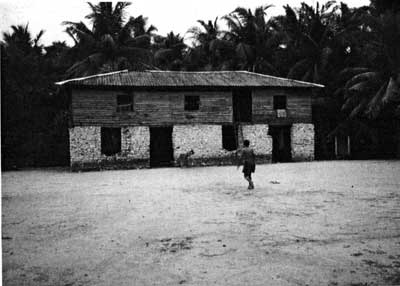

Figure 8.1. An example of new housing style on Car Nicobar: a traditional house raised above a concrete hall

The Nicobar Islands

The Nicobars in the Indian Union

by Dr. Simron Jit Singh

|

Table of Contents

A world system perspective of the Nicobar islands 1756-2003

Afterword 2005 by George Weber |

|

The following texts have been selected by Gorge Weber from a much more extensive treatise on the subject by Dr. Singh, originally published as Chapter 8 (The Welfare Approach, pp. 243-264), Chapter 9 (Trade, Actors and Interest Groups, pp. 227-241) and Chapter 10 (A World System Perspective of th Nicobar Islands 1756-2003, pp. 293-310) in Dr. Singh's In the Sea of Influence - a world system perspective of the Nicobar Islands, Lund Studies in Human Ecology 6, Lund University, Sweden, 2003, ISBN 91-628-5854-8, ISSN 1403-5022. Copyright ©2003 Simron Jit Singh Footnotes are marked in the text with square brackets [ ] and can be found at the end of the following paragraph. They are numbered differently from the original and much longer work. For references mentioned in the text consult the printed book. |

During the negotiations for a free India, it was apparent that the British did not want to part with these islands, and in particular the Nicobars, primarily for their strategic military location. The Secretary of State, writing to the Cabinet in May 1947, asks:

The Chiefs of Staff have raised the question whether in the course of the transfer of power to India, it cannot be arranged for the Andamans to come under British Government because of their strategic importance as a potential naval and air base (cited in Tamta 1991:69).

A year before, in October 1946, Sir S.O. Monteath of the India Office wrote to Major General Sir L. Holls to even consider leasing the islands from the Indian Government:

The matter of the Andaman and Nicobar islands presents considerable difficulties because these islands have long been recognised as Indian Territory. It is unlikely that India will be willing to forego the sovereignty of these islands, and I should be glad to know whether the Chiefs of Staff consider that essential requirements could be obtained under an arrangement by which we were able to have lease basis in these islands for a long period of years (cited in Tamta 1991:68).

The Viceroy of British India, Lord Mountbatten, knew rather well that the Indian people had a sentimental attachment to these islands because of the Penal Settlement and would never agree to part with them. The minutes of a Cabinet meeting records:

The secretary of State for India said that, in the opinion of the Viceroy there could be no question of raising this controversial subject at the present delicate stage of our political negotiations. It is a matter on which Indians felt deeply. Any attempt by His Majesty's Government to separate the islands from India would probably provoke violent opposition from all parts of India (cited in Tamta 1991:69).

The British, however, tried their best to keep the islands to the extent that in the draft bill prepared for the transfer of power, a provision to secede the islands from India was inserted. When Mountbatten saw the draft bill he was concerned about his position while facing the Indian leaders. Such was his dilemma that it was recorded in the minutes of a staff meeting:

His excellency said that he had been amazed to find in the Draft Bill provision that the Andaman and Nicobar Islands should cease to be part of India after 15 August. But it was not for him to attempt to disguise the intention and desires of His Majesty's Government in this respect. He considered that it would be better to allow this paragraph to be circulated to the leaders to come out in the open and then try to negotiate an agreement with them... if the leaders wished to contest this, some alternative means of satisfying His Majesty's Government would have to be found. His excellency said that so far as he knew, all His Majesty's Government really wanted were the harbours and airfields on the islands. It would have to be a matter of negotiation...Was there incidentally, any chance of splitting the difference leaving Andaman Islands in India and taking over Nancowry and the Nicobars? (cited in Tamta 1991:70).

When Mountbatten hesitantly approached the matter with Jawarhar Lal Nehru, the Indian leader to later become the first Prime Minister of India, the question of the Andaman or the Nicobar Islands seceding from India was refused outright (Tamta 1991 :70). The British, however, did not lose hope. Major Boomguard, the Deputy Commissioner of the Nicobars who succeeded Mr. Scott, went so far as to induce the Nicobarese to apply and seek for independence. He even prepared an application for independence and had it signed by several Nicobarese, including John Richardson, and forwarded it to the higher authorities in Delhi. The matter was soon in the newspapers and following an uproar, Major Boomguard was transferred from the Nicobars.[1] The islands thus continued to be part of independent India,[2] but the British with their remarkable negotiation skills managed to retain the use of the airfield of Car Nicobar for the Royal Air Force until 1956 (Tamta 1991:70).

