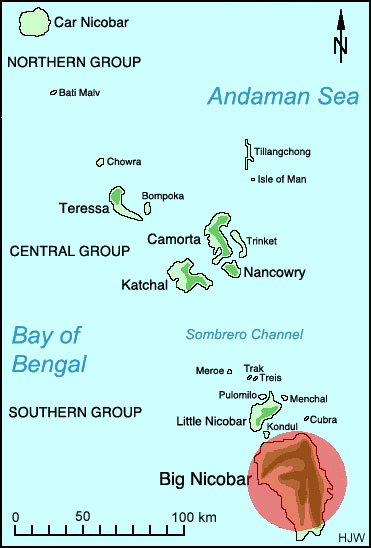

Location of Great Nicobar island

The Nicobar Islands

The Shompen People

by George Weber

|

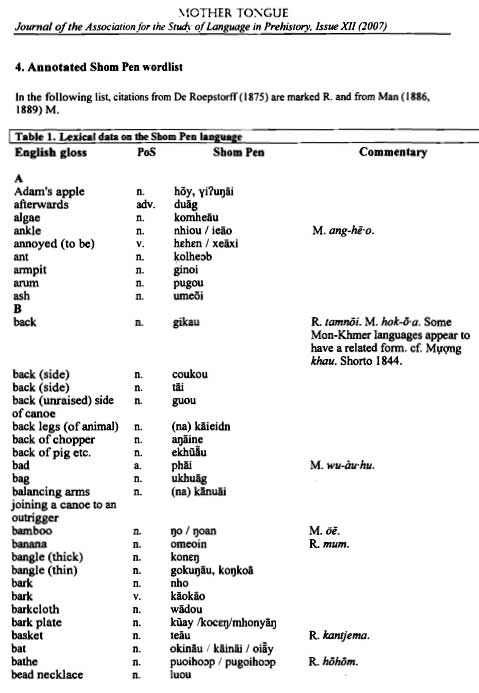

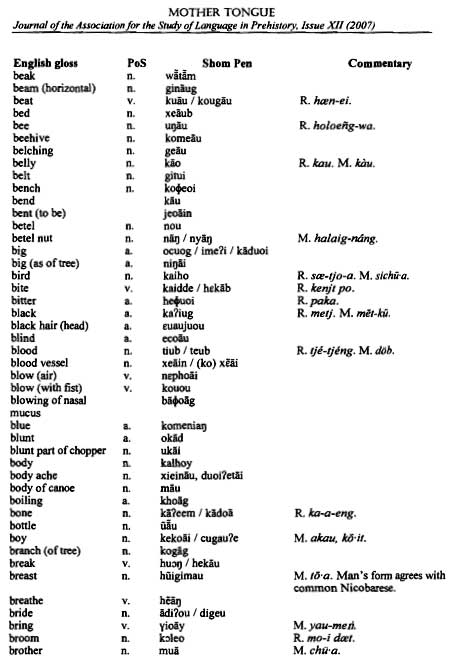

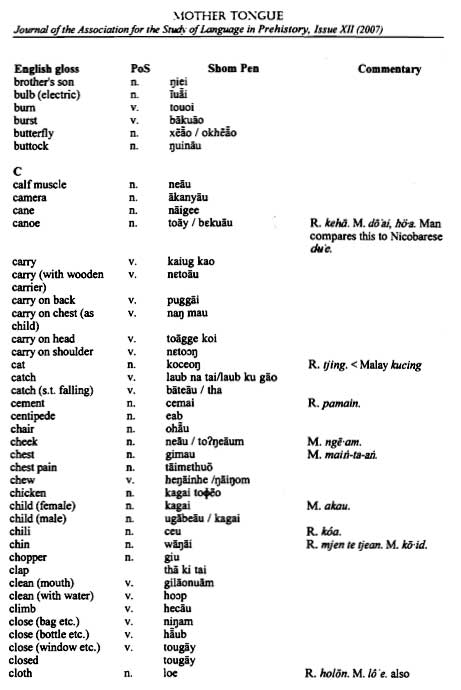

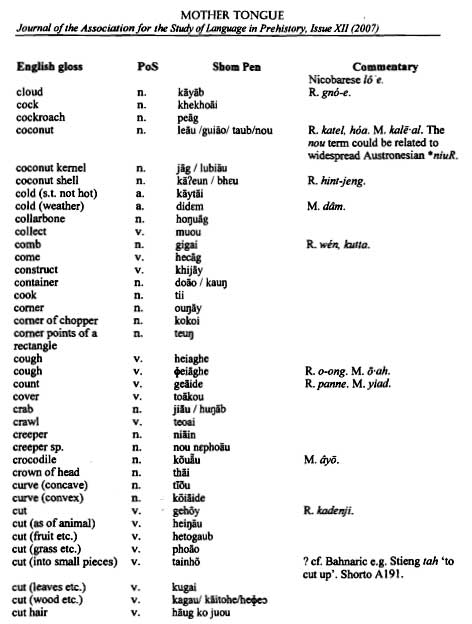

Table of Contents 1. Geography and Distribution of the Shompen 2. Röepstorff: an early search for the Shompen 4. The Shompen Language (by Roger Blench, 2007, reprinted from Mother Tongue, Harvard University) |

Most of the inhabitants of the Nicobar islands who are not recent immigrants are Nicobari. Despite some differences in language and culture between the inhabitants of the various islands, the Nicobari are obviously and clearly one people.

Besides the Nicobari, however, there is a small group of tribal people living largely hidden lives in the interior of Great Nicobar - and only on Great Nicobar: the Shompen. It is easier to say what the Shompen are not than what they may be.

The Shompen are neither Nicobari nor are they related to the Andamanese Negrito. They speak a language or possibly several languages that is (or that are) quite different from the Nicobari languages although they seem to be related to it. The Shompen represent the original population of the Nicobar islands, predating the arrival of the Nicobari by many thousands of years.

Sadly, virtually no archaeological work has been done on Great Nicobar so far.

