead 1924:76). However, this changed in the late 1890s with the arrival of Solomon as catechist and agent who, through his influence over the Nicobarese, gained allowance for the traders to establish shops and houses in the villages and live there for as long as they desired (Malhotra 1998:60).

27 These rules were laid in accordance with Part V of the Andaman and Nlcobar Regulation 1976 (Annual Report 1882-83:68).

28 The trader's huts were rectangular in shape as opposed to the round beehive huts of the Nicobarese (Whitehead 1924:76).

|

|

Table 7.2. |