1 The source of this information is an un-authored and unpublished note written by a member of the Jadwet family associated with the firm Akoojee Jadwet & Company that had been trading with the Nicobars since at least the turn of the last century. At the end of the war, the British appointed them as the Government's licensed traders to supply daily commodities to the Nicobarese.

2 India became independent from the British rule on 15 August 1947.

The foundation for future development in the Nicobars was already provided by the British during their seventy-eight years of control. In this period, the English achieved much success in setting up a regular system of administration over the Nicobars which the Danes prior to them had repeatedly failed to establish. By the time India took over the islands in 1947, a basic network of administering the islands had been set up. The authority of the administration came to be acknowledged by the Nicobarese as well. By now, the Nicobarese were somehow acquainted with the idea of being governed by a state and having to abide by their written laws. Apparently, the Nicobarese had found it impossible to resist a power superior to their own, and had gradually come. to integrate an external system of the civic-state within their own traditional one.

Under independent India as well, the islands remained under the direct control of the central Government at Delhi, at first through the already existing office of the Chief Commissioner at Port Blair, and then from 1982, through the Lieutenant Governor. Port Blair continued to act as the archipelago's headquarters. With the Constitution of India coming into force in January 1950, the islands were awarded the status of a "Part D" state (Das and Rath 1991: 102).[3] In the same year, a certain category of tribes, "Schedule Tribes", was constituted with special rights conferred upon them by the President of India. The Constitution of India provides no definition as to which tribe are entitled to belong to such a category.[4] The President of India alone is vested with the authority to declare any tribal community a "Schedule Tribe" through an initial public notification (Tribal Affairs 2002). Consequently, 245 tribal groups with a total population of nearly eighteen million was listed by the President as "Schedule Tribes". Among them were also the Nicobarese. According to the census of 1951, the total population of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands was recorded to be 30,971, a third (12,009) of which lived in the Nicobars (Census of India 1951). Almost all of the non-aboriginal population in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands (i.e. about 17,000) consisted of former convicts and their descendants. During the period of British rule, convicts who had completed their jail terms were compelled to remain on the islands as "free residents" (Temple 1903:354). Under independent India, most of these "free residents" voluntarily remained behind and saw no point in returning to their former homes after so many years to re-establish broken ties or renew weak ones.

3 Under Article 243 (now repealed), it was laid down that the territories included in Part 'D' of the First Schedule (only the Andaman and Nicobar Islands in Part 'D') were to be administered by the President of India, acting through a Chief Commissioner or other authority appointed by him. The President had powers to make regulations for the peaceful governance of these territories and such regulations had the force and effect of an Act of Parliament. Furthermore, the regulation could repeal or amend any law made by Parliament (Das and Rath 1991:102).

4 The criteria used in defining and ultimately registering a group as a "Tribe", resp. Caste, were normally arbitrarily fixed, changed and used, or else the groups fitted the criteria only partly or to a very limited extent. At the times of the Census reports, the following criteria were applied to "Tribes": geographical isolation, animist religious beliefs, own language, simple technology, little division of labour, low-level political organisation, egalitarian society, indigenous status. The term "Scheduled Tribe", is thus a technical term and in the context of modern India, above all a political administrative category .

In 1952, the Andaman and the Nicobar Islands came under the direct control of the office of the President of India. Representing the entire population of the Andaman and Nicobar islands to the Indian Parliament was the Nicobari leader John Richardson. Already ordained as a bishop in Burma in 1950, John Richardson was nominated in 1952 by the President of India as the first Member of Parliament (to the Lok Sabha or the Upper House) to represent the islands (Das and Rath 1991:102).[5] With the nomination of Richardson as MP, Car Nicobar, his native island, was elevated to an even higher status in all political and administrative senses. A host of VIPs, including the Presidents of India,

5 Under the Representation of Peoples Act, 1951, the islands were allotted one seat in the Lok Sabha to be filled by a person nominated by the President. Subsequently, under the Union Territories Direct Election to the House of People Act, 1965, this provision was changed to that of direct election (Das and Rath 1991:102).

Prime Ministers, and several Cabinet Ministers began to visit Car Nicobar, the island that in many ways represented the remotest of the Indian territories. As the island with the highest density ofNicobarese population, along with political representation at the centre through John Richardson, Car Nicobar became the axis of the archipelago.

In 1956, the re-organisation of Indian states took place, following which the "Part D" states were re-named as "Union Territories" (UT) (Das and Rath 1991:102). The Union Territory of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, as they henceforth came to be called, nonetheless continued to be administered by the Chief Commissioner, who was advised in all legislative and policy matters by an advisory committee nominated by the central government (Das and Rath 1991:108). One of the members of this advisory committee was an educated Nicobari selected from among the village headmen (Justin 1990:97). Several departments for the administration and development of the islands were set up at Port Blair and senior administrative officers from mainland India were given charge of these departments. The Chief Commissioner was assisted by a Deputy Commissioner at Port Blair, who was responsible for the day-to-day general affairs of the administration.