1. Geography and Distribution of the Shompen

|

|

Location of Great Nicobar island

|

|

|

Great Nicobar and its populations

reddish area: concentration of Nicobari population in the 1990s. red dots: main Indian settlements black dots: Shompen settlements black-grey circles: abandoned Shompen settlements black line: East-West Road

Shompen groups in the late 1980s 1. Alexandria River group (7 persons, 2 households) 2. Dagmar River group (10 persons, 1 household) 3. East-West 24/27 km group (11 persons, 4 households) 4. East-West 28 km group (15 persons, 5 households) 5. East-West 35 km group (24 persons, 9 households) 6. Galathea River group (5 persons, 3 households) 7. Kokyon or Loni-E group (19 persons, 7 households) 8. Laful (Tendrin Tikri) group (2 persons, 1 household) 9. Laful (Trinket) group (22 persons, 7 households) 10. Jhao-Nala (Rangathan Bay) group (19 persons, 5 households) |

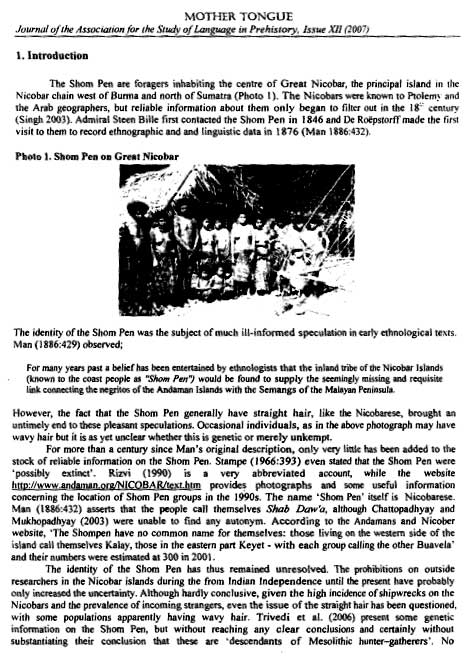

The Shompen are "the other Nicobaris", an enigmatic tribe living in the densely forested interior of Great Nicobar. There number has been roughly estimated at 300 in 2001. Very little is known about them. Recent unpublished genetic studies have indicated that the Shompen have different origins from the "ordinary" Nicobaris, although both groups have Mongolid ancestry .

The ancestral Shompen seem to have come to Great Nicobar from Sumatra, more (maybe much more) than 10,000 years ago. The "ordinary" Nicobaris, on the other hand, came from the east, from mainland southeast Asia many thousands of years later than the Shompen. There is some genetic and linguistic evidence that the two groups mixed to a limited extent. Earlier suspected links to Negrito populations, however, have not been found. A peculiarity of the Shompen discovered in 1967 was that all of 55 individuals then screened turned out to have blood group O in the ABO system.

While the Nicobaris were seafarers and traders and were in contact with the outside world, the Shompen, at least after the Nicobaris had arrived, were inland people, living hidden lives in the dense jungles of their island with limited contact to the outside world, including the Nicobari.

Certainly, this was the situation when the first western scentific investigators arrived in the 19th century. The Shompen were never numerous and there is genetic evidence of inbreeding and population bottlenecks among them. That their isolation was not complete, however, is proven by the presence of Portuguese and Malay loan words in their language. The Shompen language is thought to belong to the same language family as Nicobarese (i.e. the Mon-Khmer branch of the Austro-Asiatic family) and that it is related to Nicobarese - but is a separate language and not just a Nicobari dialect.

The earliest reference to the existence of the Shompen dates from 1831 and the first recorded visit of an outsider to them of 1846.

The Nicobaris living on Great Nicobar call the Shompen Shamhap. Indeed, "Shompen" may be a British mispronounciation of that name. The Shompen have no common name for themselves: those living on the western side of the island call themselves Kalay, those in the eastern part Keyet - with each group calling the other Buavela.

Their way of life in the interior of their island has protected the Shompen to some extent from the Tsunami of 26 December 2005 - unlike the mostly coastal Nicobari and Indian populations who suffered terrible losses.

2. Röepstorff: an early search for the Shompen

X Mrs Röepstorff was of Danish ancestry, like her

husband. . She took over the administration of the islands

after the murder of her husband. Mr Röepstorff was in charge of the British

settlement in the Nicobar islands when he was murdered by a

havildar (native sergeant) in October 1883.

The following article by F.A. de Röepstorff was originally published in The Geographical Magazine, 1 February 1878, pp. 39-44.