In order to integrate the Nicobars into the development process, the administrative structure at Car Nicobar was further developed. The Assistant Commissioner, the highest authority in the Nicobars, came to be superseded by an Additional Deputy Commissioner. Simultaneously, the post of Assistant Commissioner was created at Nancowry who superseded the Tahsildar. Senior officers from several welfare and administrative departments were also positioned at Car Nicobar. However, besides carrying out development and welfare programmes, the local administration were not allowed to interfere in tribal affairs unless serious law and order issues arose. The Nicobarese continued to own their lands legally, and to manage their own day-to-day affairs through their traditional tribal system of leadership and elders that was recognised in lieu of the "Village Panchayats" (village local self-governance elected bodies) on the Indian mainland. With a view to providing special protection for the "interests of socially and economically backward aboriginal tribes in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands", the Andaman and Nicobar Protection of Aboriginal Tribes Regulation was enforced in July 1956. The following year, through a notification issued on 2 April 1957, several parts of the Andamans inhabited by the four aboriginal so-called "negrito" populations and most of the Nicobar Islands were declared out of bounds. Entry into these areas was highly regulated and required a special pass which could be issued by the Deputy Commissioner or his nominated representative (ANPATR 1956).

In March 1961, the advisory committee of the Chief Commissioner was reconstituted and placed under the control of the Indian Home Ministry. The new committee comprised, besides five non-official members nominated by the central Indian Government, the Chief Commissioner, the local Member of Parliament and a senior representative of the Port Blair Municipal Committee. One of the non-official members nominated to the Home Minister's advisory committee was a Nicobari.[6] The Member of Parliament from these islands continued to be nominated by the President of India to three consecutive national Parliaments. It was only during the fourth general election of 1967 that the local population were allowed to elect their own candidate to the Indian Parliament (Das and Rath 1991: 127).[7]

6 The first person to become a member of the Home Minister's advisory committee was Rani Lachmi. After her death in 1989, her granddaughter, Ayesha Majid, was nominated to the same position, which she continues to hold today (Yusuf 2003).

7 Following John Richardson. the other two nominated MPs were Laxman Singh and Lala Niranjan Lal in 1957 and 1962, respectively, both belonging to the Indian National Congress (Das and Rath 1991: 127).

On 1 August 1974, the Nicobar Islands were elevated to an even higher status to become a separate district (Spandan 1999). The Union Territory of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands now comprised two districts: the district of Andamans, and the district of Nicobars. With this new status, the post of the Additional Deputy Commissioner was upgraded to the post of a Deputy Commissioner and Car Nicobar consequently became the district headquarters. As a result, the number of departments and administrative officers on Car Nicobar also increased, and to some extent on Kamorta as well.

In June 1981, a "Pradesh (or territorial) Council", for the whole of the Andaman and Nicobar islands, of 29 members was constituted (Das and Rath 1991:109). Up to 1992, two of these members were Nicobarese, one from Car Nicobar and the other representing the Nancowry and southern group of islands.[8] While the system still continues in the Andamans, from 1992 the Nicobars stopped sending their representation to the Pradesh Council. In its place was introduced the concept of the "Tribal Council" (also called "Island Council"). All important islands were supposed to form their own tribal councils while islands with smaller populations are merged with the one nearest. Members of a tribal council are the elected village captains with a chairperson to head it. Though officially a chairperson of a tribal council is appointed jointly by the Deputy Commissioner (Nicobars) and District Rural Development Authority (DRDA), this is only done after receiving nominations by the people of the respective islands. The length of tenure of the chairperson is not fixed and the candidate can continue to hold the post as long as the people do not raise objections.[9] A tribal council of an island functions like a mini-government and is the only official institution recognised by the Indian Government. Before introducing any development or welfare programme, .the administration must consult the tribal council of the respective islands. Alternatively, tribal councils can also make requests to the administration for implementation of projects specific to the needs of their islands.[10]

8 The first member of the Pradesh Council from Nancowry was Nishi Jim, and after his death in 1989, Ayesha Majid, who held this post until it was abolished in 1992. Ibrahim Ali Husain represented Car Nicobar in the Pradesh Council between 1981 and 1992 (Yusuf 2003).

9 Ayesha Majid has been the Chairperson of the Nancowry Tribal Council since 1992 (Majid 2002).

10 At present (2003), discussions are on between the administration and representatives of the various islands to introduce an autonomous "District Council" for the Nicobar Islands as a whole. Such a council would definitely make it easier for the Indian administration insofar that they would only have to deal with a single council instead of with the many island councils. However, the problem of a fair representation of members to this single council is still not completely resolved. The Nancowry leadership fears that since Car Nicobar has the highest population in the archipelago (i.e. two-thirds), the council membership would be heavily weighed towards Car Nicobar. With a two-third majority, Car Nicobar leadership could make decision for the rest of the islands without consulting anyone. Apparently, there appears to be a growing consensus that representation to the District Council could be on the basis of the number of villages, and not population (Majid 2003, Yusuf 2003).

In 1982, the post of the Chief Commissioner was upgraded to that of the Lieutenant Governor (LG) who now represented the President of India on the Union Territory of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. The system continues up to today with the post of Lieutenant Governor developing more in the direction of providing a quiet backwater posting with which to reward previous military, administrative and political services elsewhere.

One of the best ways to understand the economic and the environmental history of the Nicobars under the Indian republic is to review its "Five Year Plans" sanctioned by the Planning Commission. The Planning Commission was set up in March 1950 following a Resolution of the Government of India with the objectives "to promote a rapid rise in the standard of living of the people by efficient exploitation of the resources of the country, increasing production and offering opportunities to all for employment in the service of the community" (Planning commission website: http://planningcommission.nic.in/).

The first Five Year Plan was launched in 1951 and has continued every five years with the exception of two breaks: from 1966 to 1969 due to the IndoPakistan conflict, and from 1990 to 1992 due to the fast-changing political situation at the centre. During these years, the country was run on the basis of three annual plans. While the Five Year Plans prepared by the Planning Commission at the centre provide a guiding framework and philosophy of development for the nation as a whole, the different states of India have to prepare detailed plans for implementation, according to the budget allocated from the centre. The only difference between the various States of India and the Union Territories (UTs) is that the former must arrange their own financial resources for implementation of their plans while the latter are entirely financed by the central administration. The Five Year Plans for the Andaman and the Nicobar Islands were similarly prepared. In the following pages, some of the development and welfare programmes implemented in the Nicobars over the last five decades are described.

The Nicobar Islands, despite their remoteness, were in no way insulated from the ideology of Nehru concerning tribes. His ideas clearly found expression in the initial approach to tribal issues in the young nation's Five Year Plans. In fact they were in strict accordance with Nehru's ideas:

There developed one school of thought which held that the tribal population should be pennitted to live in isolation from other more organised groups, without even the interference of the political administration. There may be a good deal of justification for such a policy of non-interference; but it is not easily practicable when tribal life has been influenced by social forces from without, and tribal communities have reached a certain degree of acculturisation accompanied by the penetration of communications into the tribal areas and of social services for the bettennent of their lives. The conditions are now generally such that there has to be a positive policy of assisting the tribal people to develop their natural resources and to evolve a productive economic life wherein they will enjoy the fruits of their labour and will not be exploited by more organised economic forces from outside. So far as their religious and social life is concerned, it is not desirable to bring about changes except at the initiative of the tribal people themselves and with their willing consent. It is accepted that there are many healthy features of tribal life, which should be not only retained but developed. The qualities of their dialects, and the rich content of their arts and crafts also need to be appreciated and preserved" (First Five Year Plan 1951)

Further, the second plan laid clear emphasis on what Nehru called "psychological integration" of the tribal people in general. Following this approach, the plan endeavoured to impart to "the tribal people in all pafts of the country a sense of partnership and integration with the nation as whole" (Second Five Year Plan). The first decade in general gave priority to the building of roads, improvement of water supply, irrigation, development of agriculture, animal husbandry, cottage industries, and increased educational and medical facilities in tribal areas. Priority was attached to particular regions, especially those in the northeast and others such as those of Assam, Bihar, Orissa, Madhya Pradesh and Tripura.

With independence yet very new, the young nation was pre-occupied with consolidation and re-structuring of policies for basic sectors and for critical regions such as the North East. In such a situation, the Nicobar Islands received very little attention in the first half of this decade "except that the various departments of the Administration carried our their normal activities" (Second Five Year Plan). However, in the later half, the Indian Government followed a strategy of modernisation for the tribal population of the Andaman and Nicobar islands. Among the six tribal groups of this territory, the Nicobarese were soon singled out as non-primitive and "progressive in outlook" with "an urge for better standard ofliving" (Second Five Year Plan).[11] Most welfare schemes were therefore directed towards the Nicobarese. In addition, the Nicobarese comprised the largest tribal population of the Andaman and Nicobar islands.

11 The other five are the Great Andamanese, the Jarawas, the Sentinelese, and the Onges in the Andamans, and the Shompen on Great Nicobar. While the Jarawas and the Sentinelese "continue to live in complete isolation from the rest of the world", the rest, too, have very little outside contact, live in the "stone age" and do not accept any help from the administration (Third Five Year Plan).