|

The Inland Tribe of Great Nicobar: the Shompen by F. A. de Röepstorff

In a paper on the Nicobar Islands, in this Magazine (The Geographical Magazine, February 1875), I mentioned that there were tribes of inland people in the Great and Little Nicobars.Since writing that paper I have had an opportunity of visiting these islands, and that visit, with its results,is the subject of the present article. We have old reports of inland tribes at the Nicobars, and ethnologists came to the conclusion that they were Negritos, although no one had actually seen them. As the Andamans are peopled by such curious dwarfs, and as they are also found in the Malay Archipelago and Philippine Islands, it was considered desirable that a link should be found at the Nicobars connecting the Andamanese with the other Negrito tribes. The inland race, being likely to be of a lower stamp than those who had driven them away from the coast, were set down as being Negritos, and had been spoken of as such so often that it had nearly come to be considered as a fact that Negritos were to be found at the Nicobars. That there were people inland was quite certain. The Nicobarese spoke a great deal about them. The Rev. Mr. Rosen made the last attempt at colonising these islands in 1831-34. In 1846 the Danish corvette 'Galathea' visited the Nicobar Islands, on her voyage round the world, and among the parts explored was the river (or creek) that opens out into the Galathea Harbour, in Great Nicobar. The expedition heard a great deal from the coast-people about the tribe living in the interior, who were said to be Orang-utangs*. It was also reported that they had neither huts nor canoes, and that they eat snakes and frogs, caught by magic spell. Although it was quite evident that the coast-people gave a very exaggerated description of this unknown tribe, they had, however, succeeded in awakening so much curiosity that an exploring party was formed to go up the river (creek), and, if possible, to communicate with them. *This means simply "men in the forest"; and I think that in this case the name is not inappropriate, and need not be taken to mean "monkeys". It must be remembered that no individual could speak the language of the coast-people, and that the Malay language, which was used, was a foreign lauguage to both parties. The expedition started on the 9th February 1846. The boats of the corvette were used, manned by European sailors. It was with great difficulty that progress was made, for every fallen log had to be got rid of, and the hot tropical sun was very trying to the men, so that the rate of progress in eleven hours was only from i6 to 20 miles. The narrativet records that they reached a spot "where the river turned at a right angle easterly, and where a large jungle-covered hill steeply overhangs the river. Behind this hill the river forms a little bay, and in this we found three or four canoes, fastened near the land. Having landed, we climbed the hill slope, and found the place carefully railed off from the river side. Inside this rail, which enclosed the whole hill, lay seven or eight empty huts. On the hill slope lay a fallen log, with its crown resting on the other side of the valley, where the canoes were lying, like a bridge in the air. From the care with which the place had been railed off, one might suppose that these poor savages were afraid of being attacked, and had kept this line of retreat open." [This alludes, I believe, to the fallen log]. "But of whom were they afraid? Who were their enemies? Captain Aschlund, who had visited the same spot the day before, had found that it had been just evacuated, and that fire was still burning on their cooking-places. They could not possibly know of our approach, so that it could not be us they feared. It was hardly either against the coast-people that they wanted to defend themselves, for it was quite apparent that these two peoples, although living on the same island, which is only 28 miles long, and 12 to 16 miles wide at its broadest part, were quite ignorant of each other, so that the coast-people spoke of the inland tribe as forest-demons, who lived in the trees, ate frogs and snakes, which they caught by supernatural means, and altogether resembled very much the animal whose name they gave them, namely, Orang-utangs. They assured us that they had neither houses nor canoes, but the first things we met were canoes and houses. Against whom were they thus keeping on the defence? Was it possible that war, with its wretchedness, had found its way into the centre of the jungles of this little island, and that the couple of hundred people who live here should try to destroy each other in this little place? All these questions and conjectures forced themselves on our minds as we wandered about in this little deserted village, whose only inhabitant we found enclosed in a sort of prison, formed of a couple of logs, with sticks between. This was a pig, who seemed famished, and, to judge from this fact, the inhabitants had probably not been there for several days. That this establishment had recently been formed was evident from the fresh state of the palisading, and the poles on which the huts rested. We all agreed that the inhabitants must be in a higher state of civilisation than our friends, the coast Nicobarese, would allow them to be. It is true that the huts were the most wretched specimens we yet had seen; there was hardly space in them for two people to sit, much less to lie in; but yet they were huts, and built on the same principle as those of the coast-people, namely, raised from the ground on poles, which mode of construction is always used by Malays when in swampy places. Several were merely small sleeping-platforms, with one side supported by the trunk of a tree, and roofed over with dhunny and rattan leaves or sheets of bark. Such a sheet of bark also formed the substance of their cooking-pot, which stood on a stand formed of four little sticks, with cross sticks, under which the fire was laid. We found some wooden spears, and some pieces of cloth pressed from the cettis bark, but they were very ragged. On the ground were thrown some used caldeira fruits, and in one of the huts we found a piece of prepared pandanus bread. Finally, we found in the forest, close to the railing, a big tree that had newly been felled, from which we concluded that their tools must be pretty good. Everything seemed to show that the inhabitants of this establish ment were of the same kind of people as the coast Nicobarese." Shortly after landing a most terrible thunderstorm overtook the expedition, and the violent rain, the noise of the thunder, the lightning, and the crash of falling trees, all combined to make the visit to this village an event not easily to he forgotten by the Danes, and many of them suffered very severely from jungle fever when they got out to sea. In February no rain can be expected, as it is the height of the dry season. The above visit of the Danish officers to the abandoned village was the only authentic information that existed of the interior of Great Nicobar, and it remained undecided who the owners were of these huts. In January 1871, on duty in HMS Dryad, I visited the Galathea Bay; but as the work of erecting a flagstaff and taking possession was performed in a day, and the Commander could not delay our departure, I had no chance of visiting the above-mentioned village. Ever since that time I have been most anxious to get another chance to visit Great Nicobar, and solve the mystery of the inland people.From the Nicobarese, near Nancowry Harbour, I had made all sorts of inquiries, but without any great result. They had all heard about these people, but had never visited them in their homes. Their name is Shom-Baeng. 'Shom' means 'tribe, e.g. Shom-pu, a 'man from Car Nicobar'. Their specific name is thus Baeng or Beng. In 1872, some coast-people on a trading visit to Nancowry came to my house, and among them was a young man who was said to be by birth a Shorn-Baeng, and who had lived with them from boyhood, the only connection he had kept up with his family being an occasional meeting with his mother in the jungle. As he knew his own tongue I was very anxious to get as many words from him as possible. This, however, was no easy matter, for never having before seen a European, he was very much frightened. What especially disturbed his peace of mind was our old elephant, who was bathing when he landed. For a time I succeeded in quieting him, and we proceeded very satisfactorily until sunset, but he and his friends could not be prevailed upon to remain any longer; nor did he ever return. He was a big, strong youth, nearly of the same build as the people of Nancowry, but perhaps a shade lighter in complexion. The most prominent feature was, however, his small oblique Mongolian eyes, and the circumstance that the back of his head had not been flattened, it being customary among the coast-people to flatten the heads of their little children. It struck me at once when I saw him that he resembled the men from Schowra, a little island to the north of Nancowry. Although I was convinced that these people had spoken the truth with regard to the boy, still I was very anxious to verify this curious discovery that the inland tribe at Great Nicobar is of Mongolian and not of Papuan origin. At last, on the 1st April 1876, at 4 p.m., I started on my trip southwards from Nancowry, in a fine open cutter, with a strong convict crew - eleven lifers - and four free policemen as a guard, and with two Nancowry guides. It was rather late in the season, for the SW monsoon might be expected in a few days, and clouds had occasionally warned us. We had no compass, but steered by the stars, and my two guides had to take turn with me at the helm. It was a lonely night, the temperature mild and agreeable, and above us was the clear, starry sky, and a little moonlight. The convicts, whose life in these parts is such that they could tell their friends afar off many a wonderful tale, sat for a long time