Education was presented as the main thrust in development efforts. It is said that the experiences of Japanese brutality gave a strong impetus to Christianity (or brotherhood) and education in the Nicobars (Justin 1990). By the time India took over the islands, there existed five government schools and one middle school run by the church mission, all on Car Nicobar. "In keeping with the ideals of secularism of [the] country", it was decided to separate religious teachings from regular education. As a result, the imparting of religious instruction was stopped in the government schools. Instead the church organisation started vernacular schools for their purpose and these surprisingly had a higher rate of attendance than government schools (Mathur 1967: 145). Three more government schools were opened in a period of one year, bringing the total number of schools in 1948 to four with six teachers and 220 students. By 1955, the number of schools on Car Nicobar increased to six with 621 students - 175 of whom were girls. (Malhotra 1998:63). In additional to these, three primary schools were functioning in the Nancowry group (Second Five Year Plan). The school curriculum was, with a slight variation, similar to the education pattern of the rest of the country. Subjects taught were Arithmetic, Nicobarese, Hindi, Social Studies, General Science, Geography, History, Sanskrit, Drawing and English, with the singing of the national anthem as part of the school activity. Needless to say, incentives such as free books, stationery, uniforms, and other study materials were provided by the government (Mathur 1967:146).

Besides education, human health was the next major sector to receive the attention of the administration. By the end of the first Five Year Plan (1951-56), there were two hospitals and five dispensaries in tribal areas. The second Five Year Plan (1956-60) continued to emphasise education and two additional primary schools (one at Car Nicobar and the other in Nancowry) were opened. Two Nicobari students received stipends for vocational training in the Trade School at Port Blair. Further, a new hospital, a dispensary, a Community Welfare Centre and a Plant Protection Organisation for controlling pests and diseases in coconut plantations were introduced on Car Nicobar.

In 1956, a State Planning Commission for the UT of Andaman and Nicobar Islands was constituted with the Chief Commissioner (presently Lieutenant Governor) as the chairman, and the Member of Parliament, the heads of various departments, and a few nominated non-official members. Subsequent plans for the islands were drawn up by the State Planning Commission (Das & Rath 1991: 109). Education remained the focal area of development during the second decade as well. Two hostels at Car Nicobar and one at Nancowry were constructed to accommodate children from other islands who wished to attend school. Further, the middle school at Car Nicobar was upgraded to the higher secondary level. Two students having passed this grade in 1966 were sent to mainland India for education at the pre-university level. The government invariably encouraged higher education among the Nicobarese by sponsoring their studies at Port Blair or in mainland India. Already in 1964, the first Nicobarese to hold a BA degree from an university in mainland India was Edmund Mathew, who became Bishop of the Church of Northern India (CNI) for the Andaman and Nicobar Islands after the death of John Richardson. Edmund Mathews remained Bishop until his death in 2002 (Malhotra 1998).

In 1967, the number of students at the higher secondary level was an impressive 117 with a staff of thirteen (Malhotra 1998:64). In addition, two primary schools sprung up on the island of Teressa. By now there were four primary schools on Kamorta and Katchal each and a middle school at Nancowry (Mathur 1967: 144). A total of 420 merit scholarships and 23 hostel stipends were awarded to students in this period (Third Five Year Plan). This period also saw a whole new range of welfare programmes introduced by the government such as the establishment of "Community Welfare Centres", one each at Car Nicobar and Nancowry, a training centre in tailoring and garm~nt making for women in Nancowry, and on Car Nicobar, the appointment of a dance and music instructor, the appointment of a sports coach and the establishment of a "Labour Welfare Centre".

Economic "upliftment" was yet another area of concern for the government. In this respect, a two-fold approach was followed: improving the already existing sources of livelihood, and providing new ones. In view of the first, several hundreds of improved stud boars and birds (such as Rhode Island Red and White Laghorn) were introduced to "deserving and progressive families". However, the response to the new poultry was not as enthusiastic as had been expected (Mathur 1967:84, Fourth Five Year Plan). Another issue related to which the government showed concern was the way the Nicobarese lived:

The Nicobarese live in bee-hive shaped huts which are dark, dingy and illventilated.. ..There is overcrowding inside at night as all members of the household which consist of two to three families sleep in the same hut. This affects their health (Third Five Year Plan).

It was argued that the outbreak of poliomyelitis at the end of 1947 had been due to the poor housing conditions of the Nicobarese.[12] Since the "Nicobarese, as a class, are averse to taking loans from any source", the government offered subsidies to families for the procurement of building materials at low prices (Second Five Year Plan). This approach seemed to have worked and, if we are to believe the achievement report, some 450 houses were "improved" between 1961 and 1966 (Third Five Year Plan).

12 During November and December 1947, some 800 cases of poliomyelitis were reported in the Nicobars, 566 of which were paralytic and 118 fatal. However, the cause of this outbreak is largely attributed to movement of soldiers across the world in general during World War Two, and of British troops to the Nicobars in particular (Kohn 1995:226).

This period also saw progress in the area of health. Car Nicobar was equipped with a hospital with a capacity of 75 inpatients, an X-ray machine, and T.B. and infectious diseases isolation wards. A 20-bed hospital was also found at Kamorta headquarters, and dispensaries were opened in the villages Pilpillow, Kakana (Kamorta island), Kapanga, West Bay Katchal (Kate! island), and one each on the islands of Chaura, Teressa, Pulomillow and Kone (Mathur 1967:140-141).

|

|

Figure 8.1. An example of new housing style on Car Nicobar: a traditional house raised above a concrete hall |

To ensure the success of the various projects being implemented on t islands, the administration felt that:

A wide-spread understanding of the plan is essential for its fulfilment in a democr< society. The people should be able to see and realise the progress achieved in differ, fields. For enlisting public co-operation and participation in the various developm programmes initiated under the plan, it is necessary that the achievements are gi, wide publicity (Third Five Year Plan).

Consequently, twelve listening sets for the tribal areas and a "Publicity Mob Unit at Car Nicobar was procured and a cinema operator appointed" (Ibid.).

Already at the beginning of the Third Five Year Plan, Verrier Elwin, the Report of the Scheduled Tribes and Scheduled Areas (1960-61), remark upon the general effects of the development programmes on the aboriginal population:

Great Schemes for development are bringing and, by the end of the Third Plan, will have brought to every tribal village new ideas, new techniques and new contacts. Roads are everywhere urging their way into places which have hitherto been virtually inaccessible. Education, as it spreads, is revolutionizing the social and economic conditions of the tribal villages and is creating new demands as it generates new skills. In many of the hills and forests where the tribals live, there are vast resources 01 minerals, industrial raw materials and hydraulic power... In other tribal areas greal changes are taking place as a result of industrial development. The short-term invasion of the tribal areas, at any rate in the central belt, have, of course, an enormous significance. They raise the issues of rehabilitation, land possession, education. training and equipment.. .All these things will make demands for extensive psychological and physiological adjustments. They will affect the code of tribal life. and specially social discipline, the integrity of the family, the integrity of the village community (may even in some places cause the disappearances of the village community) the general culture and spiritual and aesthetic values. The new way of life may lead also to the spread of certain social vices which generally accompany urbanization (Report of the Scheduled Tribes and Scheduled Areas 1960-61, in Singh 1989).

In this decade, a new policy for the planning of tribal areas in the country was declared. This was called the "Tribal Sub-Plan" (TSP) and was evolved upon the recommendation of an expert committee set up by the Ministry of Education am Social Welfare in 1972. The new strategy aimed to ensure rapid socio-economil development and elimination of exploitation of the tribal population of India The most significant aspect of this strategy was the requirement that the flow of funds for the TSP areas be at least in equal proportion to the scheduled tribes of the State or the Union Territory. Following its adoption, the allotted expenditure of 0.51% in the Fourth Five Year Plan increased to 9.47% during the Eighth Five Year Plan (Tribal Affairs 2002).

During this decade, almost all of the development focus was on Car Nicobar. The popularity of education had brought the total strength of students to nearly 2,500 by the end of this period. In 1973, Cephas Jack became the first Nicobarese to hold an MA degree and was appointed as the Tehsildar (revenue officer) at Car Nicobar the following year and later promoted to Assistant Commissioner. Distribution of free books, stationery, uniforms, awarding of hostel stipends and merit scholarships continued to entice the Nicobarese into education. A district library was opened on Car Nicobar during this period. Sports and games were encouraged, in particular football, volleyball and athletics. The sports team of Car Nicobar started to participate in competition on the Indian mainland. Furthermore, music and dance received promotion with the establishment of a Kala Sangeet Institute.

|

|

Figure 8.2. District Library, Car Nicobar. |

Efforts to improve housing conditions continued through government subsidies and a review of the Fourth Five Year Plan mentions the improvement of ten houses and a community hall on Car Nicobar. Despite the disinterest of the Nicobarese, the distribution of high-breed poultry continued on Car Nicobar. The period also saw the beginning of a policy of improved agriculture and horticulture for the economic development of the Nicobarese. The agriculture department of the administration organised demonstration camps to encourage the Nicobarese to adopt improved methods of agriculture and horticulture. In this decade, the department gave 50 demonstrations of improved methods for raising coconuts, 35 for arecanuts, 12 for spices and 43 for planting maize.

In the 1960s, a scheme was drawn up to relocate 50 families from Car Nicobar to Katchal in the central group:

The total population of the Nicobari tribe is about 12,500, of which 10,000 (roughly) alone live in the island of Car Nicobar - 49 sq. miles in area. This small island is getting fast over-populated and not much vacant land and food is available to meet the growing needs of the people. The scheme envisages shifting of 50 families from Car Nicobar to the Island of Katchal which is thinly populated, for permanent settlement. An area of 500 acres would be allotted for joint coconut fanning (Second Five Year Plan).

For some reason, the Car Nicobarese refused to move to Katchal and finally after a lot of persuasion involving tribal leaders, some 100 families were relocated to Little Andaman instead. The settlement was called Hut Bay, where each family was allotted ten acres of land (Review of the Fourth Five Year Plan).13 In 1975, a special cell called the "Directorate of Tribal Welfare" (DTW) was established for the administration of the welfare programmes in all tribal areas in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. As part of a publicity campaign for government programmes, tribal representatives were taken to mainland India for Bharat Darshan (a tour of India), where they were exposed to different lifestyles and cultures.