staring at the new islands we were approaching, till they gradually fell asleep. The wind was very steady, so that after a while our steersman was the only one awake. During the night we passed the little islands Meroë, Track, and Treis. Early in the morning, Captain Johnson (our guide) brought us to anchor in a sandy harbour on all sides surrounded by coral reefs, near Little Nicobar. As the cutter could not land we had to fire a gun, which very soon brought a couple of canoes to our assistance. It is customary in the Nicobars, where inns are unknown, that the stranger selects a house as his home; and whenever he returns to the village he invariably goes to the same house, and is treated with the greatest hospitality. This house is his gni lancije, and his host will claim the same privileges, if he comes to his place. In every village I have visited I have such a host of friends, who are at all times prepared to receive me, and I should give great offence were I to go into another man's house. After having chosen my host (gni lancije), we settled in his house, and in an hour everything was snug ashore, and the men set-to cooking. Then arose a difficulty, which threatened to put a stop to our expedition. Before starting I had filled four water-casks at our well in the settlement, because I was afraid that bad water might give the men fever, and this I had done by Brahmins. Now, the men refused to use the water, declaring it to be against their caste to do so. This, I felt pretty certain, was a trick. We found some little waterholes in the jungle, and I had to give the men leave to use this water, although it looked very nasty. In the afternoon, I paid a visit to the little island Treis, one of the places where the magnificent Nicobar pigeon breeds. Next day we repeated the visit near sunset, as the pigeons are more easily got at about sunset and sunrise. After shooting, we all slept in the cutter. Next morning we returned, and made ready for the journey to Great Nicobar. My guide advised me to go to the little island Pub Condul (Nic Lamongshe). We spent the night on the way, and a charming voyage it was. Current and wind, stars and moon, all favoured us, and we arrived early in the morning at Condul refreshed by a good night's rest. Our reception was enthusiastic, and the natives crowded on board, and in a very short time a house was cleared for my reception, and another for my men. As my crew consisted of convicts I had always to be very careful that they did not seize the boat and escape, and for this reason a sentry had to be placed over the provisions day and night. Meeting with such a cordial reception I at once profited by it, and told my host that I had come to see the inland tribe, at which they pulled very long faces; whereupon I at once declared that I did not intend stirring until I had succeeded. On hearing this, my hosts retired; and after a long consultation, told me that they were willing to do their best. There was at that time a man and his son near the coast, where they came to barter for tobacco. They assured me that he would be so frightened at seeing me that he would run away, but they would send some messengers before me with presents to prepare him. Accordingly some men set off at once with some tobacco and red cloth as peace offerings, and after taking breakfast I set off with my host and another man. Just as we were departing, my orderly, a fine Sikh, came up to me and begged to be allowed o follow me, saying that, as he was responsible for my personal safety, he would like to be with me in case the savages attempted my life. So he was allowed to come, but we went without any guns. A journey of six miles in a canoe, with a tropical sun over the sea, when it is quite smooth, and there is no breeze, is very trying; consequently, we all had to take our turn at the paddles. I tried to while away the time in repeating some of their fairy tales, which my savage friends enjoyed very much. They repeated each sentence, and explained the meaning to each other. They are like children, and I had to repeat one of the stories twice. The sun was very hot, and the last part of the journey we were silent. We passed some large, steep rocks, in which are found edible swallow nests, and small valleys, where cocoa-nut trees and casuarinas gracefully grow on the alluvial soil behind the green bushes on the coast. At last we entered the Ganges harbour. A little rock island surrounded by coral reef forms the breakwater to this small but very safe harbour, and here I noticed paddy birds (Demi egretta sacra). Inside the harbour were still visible the marks of a violent earth- quake that happened herein 1846. The last remnants of the trunks of trees, which with their soil had sunk into the sea, still showed above water, and as we wound our way quite noiselessly between the dead trees into the bay, it made a very dismal impression on my mind. At last we touched at some rocks, where we found the canoe of our ambassadors. My host now produced a red cloth to put over my dress, otherwise I would frighten the Shom-Baeng; he then insisted on my taking off my hat, shoes and stockings, and although I tried to dissuade him, he would have me do it. As I had knickerbocker socks on, you may imagine that I was in a most uncomfortable position, a burning sun above, rocks covered with little sharp-edged oysters below, and surrounded by sandflies and mosquitoes. Quite silently we wandered along the rock edges, and when we reached the inmost part of the bay we came to a mud bank laid bare as it was low water. We waded across. On the other side was a little shed, if a little roof made of dhunny leaves on four poles may be so called. There we found the men that had gone before me, and they told us that the man had recently been here with his son, but had run into the jungle. I begged of them to run after them, as I felt this to be a most cruel disappointment. My host, however, told me to sit down, and proceeded a short distance into the jungle. Presently I heard him calling out in all directions. After a while somebody answered, and then followed a long parley, of which I did not understand a word. I dared hardly breathe, for I had made up my mind that, whatever happened, I must see this people, and now I was so near them, and, perhaps, yet so far from accomplishing my wishes. At last my host called out to me "Come quick, and bring some presents." I rushed off wildly in my eagerness, but it was through a pandanus copse; a lot of the sharp-pointed leaves lay on the ground, which cut my legs badly as I ran. In one hand I carried a packet of tobacco, and a piece of cloth in the other. I came upon them near a little stream. The Shom-Baeng stood on the other side of the water, and was still doubtful in his mind. However, we prevailed on him to come across, when he snatched the presents out of my hand as a wild animal snatches food. My host walked off with him, while I went into the stream with an old man of our party, who came up to dress my little wounds, caused by the pandanus leaves. We remained here purposely for some time, to give Shom-Baeng time. When I returned to the hut, I found him leaning against one of the poles, staring at me, and watching my every movement, as if he feared that I was going to throw myself over him. He was, as I had expected, a Mongolian, with small oblique winking black eyes, such eyes as the frightened beast has. The coast-people have brown eyes. He could speak slightly the dialect of the coast-people, and they a little of his language, and also the Nancowry dialect, and so we got up in this roundabout way a conversation. He denied that his son was with him, at which I said nothing, although I knew that the boy could not be far off. He stood 5 ft. 8-1/2 in.; and, for comparison, I may add that a full-grown Nancowry man stands 5 ft. 6 in. to 5 ft. 9 in., an Andamanese Negrito 4 ft. 9 in. to 5 ft. 1 in. From this it will be seen that he was by no means a little man. He was slenderly built, and had a well-formed head. His mouth was very different from that of the black coast-people, who have enormous protruding front teeth, that increase in size on account of the quick-lime and chavica-leaves which they eat; his teeth were small,but black, his lips small and well formed. He told me that his people chewed betel nuts (areca), betel-leaf(chavica), and quick-lime; but that, as they did not know how to bum lime, they had but very little of it. This was, I suppose, the reason why his teeth were not bigger. He was greatly amazed at seeing me write, and had evidently never heard of such a thing; for when it was explained to him that I was putting down what was said, he laughed, and gradually recovered from his first fright. He told me that his people neither eat the python nor monkeys. I asked about this, because the coast-people invariably asserted that they did. He related that they had gardens, and that the women wore a skirt made of bark. His head was not flattened behind, and his jet-black hair fell wildly over his face, cut straight off near his eyes.His forehead was high and well formed; his nose hooked, but flat below. He told me that they did not know how to make pottery, but used vessels made of betel bark, and he showed me such a one, which stood on two little stones, in which lay the remains of his last meal, viz., two half-grown paddy birds, which he assured me tasted very well. His people did not know how to make canoes, and he had bought the one he had from the coast-people. He told me he had got the paddy birds from the little rock, which I noticed at the entrance to the Ganges Harbour. This proved to me that he could paddle a boat. While we were talking, a pig came up and stood quite close to us. It seemed quite at home, and he told me that it was a pet of his; it had followed him all the way from his village - two days' journey. The pig looked like those found near the coast. He told me that his people do not use bows and arrows, but that they used spears. I begged of him to take me to his village, but my host and the other people opposed, and made him afraid. They were evidently themselves afraid that I should take them there. The Shom-Baeng promised, however, that he would go to his place, and bring me a spear of each kind, some produce of his garden, and a piece of cloth, as the women use it. He said that he could not make the journey in less than four days, and so four knots were made on two little sticks; we kept the one, and he the other. We then departed, and when we returned to Pulo Milo, my guide was very much displeased at the arrangement. Captain Johnson shook his head, and declared that we should have bad weather before we returned. As this possibly was my only chance, I would not throw it away, and made up my mind to wait the four days. From this time, however, everything went contrarily; my stores were out, and we had only fowls and rice to live on. The four days were spent in collecting insects, shooting, visiting the villages; and when the 9th of April arrived, we were all very glad to depart. I bought a new canoe, and presented it to my guides, who were delighted with it. We proceeded in the early morning towards Ganges Harbour, and anchored the cutter behind a point, and went up to our friend in our canoe. As it was high water, we were able to come right up to his hut. The first thing that met my eyes was his pig, which stood at the landing-place, and I saw the Shom-Baeng peeping out from behind a bush. He received us very friendly, and had brought his little brother with him. He gave me three spears one made entirely from areca wood, exactly like the one found by the Danish expedition in the village on the Galathea river, and two spears, with small iron heads, very badly made, and quite different from those used by the coast-people. He also brought a piece of the cloth which the women use, made from the celtis bark, which is beaten out, and really resembles cloth. I have often met with it in the other Nicobar Islands, and was always told that it came from Great Nicobar, where it was made by the Shom-Baengs. He also brought me an enormous yam and some gunia, the size of the former proving a high state of agriculture. He told me that he had spoken with his people, and informed them that I wanted to visit them, which they were willing to allow, providing I brought my wife. I explained to him that this might happen some day, but I also told him that she would have to be carried there, as she could not walk such a distance. I gave him some presents for himself and his wife, and we parted as friends. I learnt from the coast-people that there were three tribes of these Shom-Baengs, one at the northern part of Great Nicobar (the man whom I met belonged to this one) another on the west coast. This tribe, I was informed, did not live very exclusively; but they often visited the coast-people, and had even come on board ships in quest of tobacco, of which they are very fond. The third tribe lived near the Galathea river. The coast-people also asserted that they did not understand how to make canoes, but had little huts. The coast-people did not know anything about the 'Galathea' Expedition, and thus confirmed in every detail that the village visited really belonged to the Shom-Baengs. The result of my visit was as follows:- I met a man of the northern tribe, that he produced a spear like the one found on the Galathea river, that he cooked in such a vessel, made of bark, as was found there, thus identifying himself as belonging to the same people. He was a tall man of about the same height as the coast-people, but a shade lighter in colour. His Mongolian eyes and prominent cheek-bones were remarkable. The possibility that this inland race should be a mixed one of Negritos and coast-people is not however proved.I asked him most particularly whether there were any men of such a description among them, which he denied. He was not of any mixed breed related to Negritos.I mention this possibility because we know of suchmixed races elsewhere.* *Jagor (The Philippine Islands). Senor Ynigo Azaola (letters published by St. Bille). Thus, I hope, by what I have seen and what I know, together with what the 'Galathea' Expedition relates, to have exploded the theory of Negritos being found in the interior of Great Nicobar. In the account of the 'Galathea' Expedition, Admiral Bille mentions that he found boats at the village of the same construction as those of the coast-people, and he makes this an argument in favour of supposing that it is the same race, separated by some mysterious enmity. This argument is, however, not conclusive; for it is quite certain that the two peoples have a little trade together, and that the coast-people are very jealous of this trade. One might, therefore, suppose that these boats were bought from the coast-people; or, that the people at the Galathea Harbour had in them brought their women up to the inland tribe to hide them from the people of the man-of-war. Many a village have I seen where no woman was visible. They were all concealed in the jungle. Admiral Bille also wonders at the rail around the village; but when we take into consideration that there is a wild pig in the forest, and that the people are agriculturists, then the rail appears to me a very natural precaution. The expedition shot birds on its way up the river, and the report of guns drove the people away in such a hurry that they forgot to let the sole inhabitant (a pig) mentioned out of its prison. There is, therefore, no reason to suppose, as Bille hints, that they fled for anybody else. In another paper I hope to lay before the readers of this Magazine a report of another tribe of the Nicobar Islands, and the relation to each other of the different tribes on the islands. After having seen the Shorn-Baeng a second time, we directed our course northwards, but ill-luck followed us steadily. A violent current kept us back; and, sailing and pulling, we only advanced very slowly, and had at last to put in at a village (Ol-en-tji) on the east coast of Little Nicobar. The people of the village were celebrating a feast for the dead, and a number of friends had collected from far and near. Twenty-four big swine had been killed, which fact can give an idea of how great a feast it was. The palm wine (toddy) had circulated freely, and the whole of the assembled crowd were more or less under its influence. We were, however, received very friendly, and were brought into the different huts to see the fun. The huts and the boats on the sand below were decorated with green garlands of palm leaves and flags, among which I noticed a Danish one. In the huts we found the killed pigs, and the women were busy cutting them up. The faces and hands of all the people were smeared with pig's blood, and a confused singing met my ears from every corner, which was unbearable. In the graveyard the wooden monuments had been decorated with gaily-coloured rags, and the ground was covered with palm leaves, and in the centre I noticed a group of women, who distributed betel and toddy to all corners. Around one of the fresh graves the relatives of the deceased were ollected, and they did their best to drive away the evil spirits by beating a cracked gong. The whole affair was more or less a drunken riot, and I was very glad to retreat to a quiet corner in the jungle, where we cooked some fresh eggs; and it was a relief when, towards sunset, the tide turned, and we could proceed on our journey. At parting, following the custom of the place, we fired a couple of guns, and on our way met a couple of big canoes filled with guests desirous of partaking of this savage happiness. At two o'clock in the morning we arrived at our old camping-place on the north coast of Little Nicobar, the men rather knocked up with pulling. Next day we rested in the forenoon; and after a meal, we started on our long journey home. We paid a visit to the Island of Treis, and after firing some shots at the Nicobar pigeons, started, near sunset, for Nancowry. Before leaving we saw, far off, the hills of Katchall and Nancowry just as the setting sun shed light over them. The wind was light and favourable, and we hoped next morning to end our little journey in a pleasant way. At 8 p.m. a black cloud rose on the northern horizon, and grew rapidly; the wind changed, and blew fresh; and after a while, a frightful tropical squall broke over our heads. We had the canoe of our guides in tow; but the cutter laboured heavily, and we soon lost all sight of moon and stars. Drenched to the skin, the men pulled away, and we hoped that in a few hours all our troubles would be ended. Near midnight, however, the skies cleared for a moment, and we caught sight of the moon, but, to our horror, discovered that we were working south- wards instead of northwards. We put the boat about, and again worked away. Towards sunrise the sky cleared again, and, to our joy, we discovered our islands not very far off, and were all delighted, for we were thoroughly drenched, cold, hungry, and miserable. The rain, however, commenced again; the sea rose, and a dense mist surrounded us. Black and white clouds drove past us, and no clue could we anywhere find as to where we were steering. Bitterly did I rue that we had ventured out without a compass. Many thoughts crossed my mind, and I was now prepared to find that we would not reach our destination. At noon, however, we caught sight of the islands, but far off. The sea was high, but the wind having nearly died away, we set to again, pulling for our lives, and after ten hours' hard work, in which I had to take my turn at the oars with the convicts, we at last anchored off our establishment at Nancowry. During the bad weather we had cast adrift the canoe of our guides, at which they were very much displeased. They said that the wicked, powerful sorcerers of the Shom-Baeng had brought this bad weather on us; but I fear it was the monsoon that broke a little earlier than usual, and I leave to the readers to decide for themselves which explanation they will adopt. |