13 According to another source, 165 families were resettled upon Little Andaman (Spandan 1999:20).

The fourth decade (1980-1990) [14]

14 Based on the fifth and sixth Five Year Plans.

By now, a strong modernisation process in the Nicobars had taken root. The motor of development was Car Nicobar with a high rate of education and as the first recipient for all development programmes when compared to other islands. By 1987, more than 3,000 students were enrolled in schools at Car Nicobar, of which nearly 100 students were ready for university education or jobs (Malhotra 1998). This compelled the opening of an "Employment Information and Assistance Bureau" on the island. Incentives such as free books, stationery, stipends and scholarships continued as before.

Under the economic development programmes, a new poultry farm at Car Nicobar was established and later expanded within this time. Furthermore, 300 improved poultry birds were distributed and more than 50,000 existing birds were vaccinated free of charge. A new pig-breeding farm was also established at the cost of the government. A mobile veterinary van and two new buses were put on the road. Several Nicobarese were sent to the mainland to gain up-to-date knowledge on poultry and pig rearing. In the view of the administration, "the whole pig husbandry of the Nicobarese is most unsound. Either the pig is eaten before it has attained its full growth, or even after it is fully grown and is not going to increase further in weight, it is allowed to exist for many years till some big feast takes place and pigs are required to be killed" (Mathur 1967:82).

This decade also saw a phenomenal drive to introduce improved agriculture and horticultural practices to the Nicobarese. A total of

125,740 coconut seedlings, 118,572 arecanut seedlings, 60,693 fruit plants, 33,460 pineapple suckers, 42,000 banana suckers, 14,750 coffee seeds, 2,600 cocoa seeds, 81,866 spice seeds (pepper, cinnamon, cloves and nutmeg), were distributed. With this, a total of 877 hectares was brought under new agriculture.

|

|

Figure 8.3. Hospital at Car Nicobar, with Nicobarese doctors (except second from right) |

In addition, a total of 7,570 hectares also came under rice cultivation, tuber! root crops, pulses, cashew nuts, oil and vegetable seeds. Further, nearly 31 tonnes of pesticides, 149 tonnes of fertilizers and three tonnes of barbed wire arrived.[15] Needless to say, the whole programme was accompanied by seven extensive onsite demonstration camps, while the training of ten Nicobarese on the mainland was funded.

15 The statistics presented here are reported as progress made in the district of the Nicobars as a whole but field interviews suggest that most of this work was carried out on Car Nicobar.

To enable the Nicobarese to take better advantage of fish resources, 3 additional motor-boats were provided to Car Nicobar at subsidised rates fror the government, and several youths received training in mechanised fishing. A fish culture pond with fish seeds and necessary fishing equipment was established on Car Nicobar. With a view to improving the economic condition the government introduced a new alternative for the Nicobarese. The large amount of coconut husk available on these islands inspired the administration to establish a training centre for coir processing technology. In this period, seven dozen tribal youths received training in this sector and two of them were als sent to the mainland for such training.

In this period, the process of electrification of villages assumed a new dimension. Six villages in Car Nicobar and nineteen in the Nancowry group (14 alone in Katchal) were electrified. Besides this, six power generation sets were installed on Chowra and Teressa together. Furthermore, existing power generation capacity for Kamorta headquarters was greatly enhanced. Health services improved with the upgrading of the existing hospital on Kamorta and Car Nicobar. Operation theatres on both islands were equipped with air conditioners while Car Nicobar received a new ambulance and saw the opening of a new health sub-centre. To reduce incidences of malaria, mosquito nets were distributed with a 50% subsidy of the cost.

|

|

Figure 8.4. Ayesha Majid, Chief of Nancowry,

giving out awards to school children |

In general, the scheme for the improvement of houses was expanded under the Indira Awas Yojna (Indira Housing Scheme), and the construction of sanitary toilets on several islands was commissioned. Some 20 km of road was added to the Nicobar Islands in general, and jetties at Car Nicobar, Kamorta and Katchal islands were expanded. Needless to say, the publicising of achievements, dissemination of information on these welfare programmes and the widening of the horizons of the Nicobarese continued on a even larger scale.

The last decade witnessed continued extension of infrastructural facilities for all sectors in tenus of welfare and development. A review of the Eighth and Ninth Five Year Plans revealed that a total of 5,334 hectares of land came under agriculture/horticulture in tribal areas, most of which planned to be on the Nicobar Islands. In addition, 168 improved-breed as well as milking animals and 371 improved-breed poultry were distributed.

The decade produced even more educated young people from the island of Car Nicobar. Most of these found themselves serving mainly as teachers while six of them (one, however, from Chaura) qualified as doctors (two of whom were women), and several joined the local administration as government clerks.