Except for the photographs from 1886, the photographs below are courtesy Dr. S.N.H. Rizvi, The Shompen, Seagull Books, Calcutta 1990.

|

|

A mixed Shompen group, 1886. |

|

|

A Shompen group, 1886. Note the different hair forms present - one possible indication of genetic mixing. |

|

|

A Shompen family outside their hut, 1980s. |

|

|

Shompen woman wearing ornaments (ahav strips of bamboo worn on the ear, geegap armlaces, and naigaak bead necklaces), 1980s. |

|

|

Two Shompen hunters with their weapons and tools, 1980s.

Below:

|

|

|

Firemaking with a fire drill the Shompen way. 1980s. |

|

|

Shompen canoe with outrigger on the Dagmar river. The canoe carries pandanus. |

|

|

Shompen housing ranges from extremely simple huts ... |

|

|

... to villages of raised huts... |

|

|

... to fairly elaborate raised structures. |

|

|

The interior of most Shompen huts remains very similar. |

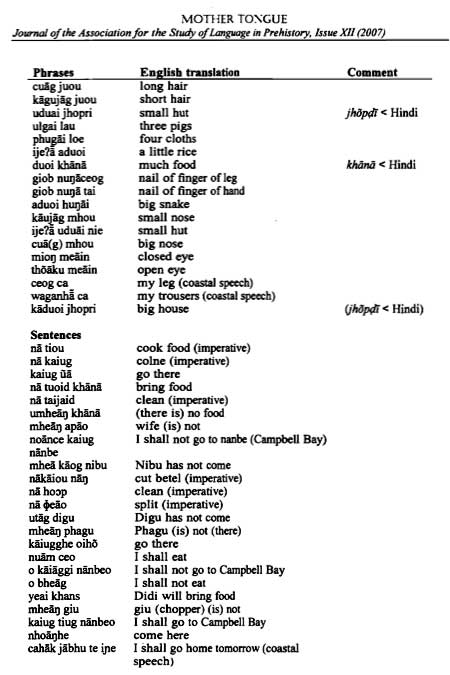

Reprint (with permission): Roger Blench, 2007. "The Language of

the Shompen: a Language Isolate in the Nicobar Islands", Mother

Tongue, 12:179-202

a publication of Harvard University, USA. Roger Blench himself is at

Kay Williamson Educational Foundation, Cambridge, United Kingdom

Read the .JPG files below - or get the PDF file of the article directly from the web