A waradi (1996) provides a comparative view of the level of development on all the island of the Nicobars by the middle of the last decade. However, Table 8.1 summarises the level of development and infrastructure existent on Car Nicobar on one side, and ofNancowry, Kamorta and Katchal on the other.

Table: 8.1. Infrastructure and Facilities Compared Between Car Nicobar and Nancowry Islands

While in terms of absolute numbers the infrastructure facilities are higher on Car Nicobar, the per capita service of the same is higher for Nancowry. But one may not regard this as a measure for the development index. Since the availability of services and welfare schemes have always arrived first at Car Nicobar, the quality of these services is presently much better than that available on Nancowry. Higher population, complex social organisation, administrative headquarters, early access to education and other welfare programmes have led Car Nicobar to occupy a higher hierarchical position in the archipelago. The following chapter entails a more detailed description and explanation of Car Nicobar's rise to prominence over the last five decades.

A World System perspective of the Nicobar Islands 1756-2003

A sweep through the last 250 years of economic history reveals that the Nicobar Islands, despite their remoteness and entry restrictions, are now firmly integrated into the world economy.

Their incorporation into the world economy, as we have seen, has not been without consequences. It might appear, on the one hand, that the Nicobarese have "progressed" beyond their subsistent economy. However, on the other hand, we find that their place in the global economy has so far been prejudicial to their well-being. This precarious situation has been recognised by the Nicobarese themselves, with the effect that some have been impelled to seek redress through the courts in order to redirect the process towards a fairer deal.

Nonetheless, we know that the Nicobarese were not mere victims of the influences around them. They were very much actors, at least until recently (2003) when the entire process rebounded to their disadvantage.

My foremost endeavour in this monograph has been to reconstruct the hitherto unknown economic history of the Nicobar Islands (reproduced on this web-site only inparts). To bring together this body of information on the Nicobars has in itself been a herculean task and, in my opinion, worthy of a monograph. However, the task does not end here. The material presented here is now available to all scholars, including myself, who wish to engage in lengthy analyses within their disciplines and scientific discourses. In the course of this chapter, I shall point out the areas I intend to explore further in my future work.

|

The material reproduced here is part of a much larger corpus of material collected before and during 2003 by Dr. Simron Jit Singh. I received my copy of the printed book from the proud author in October 2004 - only two months before the Tsunami of 26 December 2004 struck. The Nicobar islands have suffered more deaths as a percentage of their total population and far wider destruction in relation to their size than even Sumatra did right next to the epicentre of the 26 December monster earthquake and tsunami. In view of this tragic background, the quiet moral strength coupled to keen intelligence, a wry sense of humour and an openness to new experiences displayed by the six Nicobarese visitors attending a conference in Vienna in September 2005 (see A&N News) made a tremendous impression on all who met them. Those were not broken people from a shattered chain of islands. As Dr. Singh, a few lines above, has noted, the Nicobarese are "firmly integrated into the world economy despite their remoteness". A civilisation (and that is not too strong a word for it) capable of such a feat will not be destroyed even by the largest recorded tsunami in history. The Nicobarese visitors to Vienna have made it very clear that they are grateful for the help and advice proffered to them but they have made it just as clear that they, and only they, can and will decide what help they need and how their devastated archipelago is to be rebuilt. Advice yes, interference no. The shared tragedy has also bound the people of the islands closer together as survivors. The age-old little jealousies between the islands is said to be gone. Car Nicobar is not included in this remark, but Car Nicobar has always been on another planet but even that island seems to have moved a little closer to the rest. The very fact that a group of six Nicobarese could travel to Vienna (rather than have bureaucrats from New Delhi go on their behalf) is almost a cultural revolution on its own. The Nicobarese show every sign of taking their fate into their own hands. If that is indeed so, the tsunami has not only brought death, it has also bought the hope of a new beginning and cooperation. There is also talk that India will reward the maturity-in-adversity that the Nicobarese have shown during the emergency by giving the islöanders much more internal political responsibility and autonomy. Parts of Dr. Singh's book may have to be revised because of the tsunami. The texts we reproduce here, however, are concerned mostly with Nicobarese history and historical trade relations and need no post-tsunami revision. The chapters reproduced here provide the only easily accessible overview of the islands history. You may have noticerd that all sources older than a few decades are outsiders (including mainland Indians). There is no history of the islands from the point of view of the Nicobarese and there is unlikely to be one soon. Even if the Nicobarese had a written tradition, the tropical climate alone would have destroyed most of it. What could still be collected - by the Nicobarese themselves - is tales and traditions that are still alive. At the risk of repeating myself and being boring boring boring, I would like the re-state the need for some archaeological exploration in the islands. George Weber |

[ Go to HOME

] [ Go to HEAD

OF NICOBAR CHAPTER

]

Last changed 12 March 2006