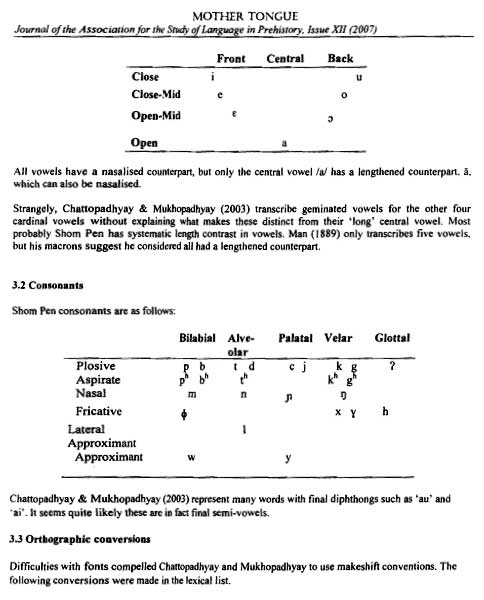

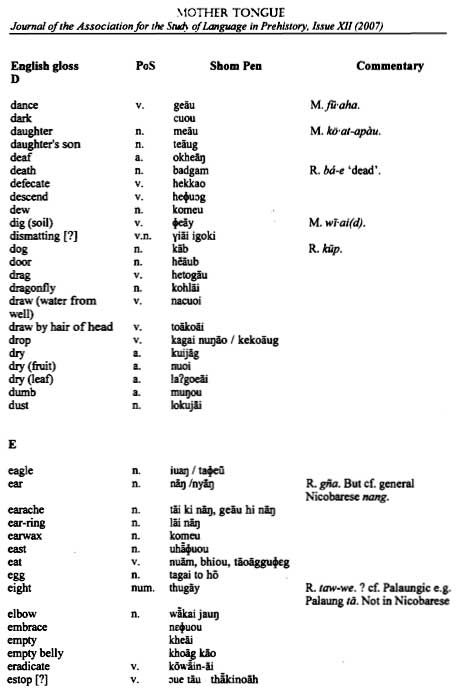

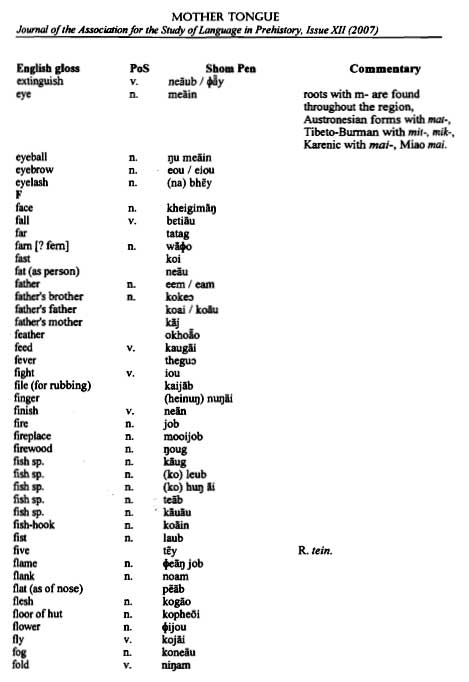

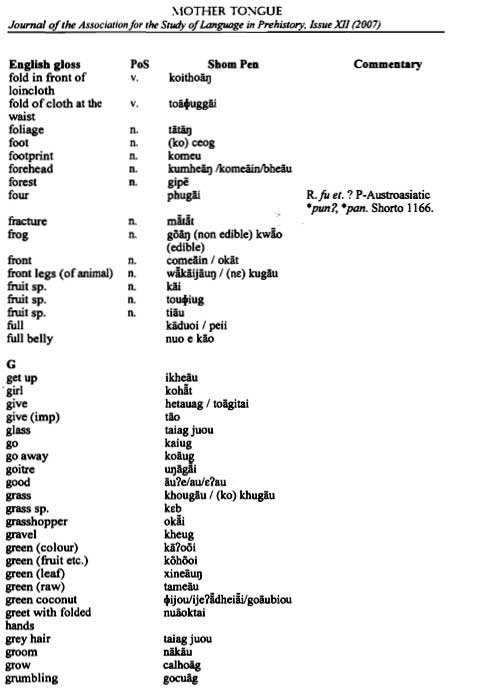

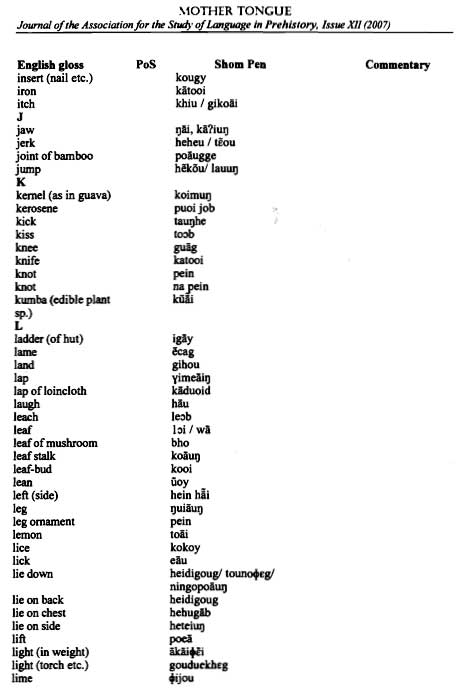

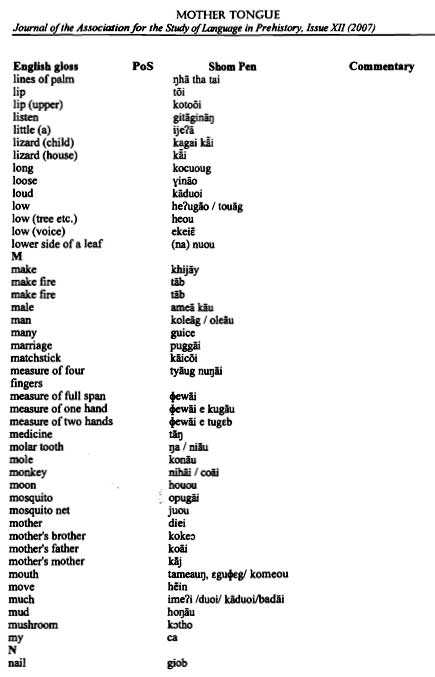

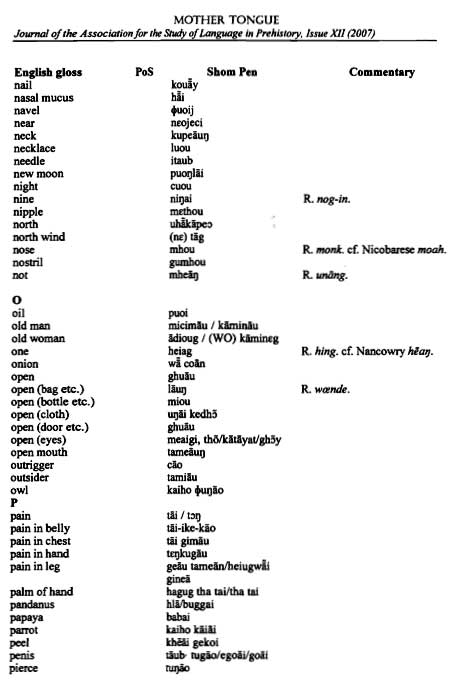

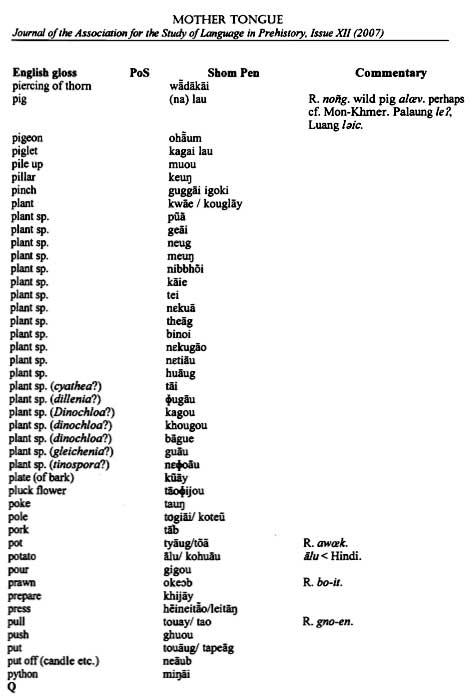

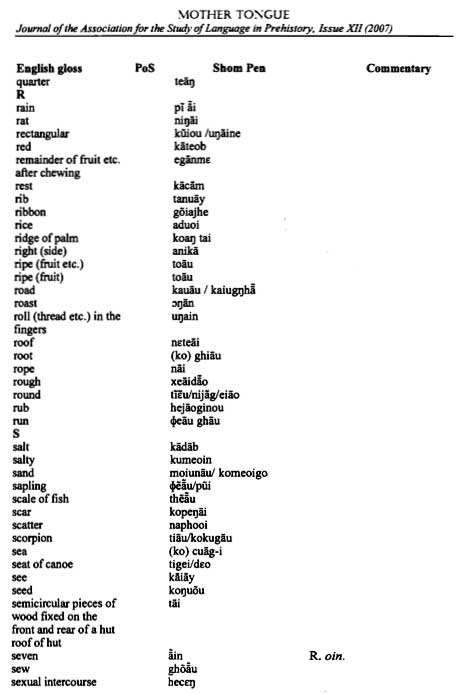

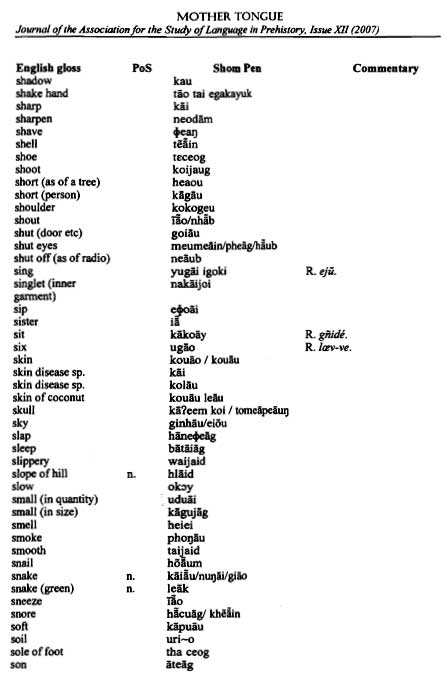

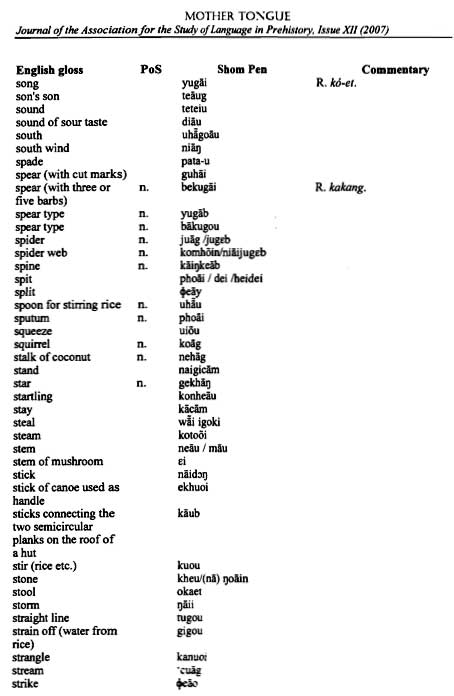

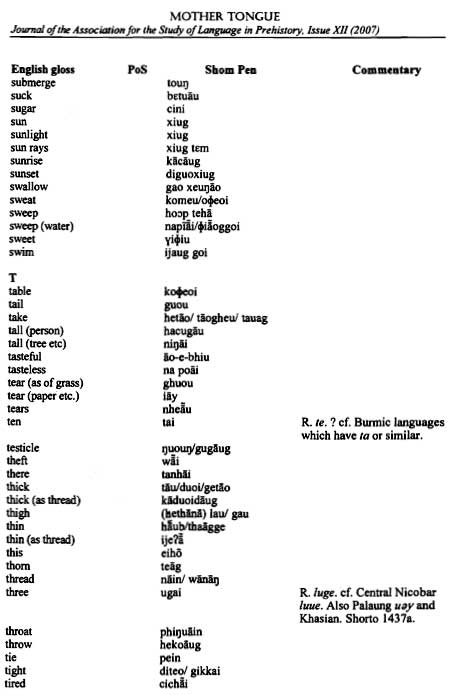

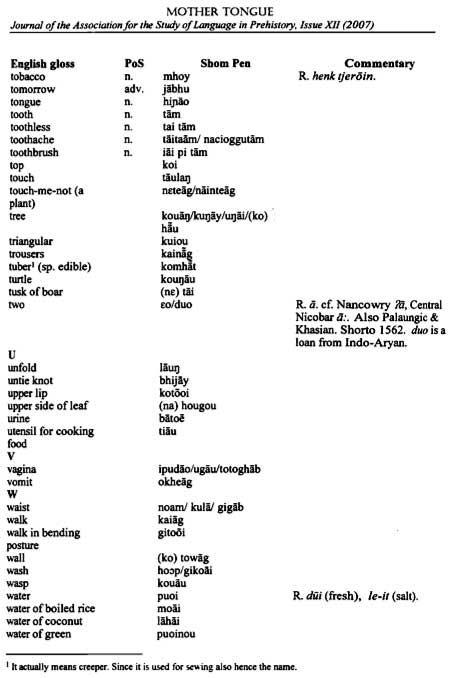

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

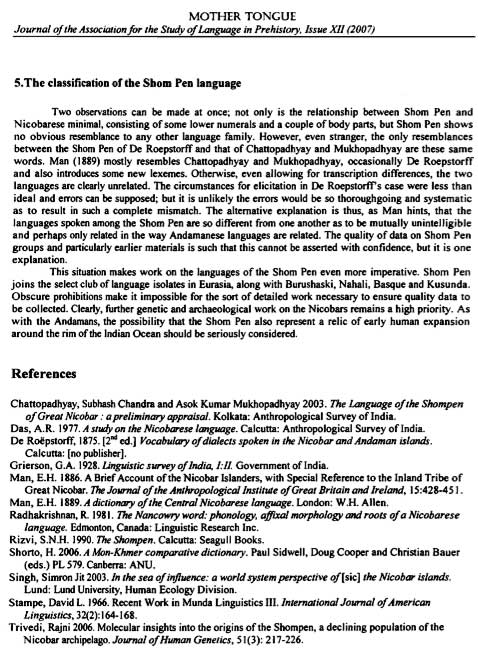

5. Molecular Genetics and possible relationships

The isolation of the Shompen shown on this chart is remarkable: they appear to have been genetically separated from other groups listed even before the Malay populations separated from the Chinese! This puts the Shompen - along with the Andamanese and other Negrito - among the oldest surviving Asian populations!

|

|

Neighbour-joining phylogeny based on autosomal

microsatellite analysis showing the relationship of the

Shompen to Indian, East and Southeast Asian populations. Groups now living in eastern parts of mainland India and

speaking languages of the Austroasian family are: Groups now living in Burma and also speaking languages of

the Austroasian family are:

|

[ Go to HOME

] [ Go to HEAD

OF NICOBAR CHAPTER

]

Last changed 19 July 2008